Season Finale: Beethoven’s First Symphony

Rewind my life a bit and you might find a particular week in 2003 when I was researching the art of Italian Futurist Giacomo Balla for a term paper, watching my roommates play a car racing video game called Gran Turismo and thinking about the legacy of baroque string virtuosity as a point of departure for my next project. It didn’t take long before I felt the resonances between these different activities, and it was out of their unexpected convergence that this piece was born.

Gran Turismo is dedicated to the students of Robert Lipsett, who premiered the work at USC and have since performed it extensively. It is the recipient of the 2005 Leo Kaplan Prize from ASCAP.

— © Andrew Norman

Andrew Norman ©2005

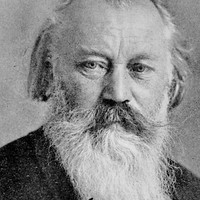

Johannes Brahms wanted desperately to live up to the promise his late mentor Robert Schumann had seen in him as a budding master of the orchestra, but first, the young composer had to find a way to make his reverence for the music of the past an asset, rather than an obstacle. The shadow that darkened his path most frighteningly was that of Ludwig van Beethoven, and it was not until he was in his forties that Brahms found his footing with two of Beethoven’s signature genres, symphonies and string quartets.

At a time when the path to immortality was far from certain for Brahms, a series of experiments with larger forms provided a crucial way forward. Between 1857 and 1859 he drafted two Serenades rooted in the type of casual evening entertainment adored in Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart’s Austria, which allowed for a detour around the serious implications of the symphony. The First Serenade began in a compact form as a nonet for winds and strings, and the Second Serenade emerged a year later with a limited scoring of its own that omitted violins from the standard string complement. That instrumentation shaped the piece’s personality, emphasizing the woodwind choir (and its outdoor associations stretching back to Mozart’s time), as heard in the simple chorale that begins the work.

Brahms’ reckoning with the past also fuels the three central movements. A tidy Scherzo opens into an unexpectedly broad and luminous trio section; the somber, Baroque-tinged opening of the Adagio non troppo provides the raw material for a lush and haunting core; the Quasi menuetto balances naïve dance music (perhaps the measured steps of someone learning to dance) with a contrasting section that builds a halting melody. The Rondo finale has something of a hunting character in the style of Haydn, adding a piccolo to contribute extra brightness and shimmer.

Aaron Grad ©2023

Listen to Audio

Listen to Audio

Ludwig van Beethoven, born into a musical family in the German city of Bonn, left his hometown for Vienna in November of 1792, at the age of 21. The aim of the trip, as his patron Count Ferdinand von Waldstein famously put it, was for the young composer to “receive Mozart’s spirit from Haydn’s hands.” The Elector of Bonn had released Beethoven from his performing and composing duties, with the expectation that he would study for a time with Haydn and then return to serve the court that had employed three generations of the Beethoven family.

Beethoven did study with Haydn, working mainly on counterpoint, but their short-lived tutelage ended when Haydn accepted an offer to spend a season in London, at which point he passed Beethoven off to another teacher. Beethoven’s period of study with Haydn had only a modest impact on his composing, but his chance to test the waters in the Vienna proved life-altering. Filling a void left by Mozart’s death in 1791, Beethoven was able to establish himself as the city’s premier keyboard virtuoso and improviser. He cut his ties with Bonn and pieced together enough work to embark on a freelance career.

Early on, Beethoven shied away from Haydn’s two signature genres: the symphony and the string quartet. Beethoven finally wrote his first quartets, a set of six grouped as Opus 18, between 1798 and 1800. As for symphonies, Beethoven made an attempt in 1795-96 (after hearing Haydn’s London Symphonies), but he did not complete one until 1800. He debuted the work on April 2 on his first benefit concert at the Burgtheater, the same venue where Mozart had presented his own popular concert series.

Beethoven’s First Symphony honors the Viennese tradition of Haydn and Mozart, and yet it also contains a germ of independence. The most striking departure comes in the very first sonority, an unstable chord that resolves away from the home key and only cycles back to the proper tonal center of C major after a drawn-out, tantalizing introduction. When the main theme enters in the new Allegro con brio tempo, it plays with a figure that repeatedly confirms the proper home key, as if to brush away the initial uncertainty.

In a sign of the interconnectivity that distinguishes all of Beethoven’s symphonies, the second movement starts with the same ascending interval (a perfect fourth) that was so central in the first movement. A distinguishing characteristic of this slow movement is its rich and independent writing for winds, with a scoring that includes trumpets and timpani.

The third movement, though labeled a minuet, is closer in spirit to the wild scherzos of the later symphonies. The contrasting trio section showcases Beethoven’s keen sense of humor, with scampering runs in the strings popping up between chorale phrases in the woodwinds. The finale brings this fledgling symphony full circle with another slow introduction. The violins test an ascending scale, adding a note at a time; when they reach the top of the octave, they launch a bright and hearty valediction.

— © Aaron Grad

Aaron Grad ©2017

Get driving directions and find nearby parking.

Find dining options close to the venue.

View seating charts to find out where you'll be seating.

SPCO concerts are made possible by audience contributions.

For exclusive discounts, behind-the-scenes info, and more:

Sign up for our email club!