Dawn Upshaw Returns

Sponsored By

- October 26, 2013

Sponsored By

Mozart began composing symphonies at the age of eight, and his earliest examples read like postcards from his relentless tours: he penned his first in London, added more in Paris and Vienna, and buckled down on the form while in Rome and Milan. When his itinerant career as a child prodigy came to a halt at the end of 1771, the 15-year-old Mozart, back in his provincial hometown of Salzburg, began composing at a ferocious rate, including eight symphonies in as many months.

While Mozart was developing as a composer, the symphony itself was still in a state of infancy. Growing out of the Italian overture or sinfonia, traditionally in three sections organized fast-slow-fast, the symphony assumed its familiar dimensions with the insertion of a third-movement minuet, a style borrowed from French dance suites. The composer most closely associated with the development of the symphony was Joseph Haydn, and by the early 1770s he was past his fiftieth symphony. Mozart did not have the benefit of direct contact with Haydn until later in Vienna, but he did enjoy close proximity to Joseph’s younger brother Michael Haydn, the Salzburg Konzertmeister and a fine composer of symphonies himself.

The Symphony No. 20 is in the bright key of D major, with a pair of trumpets included to reinforce the brilliant tone. The opening Allegro movement grants the winds unusual prominence, and even the trumpets join in on leaping melodic figures that were compatible with the valveless instruments from Mozart’s time. The Andante, a charming rumination on rising and falling triplet motives, introduces a new tone color in the form of a flute, while the rest of the winds sit out. (The small orchestra in Salzburg would have had oboists who could double on flute when needed.)

The Minuet is a robust example of that French dance style, set in three moderate beats per measure. The contrasting trio section shifts the mood with a key change, pulsing pedal tones, and smooth slurs in the strings. The finale once again entrusts the winds with important thematic material, this time a repeated-note figure that answers the scampering melody brought out by the strings.

Aaron Grad ©

The Cold Pane is about the opposition between the natural, external world and the human, internal world of emotions, and how these two worlds can be at odds. It’s also about life, death, grief, and the seasons. The cycle explores how we seek meaning in the events of the natural world, and it questions whether the meaning we find there is actually present, or something we impose in our desire to find meaning there.

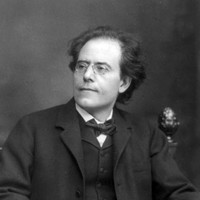

The Cold Pane sets five poems by the esteemed Kentucky author, farmer, activist, and scholar Wendell Berry. The cycle alternates between poems that describe the natural world, and, particularly, the seasons, and poems that describe the human, emotional world of grief. This opposition between external and internal worlds carries with it several other related oppositions—cyclical versus linear time, light versus darkness, life versus death, and objectivity versus subjectivity. In order to reflect these oppositions, I composed the songs dealing with the natural world according to more-or-less strict processes—systems that, once set in motion, operate according to their own internal logic, without adjustment or interference on my part. In contrast, for the songs dealing with the internal, emotional world—“The Cold Pane,” and “The Widower”—I wrote in a much more intuitive, spontaneous, and traditionally lyrical mode. “The Widower,” on a personal level, describes the experience my father had after my mother passed away, and it was with this poem that I began to build a cycle. The work’s tonal structure also reflects the oppositions embedded in the song texts through an oscillation between the two tonal centers of G-sharp minor and A major. This tonal relationship intentionally references the similar harmonic plan of Mahler’s Fifth Symphony—a piece that has a very special place in my heart.

This piece’s unusual instrumentation grew out of two desires: first, to create an ensemble in which all the performers could stand; and second, to reference, but not explicitly duplicate, the instrumentation of the bluegrass band—a sound world and singing style that has been a major source of inspiration for me. Previous works of mine have drawn inspiration from certain folk singing traditions from Kentucky—particularly, Appalachian ballad singing and Old Regular Baptist hymnody. The influence of these traditions is less prevalent here, though the folk-wisdom quality of the words for Berry’s “The Cold Pane” did invite hymn-like sounds into the piece, albeit briefly. In any case, this piece continues my investigation into the people, places, and cultural practices of my home state.

Finally, I would like to say what an immense honor it was for me to write this piece for Dawn Upshaw and The Saint Paul Chamber Orchestra. I am incredibly blessed to have had the opportunity to work with such talented, passionate musicians.

Shawn Jaeger ©2013

Listen to Audio

Listen to Audio

While working full-time as a teaching assistant, taking compositions lessons twice a week, and playing viola in a student orchestra, the 17-year-old Franz Schubert managed to write new music at an astonishing rate that averaged at least 65 measures of music every single day. His efforts that year included his Symphony No. 2, which at most might have received a reading from a student orchestra. Not a note of his music had reached the public yet, and during his entire short life he never managed to secure a single performance of any symphony.

As a student composer in Vienna, Schubert could not help but be engulfed by the towering achievements of Haydn, Mozart and Beethoven (who had by then debuted eight of his nine symphonies). Like Beethoven before him, Schubert used the instrumentation and general outline of Haydn’s final London symphonies as a point of entry. In Schubert’s Symphony No. 2, the instrumentation, slow introduction and the use of a minuet third movement instead of a Beethovenian scherzo all point to Haydn’s influence. One particular trick found all over Haydn’s symphonies comes in the Allegro vivace body of Schubert’s first movement, when the main theme enters in the strings at a pianissimo dynamic before being repeated fortissimo by the full orchestra.

The Andante second movement takes the form of a theme and variations, with a simple and song-like theme that adds a playful extra measure in its second half. The climactic fourth variation moves to C minor, which returns as the surprising key center for the Menuetto. Before the finale launches, four introductory measures bridge the harmonic distance back to the home key of B-flat major. Then, like horses on the hunt, the orchestra gallops off at a Presto tempo.

— © Aaron Grad

Aaron Grad ©2016

Gustav Mahler had a special affection for the collection of German folk poetry titled Des Knaben Wunderhorn, or The Youth’s Magic Horn. His first Wunderhorn settings, composed from 1887 to 1890, comprised nine songs for voice and piano. He followed with a set of twelve more songs for voice and orchestra, originally published under the title Humoresques in 1899. Meanwhile, he incorporated some of the same songs into his Second, Third, and Fourth Symphonies.

The oboist and chamber music professor Philip West created chamber ensemble arrangements of several of these Wunderhorn songs for his wife, the mezzo-soprano Jan DeGaetani, who recorded the set in her very last session before succumbing to leukemia in 1989. (Dawn Upshaw, incidentally, was once a student of DeGaetani, and her frequent recital partner, Gilbert Kalish, was DeGaetani’s accompanist for thirty years.)

Wer hat dies Liedlein erdacht? (Who Thought Up this Pretty Little Song?) tells of a girl pining for her beau, and a “pretty little song…brought over the water by three geese,” a melody that takes flight in the final measures. Verlor’ne Müh (Lost Effort) follows as a dialogue between a girl and a boy; she offers to go out to check the lambs with him, offers him a bite to eat, and even offers her heart, but he wants none of it!

Wo die schönen Trompeten blasen (Where the Beautiful Trumpets Blow) is a bittersweet song of a soldier leaving his beloved as he heads to war, as signaled by the fanfare figures at the end. From the most serious of the Wunderhorn songs, this set progresses to the silliest, Lob des hohen Verstandes (In Praise of Higher Understanding) in which a donkey judges a singing contest between a cuckoo and a nightingale.

Aaron Grad ©

Composer Shawn Jaeger and soprano Dawn Upshaw, featured on this program, will join us for a Composer Conversation at Amsterdam Bar and Hall in Saint Paul on Wednesday, October 23 at 7:00pm. Composer Conversation Series events are FREE but reservations are required. More at thespco.org/composer-conversation-series.

Get driving directions and find nearby parking.

Find dining options close to the venue.

View seating charts to find out where you'll be seating.

Get driving directions and find nearby parking.

Find dining options close to the venue.

View seating charts to find out where you'll be seating.