Beethoven and Berlioz

Sponsored By

- June 6, 2013

- June 7, 2013

Sponsored By

Listen to Audio

Listen to Audio

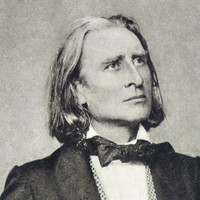

Ferruccio Busoni and Franz Liszt were not only the leading piano virtuosi of their respective eras, but also two of the most inveterate creators of transcriptions. They habitually transformed their own, original compositions, as well as those of other composers, in order to explore fresh sonorities—and to find new audiences and markets for their music. The works catalogues of both Busoni and Liszt contain numerous examples of their delight in tinkering with new sounds and textures. They transcribed piano solos into orchestral works (and vice versa), songs and opera arias into piano solos (and vice versa), and difficult piano solos into super-difficult piano solos.

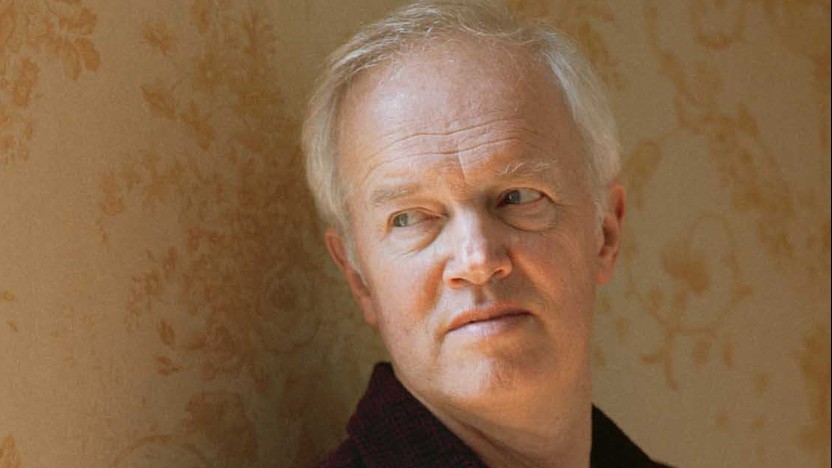

Busoni had strongly held opinions on the subject. In the final analysis, he said, “notation is itself the transcription of an abstract idea. The moment that the pen takes possession of it, the thought loses its original form.” Further, in transcribing a composition from one instrumental voice to another, he maintained that “transcription has become an independent art, no matter whether the starting-point is original or unoriginal. Bach, Beethoven, Liszt, and Brahms were evidently all of the opinion that there is artistic value concealed in a pure transcription, for they all cultivated the art themselves, seriously and lovingly.” That John Adams chose to arrange piano pieces by Liszt and Busoni for The Saint Paul Chamber Orchestra seems only fair play.

Busoni wrote and published the piano Berceuse (Cradle Song) in 1909 and immediately transcribed it for orchestra, naming the new version “Berceuse élégiaque (Des Mannes Wiegenlied am Sarge seiner Mutter)”—the added German subtitle explaining the “elegiac” element, the “cradle song of the man at his mother’s coffin.” Busoni also authorized that the 1909 piano solo be included in a re-issue of an earlier set of piano pieces entitled “Elegien,” thus covering at least three bases in the market for his cradle song. John Adams based his orchestral arrangement on the original piano solo (with its elegiac title).

Sandra Hyslop ©2013

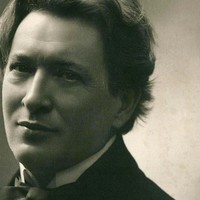

Hector Berlioz earned a living writing music criticism, and his passion for words carried over into his music. In 1839 he created a programmatic symphony based on Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet, and in 1840 he made another nod to “the Bard” with his song collection Les Nuits d’été (Nights of Summer), the title referencing A Midsummer Night’s Dream, which Berlioz knew as “Le Songe d’une nuit d’été.” Using poems from an 1838 volume by his friend and fellow critic Théophile Gautier, Berlioz completed the cycle for voice and piano in 1841.

Berlioz orchestrated one song from Les Nuits d’été in 1843, and then he completed the set and prepared it for publication in 1856. (He did not hear the full orchestra version performed in his lifetime.) The first song, Villanelle, announces the coming of spring in music propelled by a bright and pulsing accompaniment. The Spectre of the Rose infuses a dead flower with romance and longing, while On the Lagoons brings the rocking lilt of the sea to a heartbreaking song of mourning. Absence is another meditation on loss and distance, albeit one with a glimmer of hopefulness in its central ascending motive. At the Cemetery, Moonlight contains a verse describing a dove singing in a cemetery, words that could justly describe Berlioz’s melody: “An air sickly tender, / At the same time charming and ominous, / Which makes you feel agony / Yet which you wish to hear always; / An air like a sigh from the heavens / of a love-lorn angel.” That delectable agony dissipates for the swashbuckling final song, Unknown Island.

Aaron Grad ©2012

Listen to Audio

Listen to Audio

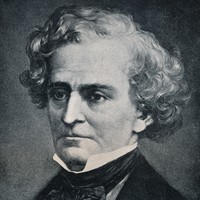

Franz Liszt was known to revise and re-work his compositions multiple times, sometimes over a long span of years. In the case of La lugubre gondola (The black gondola), he composed three versions, all beginning in 1882. Version I was a piano solo. Late in the year he undertook a transcription of La lugubre gondola as a duet for cello or violin and piano; in turn, he transformed that version of the piece into a piano solo, completing it in January 1883 as La lugubre gondola II. This is the version upon which John Adams based his arrangement for the SPCO, giving it the English title The Black Gondola.

It remains to be noted that Liszt’s Black Gondola has become permanently linked with the death of Richard Wagner, the husband of Liszt’s daughter Cosima. In 1882 Liszt had composed La lugubre gondola in response to the striking visions of funeral gondolas on the lagoons of Venice. His revered son-in-law was carried to his final resting place in just such a procession in February 1883, not two months after Liszt composed this music.

Sandra Hyslop ©2013

Listen to Audio

Listen to Audio

(Duration: 34 min)

With his First Symphony, composed in 1800, the ambitious young Ludwig van Beethoven proved that he could rival his onetime teacher, Franz Joseph Haydn, in his signature genre. Two years later, Beethoven went a step farther, using Haydn’s template as a platform for a Second Symphony that was even bolder and more extreme. The backdrop for this pivotal symphony was a terrible change that was overtaking Beethoven in 1802, when his hearing loss progressed to the point that he could no longer hide it. He finished Symphony No. 2 while convalescing in Heiligenstadt, outside of Vienna, where he suffered in a nearly suicidal state of agony, as we know from an unsent letter to his brothers, found among his papers after his death.

Borrowing a feature found in most of Haydn’s iconic London symphonies, Beethoven’s Second Symphony begins with a meaty introduction full of shifting rhythms, moody harmonies and jarring accents. The fast body of the first movement enters, conversely, with just a wisp of melody in the lower strings. Whereas Haydn loved the elegant dichotomy of forte and piano intensities, Beethoven’s score heightens the contrast, calling for even louder fortissimo and even softer pianissimo dynamics.

The Larghetto slow movement contrasts the adventurous opening movement with music that is serene, tuneful and unabashedly beautiful. The melodic phrases introduced by the violins and answered by the clarinets stay within the sweet treble range of female singers, emphasizing the modest, songlike quality of the material.

The third movement brings Beethoven’s inaugural symphonic scherzo (Italian for “joke”), his raucous answer to Haydn’s genial minuets. The running joke here is an echoing pattern in which the last repetition is shockingly robust.

In the finale, a somewhat rough and rude main theme provides much of the comedic fodder. Beethoven’s craftiness is especially evident in the playful ways he works back to that snarling motive.

Aaron Grad ©2023

Saturday's performance will be broadcast live on Classical Minnesota Public Radio stations.

Get driving directions and find nearby parking.

Find dining options close to the venue.

View seating charts to find out where you'll be seating.

SPCO concerts are made possible by audience contributions.

For exclusive discounts, behind-the-scenes info, and more:

Sign up for our email club!