Mozart's Clarinet Concerto

Sponsored By

- November 11, 2015

- November 12, 2015

Sponsored By

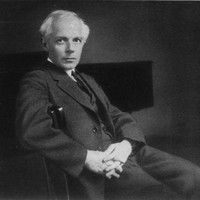

As a student at the Budapest Academy in his native Hungary, Bartok was educated in mainstream German and Austrian styles, and he graduated in 1903 writing music heavily influenced by Wagner and Strauss. The next year, while at a resort in what is now Slovakia, Bartok was so captivated by the singing he overheard from a Transylvanian-born maid that it launched him on one of the central pursuits of his life: to record and transcribe as many regional folksongs as he could find. Bartok became a pioneering scholar in the field of ethnomusicology, and over time he supervised the collection of some 14,000 distinct melodies, many of which he recorded himself using primitive wax cylinders.

In works like the Romanian Folk Dances from 1915, Bartok did not try to sanitize the authentic folk melodies by adding generic Western harmonies, nor did he pretend that his transcriptions for concert instruments would precisely recreate the nuanced inflections he captured on recording. Instead he developed a personal approach to these folksong arrangements that wrapped them in sparse and surprising accompaniments, blurring the line between composition and arrangement.

— © Aaron Grad

Aaron Grad ©2019

(Duration: 30 min)

The music that Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart wrote for his friend Anton Stadler, a clarinetist and fellow freemason, was instrumental in establishing the clarinet as an equal to its older cousins in the woodwind family. Mozart’s first composition for Stadler was the “Kegelstatt” Trio from 1786, scored for clarinet, viola and piano. (Mozart played the viola part himself.) Next came a quintet for clarinet, two violins, viola and cello, completed in 1789. This work required a basset clarinet in the key of A, an instrument with a low-range extension designed by Stadler. Mozart went on to write Stadler a concerto featuring the same instrument, completed two months before the composer’s untimely death.

The Clarinet Concerto in A Major demonstrates Mozart’s keen understanding of the solo instrument’s range and agility. The tonal quality of the clarinet changes through its range, from the deep resonance of the bass notes, through the warm and hollow midrange of the chalumeau register, and up into the brilliant clarity of the highest octaves. At certain points in the fast opening movement, the soloist seems to play several opera characters engaged in dialogue, leaping from range to range; other times, a single scale or arpeggio journeys across all four octaves of the instrument’s compass.

In 1785, a critic wrote of Anton Stadler, “One would never have thought that a clarinet could imitate the human voice to such perfection.” Judging by the slow movement penned expressly for Stadler, Mozart surely agreed!

The finale has a bit of Haydn’s sense of humor in it, as in the playful held notes of the main theme that draw out unresolved tension. The episodic structure of the Rondo allows for fanciful and dramatic excursions, making each return to the familiar music all the more delightful.

Aaron Grad ©2023

Watch Video

Watch Video

“How fickle my plans are,” Pyotr Tchaikovsky wrote, “whenever I decide to devote a long time to rest!” Tchaikovsky’s time with his sister in Ukraine turned into a working vacation that summer of 1880, as he confided to his patron, Nadezdha von Meck. “I had just begun to spend a series of entirely idle days, when there came over me a vague feeling of discomfort and real sickness; I could not sleep and suffered from fatigue and weakness. Today I could not resist sitting down to plan my next symphony — and immediately I became well and calm and full of courage.”

Tchaikovsky’s plan for that music wavered between a symphony and a string quartet, until he landed on something in between: a serenade for string orchestra. The title and form of the work paid homage to Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, the greatest composer of serenades, whom Tchaikovsky once praised as “the culminating point which beauty has reached in the sphere of music.”

The Serenade for Strings merges a Classical sense of order with Tchaikovsky’s own abundant gift for melodic expression. Despite the modest heading that promises a “Piece in the form of a Sonatina,” the first movement establishes a grand and noble tone with a reverent chorale. Instead of a minuet or scherzo, the second movement offers a flirtatious diversion in the form of a Waltz. The slow movement, labeled an Elegy, takes a more somber turn. In the finale, the “Russian theme” promised by the subtitle is an amalgamation of folk material that Tchaikovsky harvested from a printed collection.

Aaron Grad ©2021

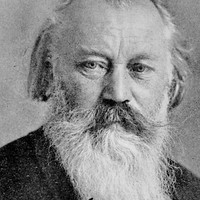

Brahms completed his set of 21 Hungarian Dances in 1869. Originally for piano duet, these lively dance tunes are among his most popular works. They have been arranged for a wide variety of instruments and ensembles; Brahms himself provided orchestrations for some of the dances and other composers have followed his example, including Dvořák. Goran Fröst’s present arrangement with solo clarinet seems especially appropriate because the instrument has always played a pivotal role in Central and East European folk bands. It is worth noting that Brahms became exceptionally fond of the clarinet and at the end of his life was captivated by the playing of the Meiningen clarinetist Richard Mühlfeld, for whom he wrote four glorious and highly influential chamber works.

Professor Colin Lawson ©

The winter of 1848-49 was a prolific period for Schumann following some years of poor mental health, which had made composing difficult in the extreme. Among the works that poured forth was a series of pieces for small chamber ensembles, including duos with piano that variously featured oboe, clarinet, horn and cello. The five little pieces for cello and piano were created by Schumann to sound folk-like, simple and immediately accessible. In transferring the original delicate textures to a much larger ensemble, Rolf Martinsson has closely adhered to the style of Schumann’s own orchestral writing. His transparent orchestral balance ensures that the clarinet soloist is never overwhelmed and he achieves further variety by sharing the main melodic material with both flutes and violins. Rolf Martinsson’s arrangement of the Schumann cello pieces was prompted by a conversation with Martin Fröst following their collaboration on his clarinet concerto Concert Fantastique, Opus 86 (2010).

Professor Colin Lawson ©

Listen to Audio

Listen to Audio

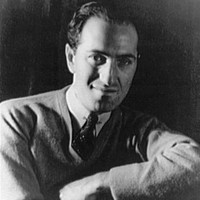

George Gershwin was eleven when his family first brought a piano into their apartment. Four years later, after some lessons in classical repertoire including Chopin and Debussy, Gershwin dropped out of high school and found work as a “song plugger” on Tin Pan Alley, New York’s row of music publishing firms. He began to write his own songs, signed on with a publisher, and gravitated toward Broadway, finding work as a rehearsal pianist on a Jerome Kern show. Gershwin’s first Broadway production opened in 1919, and the influential performer Al Jolson added Gershwin’s “Swanee” to a revue that year. Jolson’s recording of “Swanee” sold millions of copies in 1920 and put Gershwin on the map as a top songwriter. Still Gershwin never stopped stretching himself in his unfairly short life; he did not settle into the breezy patchwork style of Rhapsody in Blue, written at age 25, nor simply churn out hit Broadway tunes like the many he co-wrote with his lyricist brother, Ira.

The last musical Gershwin completed was Shall We Dance, a 1937 film starring Fred Astaire and Ginger Rogers. With Astaire playing a famous ballet dancer whose real love was jazz, the score led Gershwin to create some of his most sophisticated hybrids of classical and jazz styles. The flirtatious Promenade, affectionately known as Walking the Dog, features a solo clarinet (a part written for jazz bandleader Jimmy Dorsey) inserting “blue notes” and other sassy inflections. In the movie, this music accompanies a wordless scene in which the prim and disinterested Ginger Rogers walks her dog on the deck of a cruise ship; Astaire’s character bribes his way to borrowing a dog just so he can stroll alongside her.

Aaron Grad ©2017

Please note that these performances will take place on Wednesday and Thursday at 7:30pm due to tour scheduling, but are part of the Friday and Saturday evening Ordway series.

PLEASE NOTE: The program for our November 11 and 12 concerts has changed. Artistic Partner Martin Fröst—who was scheduled to premiere his Genesis project with the SPCO—has withdrawn from all upcoming engagements through December due to Meniere’s Disease, a disorder of the inner ear which causes severe vertigo, sickness, and tinnitus. He sends his sincerest regrets, and we look forward to welcoming him back this spring when he has fully recovered. Fröst's absence necessitates a change to the concert's repertoire, and the new program will now feature clarinetist Alexander Fiterstein. Please see above for updated programming.

Get driving directions and find nearby parking.

Find dining options close to the venue.

View seating charts to find out where you'll be seating.

SPCO concerts are made possible by audience contributions.

For exclusive discounts, behind-the-scenes info, and more:

Sign up for our email club!