Haydn's Second Cello Concerto

Listen to Audio

Listen to Audio

In 1939, Igor Stravinsky suffered what he called “the most tragic year of my life.” His daughter, wife and mother all died within months of each other, and the outbreak of World War II sent him into exile for the second time, from his adopted home in Paris to the United States. He married his longtime mistress Vera in 1940, and together they started a new life in West Hollywood in 1941. Stravinsky soon accepted a commission from a local conductor, Werner Janssen, and began what would be his first major work composed entirely in the United States, Danses concertantes.

The musical language of Danses concertantes is typical of Stravinsky’s neoclassical style, full of quick character changes, crisp rhythms, bone-dry textures and tight harmonies. With its small orchestra and ample instrumental solos, Danses concertantes exhibits a kinship to the Dumbarton Oaks Concerto from 1938; the two works have been called Stravinsky’s Brandenburgs, after Johann Sebastian Bach’s famous set of mixed-ensemble concertos. Even though Stravinsky designed Danses concertantes for the concert stage, it did not take long for its inherent dance sensibility to be recognized. Stravinsky’s friend and longtime collaborator George Balanchine was the first to choreograph the work when he created a version in 1944 for the Ballet Russe de Monte Carlo, a successor to Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes.

Danses concertantes begins with an introductory March, its steady meter obscured by shifting layers and displaced accents. The only extended solo in this preparatory movement is for the leader of the six-member violin section. The second movement is a Pas d’action, borrowing a term from ballet for an ensemble dance. The third movement, taking the form of a theme and variations, is the longest and most abstracted of the work. The thematic section is tender and diffuse, and the playful variations and shuffling coda bear little surface resemblance to the theme. The Pas de deux borrows another dance convention: a dance for two, often for the romantic leads. Here, the oboe and clarinet take the spotlight, their duet surrounded by other reveries. The concluding March revisits the opening music.

Aaron Grad ©2025

Listen to Audio

Listen to Audio

In 1766, Prince Nikolaus Esterházy completed a sumptuous summer palace, Eszterháza, on the site of a former hunting lodge. The “summers” he and his entourage spent in the country eventually lengthened to ten months of each year, and the prince expected his Kapellmeister, Franz Joseph Haydn, to keep him well supplied with musical diversions. The composer acknowledged the impact of this obligation, once writing, “In Eszterháza I was forced to become original.”

Haydn’s Cello Concerto in D Major was a product of that fruitful environment. Prepared in 1783, it featured the talents of Anton Kraft, principal cellist of the Esterházy court orchestra from 1778 to 1790. Kraft studied composition with Haydn, and scholars long believed that the cellist had composed the concerto himself, until a signed autograph copy discovered in 1951 confirmed the music as Haydn’s. The solo part is far more demanding than Haydn’s other surviving Cello Concerto, from the 1760s, so we can presume that Haydn factored in Kraft’s abilities and perhaps consulted directly with him.

The Allegro moderato first movement begins with a relaxed exposition for the orchestra. When the cello enters with the melody, the violins harmonize from below; for the second main theme, the violins again join the cello, this time with an upper harmony. These harmonized melodies come straight from the realm of opera, the genre that occupied most of Haydn’s time in that period. In this concerto, the solo cello makes the most of its wide range to play all the roles, from the profound bass to the coquettish soprano.

The Adagio is an intimate rondo, its stately music coaxed along by quick notes in the accompaniment. For the first statement of the theme, and again in one of its returns, only violins and violas accompany the solo cello, imparting a special delicacy to the texture. As in the first movement, the finale begins at a gentle piano dynamic, withholding the impact of a forte arrival. Haydn’s legendary humor animates this movement, with breath-catching holds between phrases, extreme changes in range, and an unexpected detour into the minor mode.

Aaron Grad ©2024

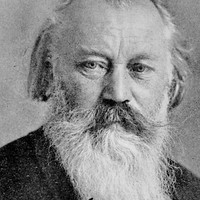

At the age of 57, Brahms declared his retirement from composition, intending his Second String Quintet from 1890 to be his final work. Eventually an encounter with a clarinetist coaxed Brahms back to composing — twice actually, since he “retired” again in 1894 — so the quintet turned out not to be his swan song after all. In both the first quintet from 1882 and this successor, Brahms used Mozart’s configuration with a second viola, as opposed to the second cello found in quintets by Boccherini and Schubert. (Brahms had drafted a two-cello quintet back in 1862, but after his friend Joseph Joachim expressed misgivings about the scoring, Brahms converted it into a piano quintet.)

Adapting a sketch drafted for an unrealized fifth symphony, Brahms assigned the quintet’s heroic first theme to the cello. The two violas come to the fore in the contrasting theme, their harmonies gliding together as smoothly as two dancers in a Viennese ballroom. The Adagio also links the two violas over pizzicato cello, with a stately pace and dotted rhythms that hint at a bygone Baroque sensibility. For the finale, a viola introduces a compact motive that moves through a variety of keys, speeds and orchestrations until it climaxes in an accelerated tempo. It is intriguing to imagine these final bursts of ecstatic music as an intentional goodbye, supposing Brahms had stuck with his planned retirement.

Aaron Grad ©2020

Please note: This program has changed from what was originally published. Thomas Zehetmair has withdrawn from his upcoming concerts with the SPCO due to medical concerns which are preventing him from travel. He sends his sincerest regrets, and we look forward to welcoming him back next season when he has fully recovered. Zehetmair's absence necessitates a change to this week's repertoire, and the new program will now be led by SPCO musicians.

Tickets printed for Purcell, Britten and Shostakovich are still valid for this week's performances. You may use your original tickets regardless of the printed concert title, as long as the printed date is correct.

Get driving directions and find nearby parking.

Find dining options close to the venue.

View seating charts to find out where you'll be seating.

Get driving directions and find nearby parking.

Find dining options close to the venue.

View seating charts to find out where you'll be seating.