Alina Ibragimova Plays Beethoven’s Violin Concerto

Jean Sibelius was Finland’s first and greatest musical hero. He rose to fame at the start of the twentieth century on the strengths of his first two symphonies and the tone poem Finlandia — works that gave voice to a burgeoning national identity just when Finland began agitating for independence from Russia — and he did his part to foment change with patriotic songs and populist protest pieces. In that period he circulated with the leading intellectuals in Helsinki, often drinking, smoking and spending far too much in the process, until his concerned wife and friends suggested a move to the country. The family built a remote estate, dubbed Ainola after Sibelius’ wife, Aino, and Sibelius lived there from 1904 until his death 53 years later.

Sibelius composed the Romance in C Major during that time of transition, and the performance he conducted with the Musical Society of Turku (Finland’s oldest orchestra) helped raised funds to cover the construction costs. Composed in the same period as his legendary Violin Concerto, this short Romance for strings honors that genre’s origin as a simple, tuneful form of slow movement.

Aaron Grad ©2024

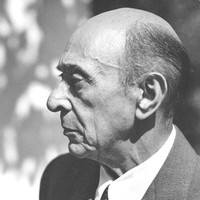

Arnold Schoenberg is most famous — or perhaps infamous — for pioneering atonality and the twelve-tone method of composition. Despite all the “accusations of anarchy and revolution” directed his way over the years, his own view (as he explained in a 1949 lecture) was that his development as a composer “was distinctly evolution, no more exorbitant than that which always has occurred in the history of music.”

The Chamber Symphony No. 2 came from a major inflection point in Schoenberg’s evolution. He started it in 1906 on the heels of the First Chamber Symphony, a hyper-dense score that pushed the logic of tonality to its breaking point. While midstream on the Second Chamber Symphony, he began experimenting with a new way of approaching his craft in other works, developing a style that drifted away from tonal rules toward a free atonality, guided by his own intuition. He tried picking the Chamber Symphony back up in 1911 and 1916, but the gap between his old and new working methods left him at an impasse.

Schoenberg evolved even further in the 1920s with his twelve-tone system, and with the rise of the Nazis in the 1930s, the Jewish composer went into exile, settling in Los Angeles. With some prodding by Fritz Stiedry, another Austrian expatriate who led an orchestra in New York, Schoenberg took up the Second Chamber Symphony once more, 33 years after he began it. He wrote to Stiedry, “I have been working on the second chamber symphony for a month now. I spend most of the time trying to discover ‘What did the author mean here?’ My style has now become very consolidated and it is now effortful to unify what I wrote down back then, justifiably trusting in my feeling for form, with my current extensive requirements for ‘visible logic.’”

Schoenberg only made minor changes in the Adagio first movement, adjusting some of the accompanying textures and adding twenty new measures at the end. The fiery second movement, on the other hand, required about half new material, including a final, epilogue-like section. The total effect is remarkably cohesive for a score assembled at opposite ends of Schoenberg’s continual evolution as a composer.

Aaron Grad ©2024

Listen to Audio

Listen to Audio

For musicians in Ludwig van Beethoven’s Vienna, one of the more effective ways to make a living was to produce concerts for their own benefit. Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart had specialized in those during his peak Viennese years (often debuting his new piano concertos there), and Beethoven followed suit, even after his encroaching deafness began to interfere with his performing career. When Beethoven’s friend Franz Clement asked for a concerto to play on his own benefit concert, the composer felt obliged to come through for the violinist who had introduced Beethoven’s Third Symphony on an earlier benefit concert, and who had been instrumental in getting the opera Fidelio produced.

Beethoven threw together an entire Violin Concerto with uncharacteristic speed, cutting it so close that the soloist supposedly had to sight-read the highly challenging part. Perhaps it was that lack of preparation time that left the public unmoved, sending the concerto into a dormant state. It didn’t catch on until Felix Mendelssohn brought the concerto back to life in an astonishing collaboration with a 12-year-old wunderkind, the violinist Joseph Joachim.

The Violin Concerto starts with a quintessential Beethoven theme: a single note, D, struck five consecutive times by the timpanist. This modest tapping motive proves to be the backbone of the substantial first movement, an outcome typical of Beethoven’s “middle period,” when he mastered the art of distilling musical ingredients down to their purest essence. One exceptionally refined moment comes just after the first movement cadenza, when the violin offers a guileless melody over a naked accompaniment of plucked strings.

The slow movement continues the rarified mood with a stately theme and variations accompanied only by the lower winds and muted strings. The Rondo finale, reached without pause through a solo cadenza, supplies the concerto with a more extroverted conclusion. Taking a page from Franz Joseph Haydn, who loved to introduce a theme softly and then hammer it hard the second time, Beethoven goes a step farther by delaying the impact until after two melodic cycles, the second voiced even more delicately than the first.

Aaron Grad ©2024

Arnold Schoenberg takes concertgoers on a darkly fantastic adventure with his Second Chamber Symphony. He began composing the work as early as 1906 but didn’t complete it until thirty years later. Though Schoenberg is known for developing the “twelve-tone” system, this work harkens back to the composer’s warm Romantic style.

Get driving directions and find nearby parking.

Find dining options close to the venue.

View seating charts to find out where you'll be seating.

Get driving directions and find nearby parking.

Find dining options close to the venue.

View seating charts to find out where you'll be seating.