Dawn Upshaw Sings Ravel

Sponsored By

- May 30, 2013

- May 31, 2013

- June 1, 2013

Sponsored By

Listen to Audio

Listen to Audio

The Morning Symphony opens with a slow introduction. The first violins enter alone, then the second violins join in harmony and soon the entire orchestra surges to a bright climax, like a sunrise breaking over the horizon. The fast body of the movement begins with a melody played by flute alone, the first of many solo passages that show this symphony to be a descendent of the concerto grosso (a collective concerto for multiple soloists and orchestra) as much as it is an offspring of the operatic sinfonia or overture.

The slow movement, scored without winds, emphasizes solo parts for violin and cello. Instead of continuing to the fast finale in the manner of a three-part Italian sinfonia, Haydn borrowed from the French dance suite and inserted a Menuet, a court dance marked by its stately pulse of three beats per measure. Through Haydn’s influence, the minuet (and later, in Beethoven’s adaptation, the scherzo) became an indispensable component of a symphony. Even in this very early example of symphonic form, the finale displays Haydn’s typical panache, like how he turns a simple melodic gesture of a rising scale into a pervasive, energizing accompaniment figure.

Aaron Grad ©2018

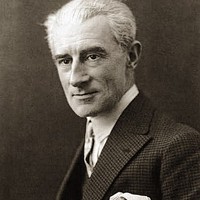

In 1925, the American patron Elizabeth Sprague Coolidge commissioned a new work from Maurice Ravel, the leading French composer of the day. Coolidge specified the genre (song cycle) and instrumentation (female voice with flute, cello and piano), and left the choice of text to Ravel, who selected poems from an eighteenth-century volume he had recently read. The resulting piece, Chansons madécasses, is one of a legendary list of compositions Coolidge initiated, including Bartók’s String Quartet No. 5, Stravinsky’s Apollo, and Copland’s Appalachian Spring.

Ravel culled the texts from a 1787 collection by Evariste Désiré de Forges Parny, who was most famous for an earlier book of erotic poems. Parny had claimed that his Madagascar Songs were actual folk verses from the African island, but more likely the poems were entirely of his own invention, at most influenced by his proximity to Madagascar when he worked for France’s colonial army in India. The texts are unabashedly lustful (“Your caresses burn all my senses / Stop or I will die!”) and political (“Do not trust the white men!”), surprising choices for the generally asexual and cool-headed composer. Ravel must have responded to the exotic nature of the material, part of the same fascination he exploited in Shéhérazade, Tzigane (Gypsy), and even the Blues movement of his Violin Sonata.

The opening song, “Nahandove,” uses the bare texture of cello and voice to capture the longing at the beginning and end of the poem. Ravel's text setting obsesses over the name “Nahandove,” amplifying the intense passion and romance of the raciest lines of the text. “Aoua!” does not shy away from the brutal intensity of the opening shout or the darkness of colonial oppression, building thick textures and crunching dissonances. The final song, “Il est doux,” captures the sweet indolence of a summer day, with girls singing and birds in the rice field. The text again veers toward the erotic, and Ravel matches it with slow and sensuous dance music. The singer breaks the spell with a nonchalant final line: “Go and prepare the meal.”

Aaron Grad ©

Night of the Four Moons, commissioned by the Philadelphia Chamber Players, was composed during the Apollo 11 flight [July 1969]. The work is scored for alto (or mezzo-soprano), alto flute (doubling piccolo), banjo, electric cello, and percussion. The percussion includes Tibetan prayer stones, Japanese Kabuki blocks, alto African thumb piano (mbira), and Chinese temple gong in addition to the more usual vibraphone, crotales, tambourine, bongo drums, suspended cymbal and tamtam. The singer is also required to play finger cymbals, castanets, glockenspiel and tamtam.

I suppose that Night of the Four Moons is really an "occasional" work, since its inception was an artistic response to an external event. The texts—extracts—drawn from the poems of Federico García Lorca—symbolize my own rather ambivalent feelings vis-à-vis Apollo 11. The texts of the third and fourth songs seemed strikingly prophetic!

The first three songs, with their brief texts, are, in a sense, merely introductory to the dramatically sustained final song. The moon is dead, dead ... is primarily an instrumental piece in a primitive rhythmical style, with the Spanish words stated almost parenthetically by the singer. The conclusion of the text is whispered by the flutist over the mouthpiece of his instrument. When the moon rises ... (marked in the score: "languidly, with a sense of loneliness") contains delicate passages for the prayer stones and the banjo (played "in bottleneck style", i.e., with a glass rod). The vocal phrases are quoted literally from my earlier (1963) Night Music I (which contains a complete setting of this poem). Another obscure Adam dreams ... ("hesitantly, with a sense of mystery") is a fabric of fragile instrumental timbre, with the text set like an incantation.

The concluding poem (inspired by an ancient Gypsy legend)—Run away moon, moon, moon!— provides the climactic moment of the cycle. The opening stanza of the poem requires the singer to differentiate between the "shrill, metallic" voice of the Child and the "coquettish, sensual" voice of the Moon. At a point marked by a sustained cello harmonic and theclattering of Kabui blocks (Drumming the plain,/the horseman was coming near…), the performers (excepting the cellist) slowly walk off stage while singing or playing their “farewell” phrases. As they exit, they strike an antique cymbal, which reverberates in unison with the cello harmonic. The epiloque of the song (Through the sky goes the moon / holding a child by the hand) was conceived as a simultaneity of two musics: "Musica Mundana" ("Music of the Spheres"), played by the onstage cellist, and "Musica Humana" ("Music of Mankind"), performed offstage by singer, alto flute, banjo, and vibraphone. The offstage music (“Berceuse, in stile Mahleriano”) is to emerge and fade like a distant radio signal. The F-sharp major tonality of the “Musica Humana” and the theatrical gesture of the preceding processionals recall the concluding pages of Haydn’s “Farewell” Symphony.

George Crumb ©

A year after Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart married Constanze Weber without his father’s blessing, the young couple left for Salzburg in the hope of smoothing the family tension. On their return trip to Vienna several months later, they stopped in Linz, where their host, Count Johann Joseph Anton von Thun-Hohenstein, arranged for the court orchestra to perform a concert. Mozart wrote to his father, “I really cannot tell you what kindnesses the family are showering on us. On Tuesday, November 4, I am giving a concert in the theater here and, as I have not a single symphony with me, I am writing a new one at breakneck speed, which must be finished by that time.” It was breakneck speed indeed, for Mozart only arrived on October 30, leaving him less than five days to compose the new piece, copy out the parts, and rehearse with the orchestra.

Mozart’s Symphony No. 36 in C Major, nicknamed “Linz” for its city of origin, betrays no evidence of strained composition. In fact, it is rare among Mozart’s symphonies in that it begins with a leisurely introduction. The opening harmonies wander away from C-major and settle in C-minor, creating a moody counterpoint to the generally bright disposition of the symphony. Further excursions into minor keys, in the first movement’s secondary theme and later in the graceful Andante, echo the tonal rub of the introduction. After a playful Menuetto, the Presto finale sprints through a fluid range of themes, with short motives bouncing among sections. There is a family resemblance between this finale and another C-major movement that is among Mozart’s most famous, the contrapuntal closing of the Symphony No. 41 (“Jupiter”).

Aaron Grad ©2022

Get driving directions and find nearby parking.

Find dining options close to the venue.

View seating charts to find out where you'll be seating.

Get driving directions and find nearby parking.

Find dining options close to the venue.

View seating charts to find out where you'll be seating.