Brahms’ First Serenade

(Duration: 17 min)

The great love of Richard Wagner’s life was Cosima, the illegitimate daughter of Franz Liszt and his longtime mistress. She was 24 years younger than Wagner, and they were both married to others when they met, but still they consummated their infatuation in 1864, and she gave birth to Wagner’s daughter Isolde the next year. Cosima spent long periods at Wagner’s house at Tribschen, overlooking Lake Lucerne in Switzerland, and they had three children together by the time her divorce went through in 1870, allowing them to marry a month later.

Wagner capped that momentous year with an extraordinary birthday present for his thirty-three-year-old bride. On Christmas morning (she was actually born on the 24th, but she celebrated her birthday a day later), he woke up Cosima with the sounds of a fifteen-piece chamber orchestra piled onto the staircase outside her bedroom. She described the experience in her diary:

When I woke up I heard a sound, it grew ever louder, I could no longer imagine myself in a dream, music was sounding, and what music! After it had died away Richard came in to me with the five children and put into my hands the score of his Symphonic Birthday Greeting. I was in tears, but so, too, was the whole household; Richard had set up an orchestra on the stairs and thus consecrated our Tribschen forever! The Tribschen Idyll — thus the work is called!

The title Wagner inscribed on the original score was Tribschen Idyll with Fidi-Birdsong and Orange Sunrise, presented as a symphonic birthday greeting to his Cosima by her Richard. “Fidi-Birdsong and Orange Sunrise” were references to the sights and sounds Wagner remembered from the early morning birth of their son Siegfried, nicknamed Fidi. The familiar title Siegfried Idyll came later, when the cash-strapped Wagner offered this private memento for publication.

The opening melody of the Siegfried Idyll comes from a sketch Wagner made in 1864, not long after he began his affair with Cosima. The same theme appears in Act III of Siegfried, sung by Brünnhilde to the words, “Eternal I was, eternal I am, eternal in sweet, Yearning bliss, yet eternal for your sake!” The Idyll also incorporates a traditional lullaby, Schlafe, Kindchen, schlaf, which Wagner transcribed in 1868. Most of the work retains a sweet, dreamy quality; it makes only one powerful surge, with triumphant music fashioned after a leitmotif associated with the title character in the opera Siegfried. A gentle version of the same Siegfried motive brings this magical Idyll to a hushed conclusion.

Aaron Grad ©2023

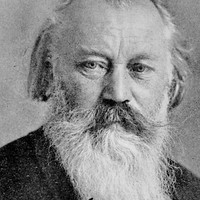

After the death of his mentor and champion Robert Schumann in 1856, Johannes Brahms did not publish any music for the next four years, and he performed only sporadically at the piano. While supporting himself by teaching and conducting, he labored over a Piano Concerto, studied counterpoint and other musical styles of the past, and challenged himself to experiment in new forms. Each year from 1857 to 1859, he spent a few months conducting a choir and offering piano lessons in Detmold, Germany, and it was there that he wrote two Serenades, using as his guide the Classical-era tradition of lighthearted music for evening gatherings. The Serenade No. 1 in D Major (1857–58) existed in a version for nine players, until Brahms expanded the scoring to chamber orchestra in 1860. The Serenade No. 2 in A Major (1858–59) also used less than a full orchestral complement, omitting violins.

The Serenades were important laboratories for Brahms. Free of the gravitas of symphonies (a form that stymied him for decades) but extending beyond the small-scale comfort zone of solo piano music and songs (genres that dominated his early output), these fruitful trials in large-ensemble writing brought forward the full potential that Schumann had seen years earlier.

Brahms almost titled the First Serenade a “Symphony-Serenade,” and without the twin scherzos inserted after the first movement and before the last, the remaining four movements do resemble the structure of a symphony. The droning start of the Allegro molto movement is unabashedly pastoral, and then the first Scherzo counters with a more urban atmosphere, combining unsettled unison lines and chains of drifting harmonies with elegant, dance-like music. The stately dotted rhythms (alternating long and short notes) of the unhurried slow movement reinforce the link to music of the past, as does the Minuet pairing with its contrast between major and minor keys. The second Scherzo returns to the sound of horn calls and rustic harmonies, setting up the Finale and its spirited new take on those lopsided dotted rhythms. This reconstruction of Brahms’ lost nonet version (completed in 1988 by Alan Boustead) brings out the individuality and intimacy of the music, in the spirit of the fun-loving serenades of yesteryear.

Aaron Grad ©2021

Get driving directions and find nearby parking.

Find dining options close to the venue.

View seating charts to find out where you'll be seating.

Get driving directions and find nearby parking.

Find dining options close to the venue.

View seating charts to find out where you'll be seating.