Beethoven’s Eroica Symphony

Before Richard Strauss fell under the spell of Richard Wagner’s music at age seventeen, his most impactful mentor was his own father. Franz Strauss, the principal horn player in the Munich court orchestra, earned a reputation as one of the finest performers ever on his instrument. He was also a composer and a conductor, leading an amateur orchestra that gave his son a proving ground for his earliest attempts at orchestration.

The Serenade for winds that Richard Strauss composed in 1881 aligned with the Classical style championed by his father. The title reflected the eighteenth-century tradition of light music for an evening gathering, and the instrumentation resembled Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart’s Serenade No. 10 (“Gran Partita”) for thirteen players. The Serenade was the first piece by Strauss to be performed outside of Munich, and it remains among the earliest of his works in the active repertoire.

The Serenade enters at a relaxed Andante tempo, introducing its first theme in a chorale of balanced, gentle chords. Throughout the single movement, the scoring is impeccably clear and balanced, proving that the teenaged Strauss made the most of the knowledge and access offered by his father. Franz Strauss must have been especially proud of the warm and regal music his son wrote for the ensemble’s four horns.

Aaron Grad ©2023

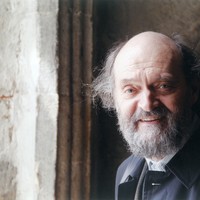

The incandescent musical language of Estonian composer Arvo Pärt has won him a global cult following, and from many corners. Violinist Gidon Kremer, one of Pärt’s most prominent champions, has praised his work as “a cleansing of all the noise that surrounds us.” Rock star Michael Stipe of R.E.M. fame has called Pärt’s music “a house on fire and an infinite calm.”

Pärt himself offers a more precise term to characterize his work: tintinnabuli, the tonal technique he developed in the late 1970s that has become the DNA of his language. The term—literally, “bells”—is named for the bell-like quality of a triadic chord (eg, C major: C–E–G). Technically: tintinnabuli constitutes a two-part texture, juxtaposing a melodic voice, moving primarily by step around a central pitch, and a tintinnabuli voice, which surrounds the melody with the notes of the tonic triad.

Per Pärt: “Tintinnabulation is an area I sometimes wander into when I am searching for answers – in my life, my music, my work. In my dark hours, I have the certain feeling that everything outside this one thing has no meaning. The complex and many-faceted only confuses me, and I must search for unity. What is it, this one thing, and how do I find my way to it? Traces of this perfect thing appear in many guises – and everything that is unimportant falls away. Tintinnabulation is like this.”

Though not his first work to use this technique, Fratres is perhaps the most emblematic (and is Pärt’s signature instrumental work besides; it has been featured prominently in numerous films, including Paul Thomas Anderson’s There Will Be Blood). Pärt originally composed the work in 1977 for twelve instruments, and thereafter adapted it for other ensembles. Unique to the present arrangement, the aural spatiality between solo violin and string orchestra creates a vast chasm; sustained string textures follow the soloist’s frenetic opening figurations, seemingly launching the listener into zero gravity. The sonic separation between bass drum and claves further expands the space.

The austerity of Pärt’s materials is not beyond analysis, but it ultimately points to a peculiarly mystical quality. This quality, in evidence throughout Fratres, is the essence of Pärt’s musical identity. The most precise assessment comes again from Pärt in extramusical terms: “I could compare my music to white light which contains all colours. Only a prism can divide the colours and make them appear; this prism could be the spirit of the listener.”

Patrick Castillo ©2015

After writing a monumental symphony that dwarfed his two previous efforts (and those of all composers who came before him), Ludwig van Beethoven gave the Symphony No. 3 in E-flat Major the subtitle of "Bonaparte," honoring the military mastermind of Revolutionary France. But the composer’s adulation turned to disgust in 1804, when he learned that Napoleon had crowned himself Emperor; according to the student who delivered the disturbing news, Ferdinand Ries, “Beethoven went to the table, seized the top of the title-page, tore it in half and threw it on the floor.” When preparing the symphony for publication in 1806, Beethoven re-titled it "Sinfonia eroica, composed to celebrate the memory of a great man,” without specifying who that other hero was.

The defining motive of the Eroica Symphony’s first movement is a rocking cello strain that trails into foreign harmonies after four measures. As the central development section closes, a French horn makes a surprise entrance with a recapitulation of that same theme a few measures ahead of schedule — an effect so unexpected that even Beethoven’s student Ries, upon hearing the symphony for the first time, suspected the horn player of having lost count of the measures.

The symphony’s second movement, labeled a funeral march, sinks into a prolonged state of despair that might induce misery if not for its undeniable grace and beauty. A major-key interlude, providing respite, incorporates an arpeggiated accompaniment that recalls the gentle sway of the first movement. After returning to the minor key, the appearance of fugal counterpoint reinforces the profound, ceremonial atmosphere of the funeral march.

Out of this grief comes a giddy Scherzo, a symphonic construct that Beethoven popularized as an alternative to Franz Joseph Haydn’s slower, tamer minuets. A contrasting trio section features the three horns in vigorous hunting calls.

The finale, built as a theme and variations, incorporates material from the ballet The Creatures of Prometheus that Beethoven had also used in an earlier set of piano variations. A short but fiery introduction gives way to an unusual presentation of the theme, reduced to its bare skeleton.

Aaron Grad ©2024

Get driving directions and find nearby parking.

Find dining options close to the venue.

View seating charts to find out where you'll be seating.

SPCO concerts are made possible by audience contributions.

For exclusive discounts, behind-the-scenes info, and more:

Sign up for our email club!