Baroque Concertos and Haydn’s Fire Symphony

Francesco Geminiani, the son of a professional violinist, trained for a time with Arcangelo Corelli (1653-1713), the most influential composer and teacher during Italy’s violin heyday. Geminiani made the wise decision in 1714 to relocate to London, a city obsessed with Corelli and happy to welcome one of the master’s disciples. Besides performing and publishing his own sonatas and concertos, Geminiani found a winning formula when he converted Corelli’s beloved Opus 5 (a set of twelve violin sonatas) into concerti grossi.

The final sonata from Opus 5 contained Corelli’s variations on La Follia, a standard chord pattern that had fascinated musicians for centuries, dating back at least as far as 15th-century Portugal. Geminiani later recalled hearing Corelli “acknowledge the Satisfaction he took in composing it, and the Value he set upon it.” Geminiani’s arrangement preserved the character of each colorful variation while elaborating and reassigning the material for multiple soloists within a larger ensemble. Expanding on Corelli’s usual combination of two violins and cello as soloists, this concerto grosso adds a viola to the solo group, balanced against the string orchestra and basso continuo.

Aaron Grad ©2017

Domenico Cimarosa was the king of Italian comic opera in the closing years of the eighteenth century—which made him one of the most respected and envied composers in the world. From 1787–1791, he was maestro di cappella to Catherine the Great in Saint Petersburg, followed by two years in Vienna serving the same role to Leopold II, the Holy Roman Emperor. While Viennese composers learned plenty from his operas, Cimarosa allowed the influence to flow the other direction as well, paying close attention to the instrumental innovations crystallized by Haydn and Mozart. That influence certainly colors the Concerto in G Major for Two Flutes that Cimarosa composed in 1793, shortly after returning to his native Naples. He actually wrote it for a private performance hosted by the ambassador from Vienna, a member of the well-heeled Esterházy family (Haydn’s employer) and a patron likely to appreciate this musical nod to the Viennese masters.

The fast outer movements demonstrate Cimarosa’s fluency in the Sinfonia concertante genre, an update on the older Italian style of concerto for multiple soloists. The idiomatic flute solos take advantage of the instrument’s wide pitch compass, and the writing for the large accompanying ensemble—including clarinets, horns and bassoons—gives the tutti passages a symphonic depth of sound. If the main theme of the slow movement sounds familiar, you are probably thinking of a strikingly similar tune incorporated 20 years later into The Barber of Seville by Rossini, a composer profoundly indebted to Cimarosa.

Aaron Grad ©2017

Antonio Vivaldi took after his father in playing the violin, but The Red Priest, as the ginger-haired composer came to be called, trained for a life in the church instead of studying music. Ordained in 1703, Vivaldi took a job at the Ospedale della Pietà, a school for orphaned girls in Venice. As their violin teacher, Vivaldi used the talented instrumentalists under his care to try out and refine his numerous concertos. Even before his first breakthrough collection of concertos reached the public in 1711, private manuscripts traded among musicians sent Vivaldi’s influence rippling through Europe. The success of his published scores cemented his international fame, bringing him into contact with the likes of Charles VI, the Holy Roman Emperor. Vivaldi presented Charles with manuscripts to 12 concertos when they met in 1728. It’s not known exactly how one of those concertos ended up with the nickname Il favorito—it might have been the Emperor’s favorite, or maybe Vivaldi himself singled it out.

Vivaldi developed or codified some of the most important aspects of concerto style, such as the fast-slow-fast sequence of movements and the use of ritornello structure as a way to differentiate sections for the soloist and full ensemble. This ritornello form is particularly effective when the recurring theme is bold and recognizable, like the rising arpeggio that locks in the key center of E minor at the beginning of Il favorito. (No composer absorbed this lesson better than Bach, an ardent fan and imitator of Vivaldi’s concertos.) The central Andante movement thins the accompaniment to pulsing chords from the violins and violas, exposing every delicate nuance of the florid solo part.

The rhythmic leaps of the finale borrow from the hunt-inspired finale of Autumn from The Four Seasons, printed in 1725. Considering that Vivaldi sold 140 concertos to the Pietà just in the years 1723–1729, his penchant for self-borrowing is understandable.

Aaron Grad ©2017

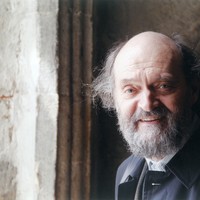

Before the Estonian composer Arvo Pärt developed his hallmark sound—a style he calls tintinnabuli, from the Latin for “little bells”—he wrote strident neo-classical and serial works that bucked Soviet orthodoxy. He reached an artistic crisis in 1968, and over the next eight years he barely composed. His new style only emerged after detailed investigations of Gregorian chant and other early music, leading to a series of breakthrough scores from 1976-77, including Cantus in Memory of Benjamin Britten, Tabula Rasa, and Fratres. This last work, played initially by an Estonian early music ensemble, is built on an elegant framework of variations that allows it to be transported to any combination of instruments. A legendary album released by ECM Records in 1984 included two versions: one for violin and piano (played by Gidon Kremer and Keith Jarrett) and another for 12 cellos (featuring members of the Berlin Philharmonic). This record resonated with an exceptionally broad and diverse audience, cementing Pärt’s reputation on both sides of the Atlantic.

The version of Fratres for string quartet, first performed in 1986, emphasizes the austerity and blend of the musical lines, recalling the centuries-old tradition of the viol consort. The title, Latin for “brothers,” underscores this music’s connection to even older forms of monastic singing. SPCO violinist Daria Adams has adapted this version, with multiple strings on each part, especially for the architecture and acoustics of the Ordway Concert Hall.

Aaron Grad ©2017

Franz Joseph Haydn trained at a prestigious choir school in Vienna until his voice broke at 17. He spent the next twelve years teaching kids and later working for a count of modest means, until at 29 he landed the job that set him on the course to become the most famous composer in the world: In 1761, he joined the fabulously wealthy Esterházy family as their Vice-Kapellmeister, followed by a promotion five years later to Kapellmeister. Initially he was responsible for producing two concerts each week with the court’s private orchestra, and in later years his duties grew to include writing and producing operas. He spent months on end cloistered at the family’s remote summer palace, providing entertainment for the insatiable Prince Nikolaus Esterházy, a pressure-cooker environment in which, as Haydn later wrote, “I was forced to become original.”

One new direction Haydn explored in the late 1760s and early 1770s was the “Sturm und Drang” (“Storm and Stress”) aesthetic that was also cropping up in the theater, literature and art of the time. This tendency toward heightened emotion and drama tends to be associated with Haydn’s music in minor keys, but the same extremes of expression fueled major-key symphonies as well, including the symphony known by the nickname “Fire,” composed around 1768.

The Symphony No. 59 is fiery indeed, especially in the unusually speedy Presto first movement punctuated by shuddering bow strokes from the violins and forte blasts from the horns. The slow movement’s key setting of A-minor brings an unexpected chill to the atmosphere, and the Menuet reinforces the dichotomy of major and minor keys. The finale, heralded by horns and oboes, bristles with the manic energy of a hunt.

Aaron Grad ©2025

Get driving directions and find nearby parking.

Find dining options close to the venue.

View seating charts to find out where you'll be seating.

SPCO concerts are made possible by audience contributions.

For exclusive discounts, behind-the-scenes info, and more:

Sign up for our email club!