Schubert’s Fifth Symphony

Sponsored By

- October 4, 2013

Sponsored By

Listen to Audio

Listen to Audio

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart delighted his fans in Vienna by introducing a dozen new piano concertos between 1784 and 1786, and he might have kept up that pace if a war with the Ottoman Empire hadn’t scattered the aristocrats who subscribed to those concerts. He entered the Piano Concerto No. 23 in A Major into his catalog of completed compositions on March 2, 1786, and he probably debuted it on one of the three programs he presented that spring.

Preliminary sketches, which may date from as early as 1784, included a pair of oboes in the instrumentation, but the final version substituted clarinets instead. The concerto’s first movement gives the woodwinds far more attention than they would have been accustomed to at that time, starting with unaccompanied phrases in the orchestra’s introductory tutti and continuing in the conversational development section.

Later editions notched the tempo of the middle movement up to Andante, but Mozart’s manuscript for this heavy-hearted movement clearly calls for the slower and more affecting Adagio tempo. Again the woodwinds play an outsized role in accompanying and answering the piano, and they also introduce the only wholly cheerful passage in the movement, in the contrasting major key. Minor-key episodes within the rondo finale rehash some of the angst of the slow movement, but the main recurring theme always reaffirms the jovial home key with its definitive leaps.

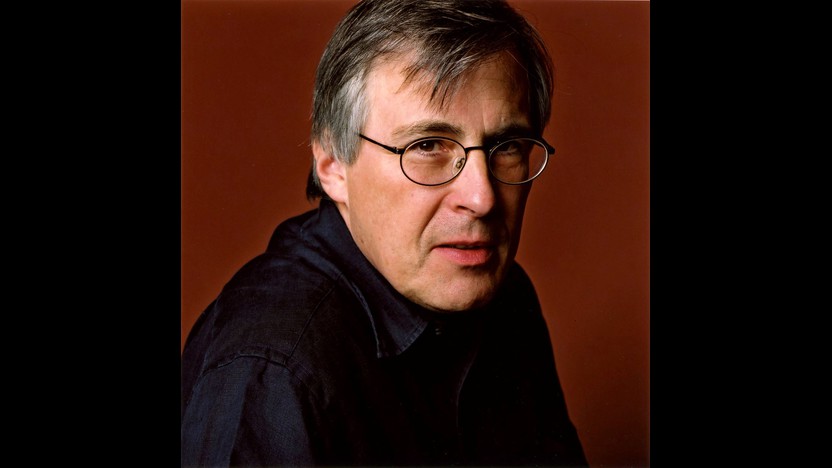

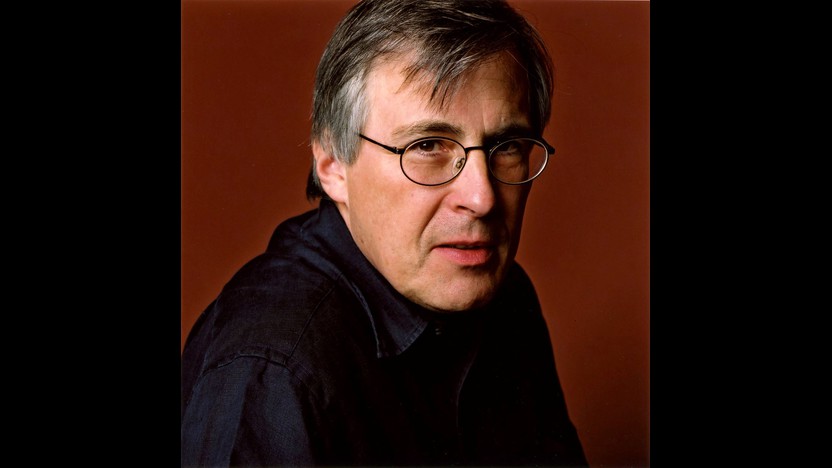

Aaron Grad ©2024

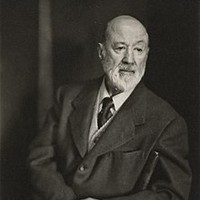

Charles Ives, who trained as a composer at Yale, resigned from his post as a church organist in 1902 and embraced the professional path of an insurance man. In the following decades he amassed a fortune, composed on evenings and weekends, and developed a singular body of music, much of which spent decades on shelves before finally reaching the public.

Some of the material included in Three Places in New England may have originated as early as 1903. Ives developed the work as a set of three movements, each based on a particular location, and he completed a version for full orchestra in 1914. The score languished for fifteen years, by which point Ives had come to the attention of Henry Cowell, a younger American composer sympathetic to Ives’s maverick tendencies. Cowell persuaded the conductor Nicolas Slonimsky, head of the Boston Chamber Orchestra, to program something by the unknown “amateur” composer from Danbury, Connecticut. Upon Slonimsky’s invitation, Ives undertook a revision of Three Places in New England in 1929, reducing the instrumentation to a chamber orchestra and condensing some of the musical ideas. Slonimsky conducted the first public performance in 1931, at a concert in New York’s Town Hall financed by Ives himself.

Ives titled the first movement The “St. Gaudens” in Boston Common (Col. Shaw and his Colored Regiment), a reference to the monument by Augustus Saint-Gaudens in Boston’s oldest park. The bronze relief sculpture depicts Colonel Robert Gould Shaw on horseback, leading the Massachusetts 54th Regiment—the first African-American regiment in the Union army, which suffered heavy losses (including the death of Shaw) while fighting near Charleston, South Carolina, in 1863. In the score, Ives prefaced the movement with a verse that he wrote:

<div style="margin-left: 1em;"> Moving—Marching—Faces of Souls!<br> Marked with generations of pain,<br> Part-freers of a Destiny,<br> Slowly, restlessly—swaying us on with you<br> Towards other Freedom!<br> The man on horseback, carved from<br> A native quarry of the world Liberty<br> And from what your country has made.<br> You images of a Divine Law<br> Carved in the shadow of a saddened heart—<br> Never light abandoned—<br> Of an age and of a nation.<br> Above and beyond that compelling mass<br> Rises the drum-beat of the common-heart<br> In the silence of a strange and<br> Sounding afterglow<br> Moving—Marching—Faces of Souls!<br> </div><br>

After the hushed reverence of the first movement, the second barrels forth with all the raucous energy of a country marching band, not unlike those led by Ives’s father decades earlier in Danbury. (This music is in fact derived from an earlier composition titled Country Band March.) Putnam’s Camp, Redding, Connecticut pays tribute to the site of a Revolutionary War encampment set up by General Israel Putnam, and it showcases Ives’s penchant for collage-like quotations from well-known tunes, including “Yankee Doodle” and “The Star-Spangled Banner.” Ives supplied a detailed program for this movement:

<div style="margin-left: 1em;">Once upon a ‘4 July,’ some time ago, so the story goes, a child went here on a picnic, held under the auspices of the first Church and the Village Cornet Band. Wandering away from the rest of the children past the camp ground into the woods, he hopes to catch a glimpse of some of the old soldiers. As he rests on the hillside of laurels and hickories the tunes of the band and the songs of the children grow fainter and fainter;—when— ‘mirabile dictu’—over the trees on the crest of the hill he sees a tall woman standing. She reminds him of a picture he has of the Goddess Liberty,—but the face is sorrowful—she is pleading with the soldiers not to forget their ‘cause’ and the great sacrifices they have made for it. But they march out of camp with fife and drum to a popular tune of the day. Suddenly, a new national note is heard. Putnam is coming over the hills from the center,—the soldiers turn back and cheer. The little boy awakes, he hears the children's songs and runs down past the monument to ‘listen to the band’ and join in the games and dances.</div><br>

The third movement, The Housatonic at Stockbridge, was inspired by a walk Ives took with his wife, Harmony, on their honeymoon in the Berkshires in 1908. Ives borrowed the movement title from a poem by Robert Underwood Johnson, and he included these excerpts from Johnson’s text as an epigraph:

<div style="margin-left: 1em;"> Contented river! In thy dreamy realm—<br> The cloudy willow and the plumy elm . . . <br> Thou hast grown human laboring with men <br> At wheel and spindle; sorrow doest thou ken; . . . <br> Thou beautiful! From every dream hill <br> What eye but wanders with thee at thy will, <br> Imagining thy silver course unseen <br> Conveyed by two attendant streams of green. . . <br> Contented river! And yet over-shy <br> To mask thy beauty from the eager eye; <br> Hast thou a thought to hide from field and town? <br> In some deep current of the sunlit brown <br> Art thou disquieted—still uncontent <br> With praise from thy Homeric bard, who lent <br> The world the placidness thou gavest him? <br> Thee Bryant loved when life was at its brim; . . . <br> Ah! There's a restive ripple, and the swift <br> Red leaves—September's firstlings—faster drift; <br> Wouldst thou away, dear stream? Come, whisper near! <br> I also of such resting have a fear; <br> Let me tomorrow thy companion be, <br> By fall and shallow to the adventurous sea! <br><br>

Aaron Grad ©2013

Watch Video

Watch Video

Schubert enjoyed a childhood rich with music—singing in the court choir, playing string quartets with his family, and participating in the school orchestra—but he only began composing around the age of twelve or thirteen. Like his father and brothers, he trained as a teacher, and at seventeen he began working as a teaching assistant at an elite Viennese school, while also keeping up twice-weekly composition lessons with the local Kapellmeister, Antonio Salieri.

Schubert’s accomplishments in the next two years must rank as the greatest growth spurt in musical history: he composed some 300 songs, plus four symphonies, three masses, five musical dramas, three string quartets, three violin sonatas and dozens of other works. This flurry all came before Schubert reached his twentieth birthday, while he was working full-time, and before the Viennese public had seen or heard a single note of his music.

HAYDN-ERA ORCHESTRATION Schubert completed the Symphony in B-flat Major on October 3, 1816. Aside from a private reading that fall, the symphony sat dormant until long after his death; the first public performance came in 1841, and the score was not published until 1885. Of all of Schubert’s symphonies, finished and unfinished, this is the only one that omits clarinets, trumpets and timpani from the orchestration, essentially turning back the clock to the symphonic customs of the 1780s. (Haydn composed 15 symphonies between 1781 and 1786 with instrumentation identical to Schubert’s, while Mozart used the same array for the first version of his Symphony No. 40, in 1788.) Schubert’s crisp musical material matches the economical scoring, with a first theme built out of a two-measure cell, and a second theme that incorporates the same distinctive rhythm from the earlier motive.

The slow movement becomes more expansive in its melodies, and a contrasting section that moves to a surprising key has Schubert’s clear stamp, with singing themes set over pulsing accompaniments, as found in many of his songs. The Menuetto is quick and boisterous enough to qualify as a scherzo, Beethoven’s rowdy answer to Haydn’s more polite minuets, while the key of G minor recalls Mozart’s stormy Symphony No. 40. The finale closes the symphony on a lively note, honoring Schubert’s debt to the masters of the previous generation.

Aaron Grad ©2016

Get driving directions and find nearby parking.

Find dining options close to the venue.

View seating charts to find out where you'll be seating.

SPCO concerts are made possible by audience contributions.

For exclusive discounts, behind-the-scenes info, and more:

Sign up for our email club!