Details

Franz Joseph Haydn

Symphony No. 102

After the successes of the 1791 and 1792 concert seasons presented with Johann Peter Salomon, Haydn would have been happy to stay in London. Instead, Prince Anton Esterházy recalled Haydn to Austria, where he spent the next eighteen months. During that time, Haydn gave some lessons to a young firebrand recently arrived in Vienna, one Ludwig van Beethoven.

Haydn arranged a second London visit as soon as he could, and he began composing more symphonies in advance of the trip, which began in February 1794. He stayed through the 1795 spring season, but by then Salomon had disbanded his concert series, so Haydn shifted his presentations to the “Opera Concerts” mounted by the violinist Giovanni Battista Viotti, whose even larger orchestra numbered around sixty players.

Most of the second batch of “London” symphonies added clarinets to the orchestration, and several featured notable effects that inspired nicknames for the works, as in the percussion arsenal of the “Military” Symphony (No. 100), the tick-tock accompaniment of “The Clock” (No. 101) and the iconic timpani lead-in that begins the “Drum Roll” (No. 103). The Symphony No. 102 does not have a descriptive nickname, although it deserves to be known as “The Miracle,” the title ascribed instead to the Symphony No. 96. It was at the premiere of the Symphony No. 102 on February 2, 1795 (and not that of the earlier symphony) that a chandelier crashed to the floor; miraculously, no one was hurt.

The Symphony No. 102 begins with a simple yet striking effect: The home pitch of B-flat, spread among the whole orchestra in several octaves, swells from a piano dynamic and then recedes. (In a nod to his old teacher, Beethoven began his Fourth Symphony with a markedly similar gesture.) The lively body of the movement maintains a thematic link to that initial motive, using held tutti octaves to make surprising pivots to new sections.

The Adagio is an example of Haydn’s self-borrowing; this music appears, in a different key, as the slow movement of a Piano Trio in F-sharp Minor, composed around the same time. The long-lined melodies, beginning in the violins, have a vocal quality about them, and the movement takes on an operatic character as it passes through dramatic minor-key episodes. The Menuet jokes around with three-note tapping figures displaced to cut against the grain of the three-beat meter, while the contrasting trio section is smooth and lyrical, entrusting melodic duties to the mellifluous pairing of oboe and bassoon.

Musicologists have identified the theme of the finale as a Croatian folk tune, specifically, according to Sir William H. Hadow, “the march which is commonly played in Turopol at rustic weddings.” Haydn was born in an area of Austria with large immigrant populations from Croatia and Hungary, and he may have been partly Croatian himself. Later, the long stretches he spent at the remote Eszterháza estate near the Austrian-Hungarian border would have provided more exposure to Slavic traditions.

Aaron Grad ©2012

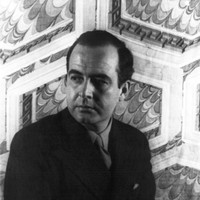

Samuel Barber

Concerto for Violin and Orchestra

Samuel Barber graduated from the Curtis Institute in the same class as Iso Briselli, a Russian-born violinist. Briselli’s patron and guardian, the soap tycoon Samuel Fels, later commissioned Barber to write the violinist a concerto, providing a $500 advance that allowed Barber to work on the score in Europe, until the advent of World War II drove him back to the United States. After Barber delivered the first two movements, the concerto ran into its first trouble when Briselli’s violin teacher, Albert Meiff, wrote to Fels, “The composition possesses beautiful romantic moods, many somber and quite interesting parts typical of that composer—in any event, very interesting. However, it bears a serious defect: it is not a composition gratifying for a violinist to perform. The technical requirements are very far from the requirements of a modern violinist, and … some of the parts are childish in details.”

In light of the feedback he received, Barber made a point of incorporating “brilliant technique” in the perpetual motion finale, which he delivered two months before the planned premiere. A false story that has been widely circulated since its publication in a 1954 biography claims that Briselli then rejected the concerto on the grounds that the finale was unplayable, which Barber countered by setting up a test reading by another violinist. Briselli did object to the finale, but judging from a letter from Barber to Fels, the dispute appeared to be a matter of taste and not technique; the reasons Barber mentioned include complaints that the finale was “not violinistic” and “rather inconsequential.” Barber stood by the “concertino” as he called it in the letter—a title that matched his conception of a work more compact than a grand violin concerto in the nineteenth-century mold—and Fels and Briselli ultimately relinquished their claim on the exclusive performance rights.

The Violin Concerto’s opening movement is indeed lyrical and understated, more an expression of intimate chamber music than virtuosic bluster. The soloist enters with no fanfare at all, launching the soaring first theme right on the downbeat. The other distinctive theme, with its vigorous rhythmic snap, appears only in the orchestra until the soloist finally takes it up in a throbbing coda.

In the central Andante movement, the melodious oboe solo that prefaces the violinist’s entrance is perhaps the greatest concerto melody not written for a soloist since Brahms penned a similar oboe solo in the slow movement of his own Violin Concerto. The solo violin waits patiently through the first quarter of the movement, building anticipation for its delicate entrance and moody counter-theme.

The perpetual motion finale, the source of so much trouble for Barber at the birth of the concerto, is a dazzling tour de force, not just for its rapid figurations—violinists have handled worse—but for its seamless construction and ceaseless variety in the musical material. An accelerated coda has the white-knuckled intensity of a gymnast’s final dismount.

Aaron Grad ©2014

Franz Schubert

Symphony No. 8 in B Minor, Unfinished

Unlike other famous pieces of unfinished music, such as Bach’s Art of Fugue or Mozart’s Requiem, Schubert’s Unfinished Symphony was not cut short by the composer’s death. Schubert lived another six years after completing two movements and sketching a third of his B-minor Symphony, and it is tempting to speculate why he would have abandoned the project. It was certainly his most ambitious symphony to date, eclipsed only by the Great Symphony in C Major he finished three years later. The Unfinished Symphony strayed from symphonic norms, with an unusual choice of key and all of its movements (including the unfinished Scherzo) in triple meter. Historians also believe that Schubert contracted syphilis around January 1823, mere weeks after finishing the first movements of the B-minor Symphony, so it is possible that the physical and emotional toll of the initial stage of the illness impacted his plans for the symphony.

As in much of Schubert’s instrumental music, the B-minor Symphony’s melodic invention demonstrates his highly developed skills as a songwriter, such as in the primary theme played by woodwinds over string accompaniment; it is easy to imagine a setting of the same material for soprano and piano. Departing from the great symphonic strategists Haydn and Beethoven, who would thoroughly explore a few themes and navigate long and ingenious paths between sections, Schubert keeps the focus locked on an exquisite succession of melodies. Instead of milking the transition from the first key area to the second, a single held note and two chords make a graceful pivot to that section’s lovely new theme, this time issued first by the cellos in their baritone range. That melody departs with no transition at all, just a trailing off followed by a jolting C-minor chord.

The second movement, an Andante con moto in E major, takes the central importance of melody even further. Two theme groups alternate, with subtle elaboration and variation, linked by minimal connective tissue. There is an eternal quality to the music, inviting the listener to relish familiar points as they return. The subdued ending after just two movements is not the expected cap to a symphony, but this piece demonstrates from its first measure a reluctance to conform to the Beethoven model of the symphony as a vehicle for transformation and catharsis. Tacking on additional movements would have pushed Schubert’s Unfinished Symphony toward the mold of music that makes a show of going somewhere; as it is, it basks comfortably in deeply felt moods and heartfelt melodies.

Aaron Grad ©2010

About This Program

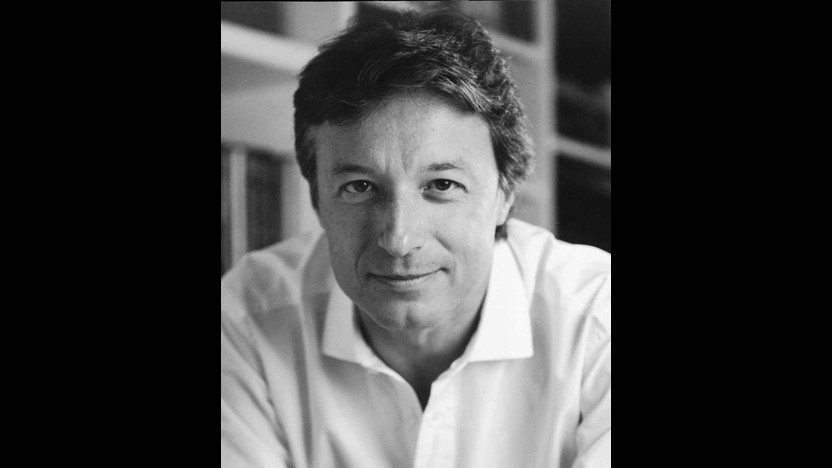

The final program of the 2013-14 season features a selection of orchestral favorites under the skillful hands of Artistic Partner Roberto Abbado. Opening the program is Haydn’s Symphony No. 102, a crowning achievement not only of the composer’s own work, but of the entire Classical repertoire. SPCO Associate Concertmaster Ruggero Allifranchini continues the program with Barber’s passionate Violin Concerto, a beloved gem of the twentieth century, and Schubert’s Unfinished Symphony offers a poetic close to the season.