American Romantics

Sponsored By

- September 20, 2012

- September 21, 2012

Sponsored By

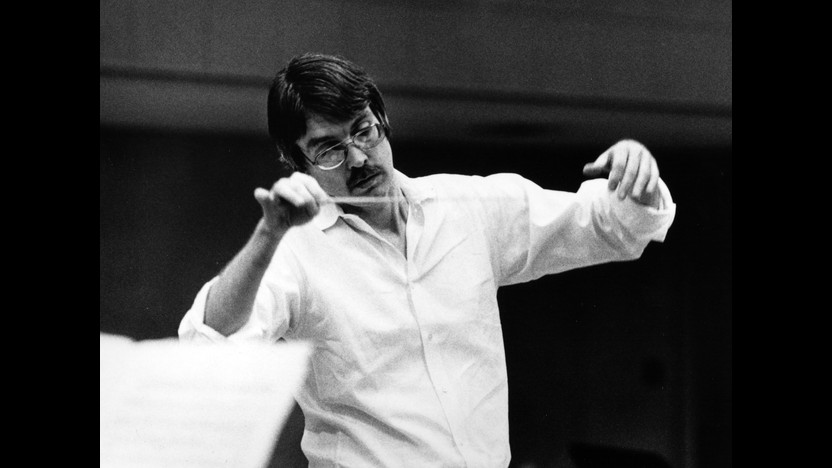

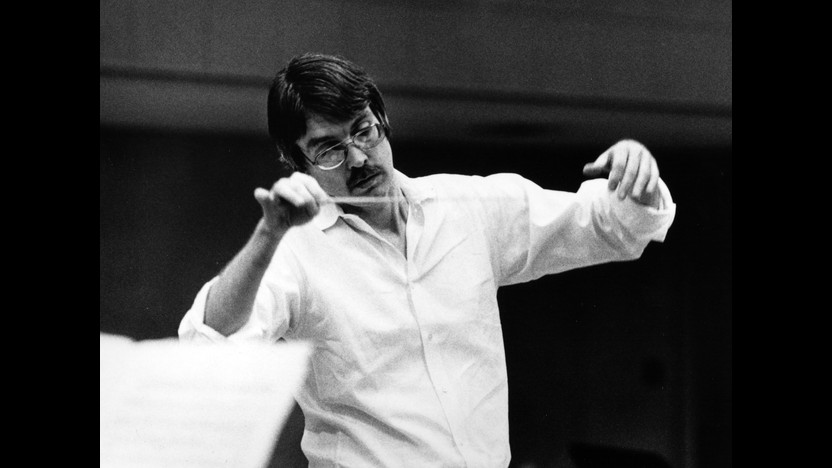

Walter Piston was one of the most respected American composers of the last century. Born in Maine, he was eleven when his family moved to Boston. Piston played saxophone in a Navy band during World War I and then attended Harvard University from 1919 to 1924. Like many of his American contemporaries, Piston completed his education in Paris, where he studied with Nadia Boulanger. He returned to the United States in 1926 and began teaching at Harvard, a post he held until his retirement in 1960. He composed slowly, mostly during summer breaks from teaching, but he managed to produce a steady stream of significant works. He wrote extensively for orchestral forces, including eleven works for the Boston Symphony Orchestra and a total of eight symphonies, two of which were awarded Pulitzer Prizes (the Third and Seventh Symphonies, in 1948 and 1961, respectively). Piston’s other lasting legacy was as the author of treatises on theory, counterpoint, and orchestration; all are authoritative manuals that remain on the shelves of composers to this day.

When the International Society for Contemporary Music commissioned a new work from Piston, it gave him total leeway to choose the instrumentation and form. He settled on a mixed chamber ensemble of four woodwinds and five strings and designed the work as a divertimento in three movements. The title and lean instrumentation call to mind the Classical divertimento, a type of composition that was typically used as lighthearted entertainment at social gatherings.

Composed shortly after the end of World War II, the Divertimento for Nine Instruments displays an effervescence that contrasts with the heavier emotional tenor of Piston’s wartime works. The musical language in the opening Allegro movement is dry and airy, with punctuated accents and bright sonorities reminiscent of Stravinsky’s neoclassicism. The heart of the work is the longer middle movement, a set of variations in a tranquillo tempo that shows off Piston’s delicate touch with counterpoint and blended combinations of instrumental color. Snapping pizzicato and clucking winds give the Vivo finale an air of mischief, offsetting the more formal fugal elements.

Aaron Grad ©2012

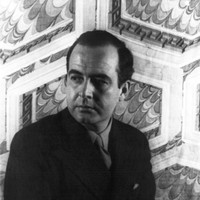

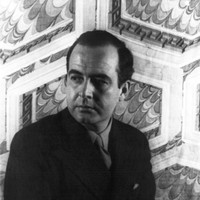

Samuel Barber enrolled in the founding class at Philadelphia’s Curtis Institute of Music at the age of 14. He went on to win the American Academy’s prestigious Rome Prize, which bankrolled his Italian residency from 1935 to 1937. During that time, Barber composed his String Quartet (Opus 11) as well as an adaptation for string orchestra of the quartet’s slow movement, a haunting Adagio that was destined to become one of the most recognizable compositions of the century.

The string orchestra version of the Adagio made its public debut in 1938 during a radio broadcast by Arturo Toscanini and the NBC Symphony Orchestra. The work became an instant favorite with the public, and its success launched Barber’s international career.

The first significant use of the Adagio as music for mourning came in 1945, when radio stations broadcast the work following the announcement of Franklin D. Roosevelt’s death. The tradition continued with performances at the funerals of John F. Kennedy, Grace Kelly and Leonard Bernstein, among many others. The score has also appeared in many films, from its wrenching role in Platoon to a sardonic cameo in Amélie.

The musical language of Barber’s Adagio is deceptively simple. Melodically, lines move in long strands of rising steps, evoking a sense of reaching and yearning. Harmonically, the energy builds through drawn-out suspensions, creating momentary surges of tension and release over a glacially slow sequence of bass notes. It is a simple and elegant design, one that evokes as much emotion, note-for-note, as any piece of music in recorded history.

Aaron Grad ©2022

<strong>Composer’s Note</strong>

Early in 1987 when flutist Marya Martin, cofounder of the Bridgehampton Chamber Music Festival, approached me about a piece for herself and her four colleagues—violinists Ida and Ani Kavafian, cellist Fred Sherry, and pianist André-Michel Schub—specifying that it last from twenty to twenty-five minutes, I was intrigued by the unprecedented mixture of instruments. When Marya added that an auspicious premiere would take place in Bridgehampton during July of 1988, with three more performances the following March at the Chamber Music Society of Lincoln Center in New York, the intrigue turned to ambition. I composed the twenty-minute, five-movement work in New York and Nantucket between July and December 1987 and called it Bright Music.

What more can I say? The history, the secret of how any such work comes to be is unfathomable, except by outside authorities who invariably provide canny but irrelevant exegeses. That creative process is like a placenta which has both shielded and coaxed the growth of the work; but once the work is delivered, the afterbirth is devoured and forgotten by the no-longer-pregnant parent.

Composers nevertheless usually like to chat about their music. One will adopt an aesthetic stance and tell you about inspiration, emotional convictions, even sunsets. Another might gossip: was he in love or otherwise ailing during the feat, and if so, did this affect the content? (People always want to know how such happy sounds can be penned by one so sad.) I, meanwhile, having reexamined the score as an objective critic might, will briefly give you a few tangible pointers.

I am struck by how the composer of Bright Music—who insofar as he is known at all is known for vocal pieces which are spacious and nonrepetitive—has here constructed not from themes but from motives, fragments. Fandango, for example, which is actually a rondo, is built from a ritornello of four adjacent notes, E-D-G-F. The net effect is meant to evoke a rat in an ashcan, commencing with spasmodic flurries and starts and stops and then gusting into a raucous mazurka. Pierrot is a meditation on Picasso’s early Blue-Period paintings, although this was decided ex post facto. Dance – Song – Dance is a scherzo based on a major triad, followed by a long lament based on the same triad in slow motion that returns to the scherzo and whirls to a close. Another Dream is a series of solos by flute and strings that weave themselves slowly around the piano’s forty-eight-measure ostinato in 9/8. Finally, Chopin is the wisp of an echo of that composer’s B-flat Minor Piano Sonata.

After the piece was done, the only problem remaining was what to call it. Originally named Chamber Music (had the term ever been used specifically rather than generically as a title?), that seemed just too dull. Sylvia Goldstein came up with the present title—apt, since as I grow older my music grows more optimistic.

Ned Rorem ©

In 1953, the celebrated composer Samuel Barber accepted a commission from the Chamber Music Society of Detroit. He even agreed to forgo an up-front payment, instead endorsing a scheme by which the audience would donate at the premiere. The work was meant to be a septet for winds, strings, and piano, to be premiered by the principal players of the Detroit Symphony Orchestra in 1954 in celebration of the society’s tenth anniversary; Barber did not manage to deliver the work until 1955, and it emerged not as a mixed septet but as a woodwind quintet. Despite those hiccups, Barber’s Summer Music was well received, and his sole work for winds has entered the standard repertoire of quintets around the world.

While preparing to compose Summer Music, Barber consulted with the esteemed New York Woodwind Quintet, and he tailored the work to the personalities and abilities of the five members. Soon after the premiere, Barber issued a revised version of Summer Music, which the New York Woodwind Quintet took on a three-month tour of the Americas.

Summer Music drew source material from an unpublished orchestral score from 1945 entitled Horizon. Barber recycled several themes into the quintet, including the opening melody introduced by the horn and bassoon at a “slow and indolent” tempo. The single-movement work returns periodically to this relaxed material, interspersed with more buoyant and agitated episodes. There is no programmatic thread, per se; as Barber quipped, “It’s supposed to be evocative of summer—summer meaning languid, not killing mosquitoes.”

Aaron Grad ©2012

<strong>Composer’s Note</strong>

The title page of the Piano Quintet (1981) bears the following dedication: “To Georgia O’Keeffe with affection and gratitude, from the artists, directors, and friends of the Santa Fe Chamber Festival.” The piece was begun at Token Creek, Wisconsin, four miles from Sun Prairie, where its dedicatee, Georgia O’Keeffe, grew up. It was completed during the spring when I was Resident Composer at the American Academy in Rome.

Certain aims have governed my recent work, never more than in this piece: to give the medium what it requires, to strike a balance between the hermetic and the easily reachable, and to make clear form of inherently complex emotion. In looking at the work of Georgia O’Keeffe, it struck me that the point of contact was this characteristically American search for clarity out of complex forces. In opening my piece, I thought of the unfilled parts of her canvases, the open space, and the pleasure of leaving something out.

This opening strain dominates the first movement of the quintet in spite of the energy of the contrasting material. The amplitude of the discourse is contradicted by the three concise character pieces which follow. The final elegy is, I trust, the only direct reference to the difficult circumstances under which the piece was composed, reflecting in its open-ended form the unresolved questions it poses at every turn.

John Harbison ©

TRAFFIC ALERT FOR THURSDAY: Please be aware that we anticipate travel delays prior to our concert on THURSDAY, SEPTEMBER 20 at TRINITY LUTHERAN CHURCH due to road construction on Third Street in Stillwater. You may want to allow extra time for travel and parking.

TRAFFIC ALERT FOR SUNDAY: Please be aware that we anticipate travel delays prior to our concert on SUNDAY, SEPTEMBER 23 at BENSON GREAT HALL due to road construction on I-694, Hwy 10 and Snelling Ave. You may want to allow extra time for travel and parking. Click here for more information.

Get driving directions and find nearby parking.

Find dining options close to the venue.

View seating charts to find out where you'll be seating.

Get driving directions and find nearby parking.

Find dining options close to the venue.

View seating charts to find out where you'll be seating.