Details

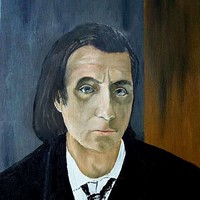

Alfred Schnittke

Moz-Art à la Haydn for Two Violins and Strings

Alfred Schnittke received his earliest musical training in Vienna from 1946 to 1948, while his father served there as a translator. Shortly after his graduation from the Moscow Conservatory in 1958, he made waves with the oratorio Nagasaki, which received sharp criticism from the government-backed Union of Composers. Like Shostakovich, an early target of the Union, Schnittke proved resilient in the face of such resistance, and he managed to sustain a career by scoring state-sponsored films, lecturing, and teaching for a decade at his alma mater. Through a string of major concert works, especially concertos, he developed a “polystylistic” sound that merged elements of serialism, chance, pastiche, Romanticism, church music, bawdy songs, and other components. His music started to spread to the West through champions such as Gidon Kremer, but just as Gorbachev-era reforms loosened Soviet travel restrictions, Schnittke suffered the first of a series of debilitating strokes. He continued to compose, developing a darker, more introspective style, and moved to Hamburg, where he spent his final eight years.

In 1977, Schnittke completed his first concerto grosso, a deep and haunting meditation on Baroque conventions, scored for two violins and small ensemble. The same year, he created another piece with historical references and two violin soloists, the unabashedly comical Moz-Art à la Haydn. As different as the works are in mood, they both grew out of Schnittke’s extraordinary ability to fragment and reassemble diverse components in new and unexpected ways. The raw ingredients for Moz-Art à la Haydn, as the title suggests, come from the two legends of the Classical era. (The split “Moz-Art” also accomplishes some word play in German, roughly meaning “Sort of.”) There are snippets from a humorous pantomime Mozart wrote in 1783 (K. 446), of which only the first violin part and some sketches survived, as well as other winking references, including a taste of Mozart’s Symphony No. 40. The spirit of Haydn comes across in the witty sarcasm, and also in a structural parallel to the “Farewell” Symphony No. 45. According to legend, Haydn intended to make a subtle protest to Prince Nikolaus Esterházy, who had kept his court musicians at the summer palace (and away from their families in the city) longer than expected. Haydn made his point in an unusual slow coda appended to the finale, in which he instructed the musicians, as their parts dropped out in turn, to blow out the candles on their music stands and leave the stage until just two muted violins remained. (Apparently, Prince Nikolaus got the joke; he released the musicians the next day.) Moz-Art à la Haydn expands the manipulation of lights and staging, not just dissolving into an empty stage and darkness, but also coordinating a sudden burst from total darkness into light and specifying midstream stage maneuvers for the split string ensemble.

Like any great parody, Moz-Art à la Haydn entertains while also challenging the status quo on details as elemental as light, stage arrangement and tuning, and ideas as broad as the Classical style. It is as if Schnittke turned a dial that filtered pure, recognizable forms and colors into kaleidoscopic hallucinations, forcing the performers and audiences to mentally piece together that which is true and meaningful — or at least to have a good chuckle in the process.

Aaron Grad ©2011

Listen to Audio

Listen to Audio

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart

Violin Concerto No. 3

Mozart’s childhood feats at the keyboard overshadowed another of his great talents: playing the violin. His father was an influential teacher and the author of a seminal book on violin technique, so it figured that Mozart would pick up stringed instruments. (He also had a special affection for the viola, playing it in chamber music situations throughout his life.) Mozart wrote five violin concertos, all during his teenage years, when his official position had him working alongside his father in the service of Salzburg’s archbishop. With no record of any other performer or commission involved, we can surmise that Mozart wrote the violin concertos with the intention of performing the solo parts himself. Such works, along with the many symphonies, serenades and divertimentos from that time, were perfect fare for the side gigs he booked entertaining Salzburg’s wealthy families.

The violin writing in the Third Violin Concerto’s opening Allegro movement is full of three-note chords, in both the solo part and the orchestra. The chords give the main theme extra panache and power, and their idiomatic voicings show that Mozart knew how to achieve maximum effect on his secondary instrument.

Out of all five of Mozart’s violin concertos, this work’s central Adagio is the only movement in which two flutes replace the oboes. (Presumably the oboists in Salzburg doubled on flute.) The solo violin’s long, arcing phrases sound like they could come from the mouth of an operatic soprano; there is even a bit of a “diva” moment when the violin intrudes on the orchestra’s final coda to offer one last statement of the main theme.

In the Rondeau finale, one of the contrasting sections borrows a folk tune from the vicinity of Strasbourg, near the border between France and Germany, leading Mozart and others to dub this the “Strassburger” Concerto. Droning double-stops and folksy fiddling contribute to the local color.

Aaron Grad ©2017

Jean Françaix

Quartet for Winds

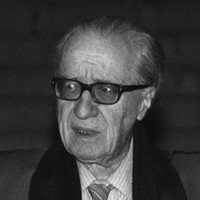

Joseph Haydn

Symphony No. 45, Farewell

When Prince Nikolaus Esterházy completed a lavish country palace in 1766, the workload for his tireless Kapellmeister, Joseph Haydn, increased dramatically. The “summer” seasons at the estate stretched to be nearly year-round, and all the while Haydn had to produce operas, provide music for church services, mount concerts and attend to any other musical needs for his insatiable patron. “In Eszterháza,” Haydn acknowledged, “I was forced to become original.”

Some of Haydn’s most original efforts in the late 1760s and 1770s reflected an artistic trend that has been dubbed Sturm und Drang (“Storm and Stress”) after a play of the same name. From literature to painting to playwriting, artists dared to explore emotional extremes and dark discomfort; for Haydn, it led to his first symphonies constructed in minor keys, including the Symphony No. 45, dubbed Farewell.

The legend behind the nickname is that Haydn intended to make a subtle protest to the prince, who had kept his court musicians at the summer palace (and away from their families in the city) longer than expected. Haydn made his point in an unusual slow coda appended to the finale, in which he instructed the musicians, as their parts dropped out in turn, to blow out the candles on their music stands and leave the stage until just two muted violins remained. Apparently, Prince Nikolaus got the joke, and he released the musicians the next day.

Aaron Grad ©2018

About This Program

With the ability to “collapse any sense of distance between performer and listener” (The Guardian), world-renowned violinist Alina Ibragimova returns to the Ordway to lead the SPCO on a journey through lighthearted, spirited works by Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, Joseph Haydn and those they inspired. Alfred Schnittke’s Moz-Art à la Haydn is an out-of-the-box take on an unfinished musical fragment by Mozart, written in the humorous spirit of the two titular composers known for their humor. With a ghostly “fun house atmosphere” (New York Times) full of musical quotations, the work involves dueling violinists, lighting effects, and an ending reminiscent of Haydn’s Farewell Symphony — hang on tight for this program full of whimsy à la Mozart!

Contribute

SPCO concerts are made possible by audience contributions.

Newsletter

For exclusive discounts, behind-the-scenes info, and more:

Sign up for our email club!