Mozart and the Modernists

Listen to Audio

Listen to Audio

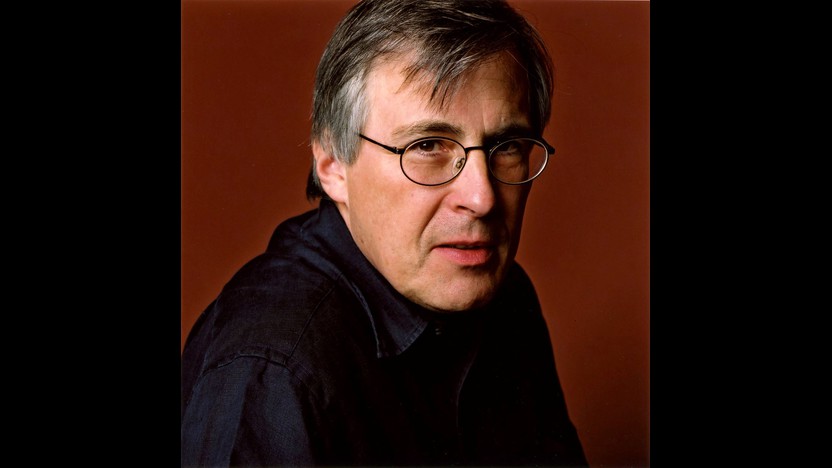

Paul Hindemith left his native Germany in 1938, after Nazi propagandists branded him a “standard-bearer of musical decay” and banned his music. After a short time in Switzerland, Hindemith moved to the United States in 1940 and secured a teaching position at Yale University, where he remained until 1953.

While in America, Hindemith reconnected with the heiress and arts patron Elizabeth Sprague Coolidge, who had commissioned the Concert Music for Piano, Brass, and Two Harps in 1930. Coolidge had funded an intimate auditorium at the Library of Congress in Washington, D.C., and the works she solicited from Bartók, Stravinsky, and others expressly for that compact stage resulted in some of the most important small-ensemble repertoire of the twentieth century. She approached Hindemith in 1944 about creating a ballet to be performed at the Coolidge Auditorium by Martha Graham; the subject was to be the Greek myth of Medea, with a detailed scenario sketched by Graham herself. Hindemith accepted the commission, but chose an entirely different subject, basing his work on a poem by Stéphane Mallarmé. The new work, Hérodiade, came together during two weeks of Hindemith’s summer vacation in New Haven, Connecticut. Graham and another member of her company gave the debut performance on October 30, 1944, on the same program that introduced Aaron Copland’s Appalachian Spring.

Mallarmé worked on the unfinished poem Hérodiade around 1864. The portion of the text that inspired Hindemith’s score takes the form of a dialogue between Herodias and her nurse. Historically, Herodias was the queen of Galilee in the first century A.D., and the mother of Salome (who, in some accounts, shares the name Herodias). The mother and daughter are infamous for their role in the execution of John the Baptist, a drama that formed the basis of Oscar Wilde’s Salome and the Richard Strauss opera of the same name. Mallarmé, for his part, described the title character of Hérodiade as neither a literal representation of Herodias or Salome but rather “a purely imaginary creature entirely independent of history.”

Hindemith’s use of text in Hérodiade was unusual in that he set the poetry to music, syllable-for-syllable, using purely instrumental forces to create an “orchestral recitation.” A note accompanying the score explains that this approach “would free the composer from the limitations of the human voice without renouncing its power of declamation and articulation.” The note goes on to explain the link between the musical technique and the poetic style:

"The melodies could be colored in ever changing tints, and the entire range from the double bass’ lowest tones to the flute’s highest could be used. Such a many-sided expansion of musical melody, although lacking the human directness of vocal expression but adorned with the polished and brittle artificiality of instrumental motion, would it not be the adequate means of accompanying Mallarmé’s wonderfully exalted but likewise polished, brittle and artificial creation?"

Hérodiade consists of eleven short movements, grouped into four main sections separated by short pauses. According to the publisher’s program note, “The Nurse is characterized by a soft tune in the string instruments while Hérodiade’s extremely erratic, expressive and symbolistic sentences are given to all the instruments, either in soloistic or ensemble form.”

Aaron Grad ©2014

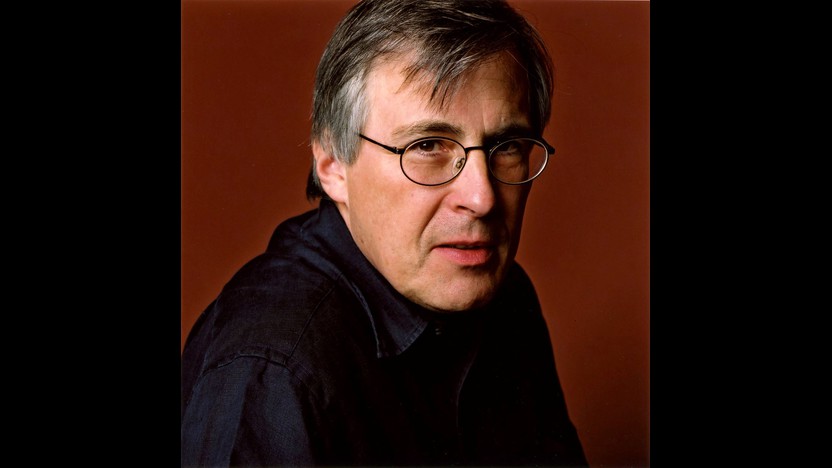

Leaving behind the security of a steady (and stifling) position in his hometown of Salzburg, Mozart arrived in Vienna in 1781 to try his luck as a freelance musician. One way he generated income was by producing concerts and selling subscriptions; it was on these popular concerts that he introduced many of his compositions involving piano, including eleven new piano concertos completed in just 25 months, between February 1784 and March 1786. In the realm of opera, Mozart happily broke a four-year dry spell when he introduced The Marriage of Figaro on May 1, 1786. These years also saw Mozart’s increasing involvement in the realm of music composed expressly for publishing, including a commission for three piano quartets initiated by Franz Anton Hoffmeister in 1785.

Mozart’s first piano quartet for Hoffmeister, the work in G minor cataloged as K. 478, missed the mark; publications of such compositions were marketed toward amateur players for home use, and Mozart’s score was far too demanding. Hoffmeister canceled the contract, but Mozart still completed a second quartet in E-flat, written in the weeks after the Figaro premiere. He may have used it for one of his own concerts—possibly in a private performance in Prague in 1787, judging from a letter he wrote—and he was able to convince the rival publisher Artaria to release the quartet later that year.

The intensity of the E-flat Piano Quartet suggests that it would not have fared any better with amateurs than its G-minor predecessor. The piano writing in the Allegro first movement is full of surging octaves patterns in the left hand and running sixteenth-notes in the right, exhibiting a level of showmanship not far off from Mozart’s piano concertos from the same period. The Larghetto second movement opens up more melodic independence for the three strings as they trade leisurely phrases with the piano. The piano takes back the starring role in the Allegretto finale, but the strings have their fun, too, as in the copycat exchanges between the piano and violin.

Aaron Grad ©2014

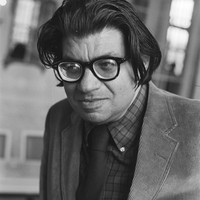

Charles Ives, who trained as a composer at Yale, resigned from his post as a church organist in 1902 and embraced the professional path of an insurance man. In the following decades he amassed a fortune, composed on evenings and weekends, and developed a singular body of music, much of which spent decades on shelves before finally reaching the public.

Some of the material included in Three Places in New England may have originated as early as 1903. Ives developed the work as a set of three movements, each based on a particular location, and he completed a version for full orchestra in 1914. The score languished for fifteen years, by which point Ives had come to the attention of Henry Cowell, a younger American composer sympathetic to Ives’s maverick tendencies. Cowell persuaded the conductor Nicolas Slonimsky, head of the Boston Chamber Orchestra, to program something by the unknown “amateur” composer from Danbury, Connecticut. Upon Slonimsky’s invitation, Ives undertook a revision of Three Places in New England in 1929, reducing the instrumentation to a chamber orchestra and condensing some of the musical ideas. Slonimsky conducted the first public performance in 1931, at a concert in New York’s Town Hall financed by Ives himself.

Ives titled the first movement The “St. Gaudens” in Boston Common (Col. Shaw and his Colored Regiment), a reference to the monument by Augustus Saint-Gaudens in Boston’s oldest park. The bronze relief sculpture depicts Colonel Robert Gould Shaw on horseback, leading the Massachusetts 54th Regiment—the first African-American regiment in the Union army, which suffered heavy losses (including the death of Shaw) while fighting near Charleston, South Carolina, in 1863. In the score, Ives prefaced the movement with a verse that he wrote:

<div style="margin-left: 1em;"> Moving—Marching—Faces of Souls!<br> Marked with generations of pain,<br> Part-freers of a Destiny,<br> Slowly, restlessly—swaying us on with you<br> Towards other Freedom!<br> The man on horseback, carved from<br> A native quarry of the world Liberty<br> And from what your country has made.<br> You images of a Divine Law<br> Carved in the shadow of a saddened heart—<br> Never light abandoned—<br> Of an age and of a nation.<br> Above and beyond that compelling mass<br> Rises the drum-beat of the common-heart<br> In the silence of a strange and<br> Sounding afterglow<br> Moving—Marching—Faces of Souls!<br> </div><br>

After the hushed reverence of the first movement, the second barrels forth with all the raucous energy of a country marching band, not unlike those led by Ives’s father decades earlier in Danbury. (This music is in fact derived from an earlier composition titled Country Band March.) Putnam’s Camp, Redding, Connecticut pays tribute to the site of a Revolutionary War encampment set up by General Israel Putnam, and it showcases Ives’s penchant for collage-like quotations from well-known tunes, including “Yankee Doodle” and “The Star-Spangled Banner.” Ives supplied a detailed program for this movement:

<div style="margin-left: 1em;">Once upon a ‘4 July,’ some time ago, so the story goes, a child went here on a picnic, held under the auspices of the first Church and the Village Cornet Band. Wandering away from the rest of the children past the camp ground into the woods, he hopes to catch a glimpse of some of the old soldiers. As he rests on the hillside of laurels and hickories the tunes of the band and the songs of the children grow fainter and fainter;—when— ‘mirabile dictu’—over the trees on the crest of the hill he sees a tall woman standing. She reminds him of a picture he has of the Goddess Liberty,—but the face is sorrowful—she is pleading with the soldiers not to forget their ‘cause’ and the great sacrifices they have made for it. But they march out of camp with fife and drum to a popular tune of the day. Suddenly, a new national note is heard. Putnam is coming over the hills from the center,—the soldiers turn back and cheer. The little boy awakes, he hears the children's songs and runs down past the monument to ‘listen to the band’ and join in the games and dances.</div><br>

The third movement, The Housatonic at Stockbridge, was inspired by a walk Ives took with his wife, Harmony, on their honeymoon in the Berkshires in 1908. Ives borrowed the movement title from a poem by Robert Underwood Johnson, and he included these excerpts from Johnson’s text as an epigraph:

<div style="margin-left: 1em;"> Contented river! In thy dreamy realm—<br> The cloudy willow and the plumy elm . . . <br> Thou hast grown human laboring with men <br> At wheel and spindle; sorrow doest thou ken; . . . <br> Thou beautiful! From every dream hill <br> What eye but wanders with thee at thy will, <br> Imagining thy silver course unseen <br> Conveyed by two attendant streams of green. . . <br> Contented river! And yet over-shy <br> To mask thy beauty from the eager eye; <br> Hast thou a thought to hide from field and town? <br> In some deep current of the sunlit brown <br> Art thou disquieted—still uncontent <br> With praise from thy Homeric bard, who lent <br> The world the placidness thou gavest him? <br> Thee Bryant loved when life was at its brim; . . . <br> Ah! There's a restive ripple, and the swift <br> Red leaves—September's firstlings—faster drift; <br> Wouldst thou away, dear stream? Come, whisper near! <br> I also of such resting have a fear; <br> Let me tomorrow thy companion be, <br> By fall and shallow to the adventurous sea! <br><br>

Aaron Grad ©2013

Get driving directions and find nearby parking.

Find dining options close to the venue.

View seating charts to find out where you'll be seating.

Get driving directions and find nearby parking.

Find dining options close to the venue.

View seating charts to find out where you'll be seating.