Musician Appreciation Concert

Sponsored By

Sponsored By

Listen to Audio

Listen to Audio

The Marriage of Figaro was the first of Mozart’s three collaborations with the Italian librettist Lorenzo da Ponte, who also scripted Don Giovanni and Così fan tutte. It was possibly Mozart’s idea to borrow the scenario from a 1778 French play by Pierre Beaumarchais, a sequel to his earlier hit, The Barber of Seville (later immortalized in Rossini’s 1816 opera). The farce was banned in Vienna at the time for its sarcastic condemnation of the aristocracy, and da Ponte had to scrub the work of its political overtones to gain the emperor’s approval.

The Marriage of Figaro transpires over the course of “one crazy day.” Figaro, the head servant to Count Almaviva, is due to wed the maid Susanna, who meanwhile has been subjected to the Count’s lecherous advances. In the end, the Count gets his comeuppance, and Figaro and Susanna marry. Although the music of the overture has no major presence later in the opera, it sets the scene for the hilarity that ensues. The overture’s form is quite lean, with neither a repeat of the exposition nor a development section. The frenetic Presto tempo and persistent eighth-notes give the prelude a breathless feeling throughout its four-minute sprint, while rising figures and drawn-out crescendos establish the buoyant tone of the opera.

Aaron Grad ©2013

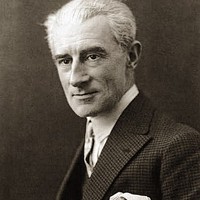

Maurice Ravel, meticulous yet hot-headed, took after both of his parents, a Swiss engineer and a Basque peasant. Even though he was raised in Paris, Ravel was a perennial outsider who got himself expelled from the Paris Conservatory once as a piano student in 1895, and then again in 1900 after he returned as a composer and wouldn’t follow the rules for writing a proper fugue. His five consecutive rejections in the prestigious Rome Prize competition became something of a public scandal, and even his own teacher, Gabriel Fauré, piled on when he labeled Ravel’s final submission “a failure.” The submitted piece was none other than the String Quartet in F Major, which has long since taken its rightful place as a cornerstone of the quartet repertoire.

One musician who recognized the power of Ravel’s quartet was Claude Debussy, who wrote to his younger colleague, “In the name of the gods of music and in my own, do not touch a single note you have written in your Quartet.” Ravel’s quartet in fact shares many traits with Debussy’s own string quartet from a decade earlier, in the way they both develop thematic connections that link the separate movements.

In the famous second movement of Ravel’s quartet, the main melody is a close kin of the first movement’s opening theme. Here the material takes on a Spanish flair with strummed textures and moody scales related to Flamenco music, showing off Ravel’s deep connection to his mother’s roots. This fiery material gets refracted through Ravel’s fastidious sense of form, taking on the quality that led Stravinsky to offer a famously backhanded compliment, calling Ravel “the most perfect of Swiss watchmakers.” The Orpheus Chamber Orchestra commissioned this ensemble arrangement by Michi Wiancko.

Aaron Grad ©2025

Listen to Audio

Listen to Audio

When Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart began writing symphonies, he was an eight-year-old keyboard prodigy in London, where he had played for King George III and befriended Johann Christian Bach — the youngest son of Johann Sebastian Bach, and a trendsetter in the emerging genre of the symphony. Mozart’s earliest symphonies naturally followed the bright and clean style mastered by the “London” Bach. Later, as a teenager back in his hometown of Salzburg, Mozart looked to the example of Joseph Haydn, whose brother happened to work alongside Mozart and his father. Some of the symphonies Mozart wrote as a seventeen- and eighteen-year-old ranked among his first truly brilliant compositions, and by that time he had already completed three-fourths of his lifetime symphonic output.

Mozart had fewer occasions to write symphonies during his heyday as a busy freelancer in Vienna. He might never have written his three final symphonies were it not for the money troubles that plagued his final years, a period when demand for his performances had dried up. Some opportunity must have sparked this symphonic trilogy (a detail historians have not managed to unearth), but most likely nothing came of it. Mozart may not even have heard all three before he died.

Mozart’s final symphony, completed on August 10, 1788, has long been known as the Jupiter Symphony, a moniker probably added by Johann Peter Salomon, the same shrewd impresario who later brought Franz Joseph Haydn to London. The opening movement, set in an energized Allegro vivace tempo, establishes a ceremonial atmosphere with an abundance of quick, stepwise swoops. The Andante cantabile slow movement follows with serene and spacious music, in which ample rests and breaks leave melodies unaccompanied, downbeats unstressed, and textures uncluttered.

Like in the symphonies by his friend Haydn, the minuet functions as a light-hearted palate cleanser. The main “joke” here comes in the form of phrases that slip down through segments of the chromatic scale, touching on notes that momentarily clash with the home key.

The finale introduces a number of related themes and then juggles them with a variety of contrapuntal techniques. This balancing act reaches its climax in the coda, which contains a swirling fugue treatment of all five main themes at once. It proves how well Mozart absorbed the techniques of Johann Sebastian Bach, at a time when most composers dismissed such formal counterpoint as hopelessly old-fashioned, and it affirms Mozart’s godlike talent for marrying intellectual clarity with earth-shaking emotion.

Aaron Grad ©2022

This special concert is a fundraising event and is not eligible for ticket exchanges or guest pass redemption. Additional restrictions may apply.

Can't attend, but still want to support the musicians of the SPCO? You can make a gift directly. All proceeds from this fundraising event will go to SPCO musicians in appreciation for the passion, dedication and incredible artistry they share every year. Make your gift today.

Event Packages

Ticket packages are also available for purchase. To reserve a Gold or Silver event package, please contact Erin VanBurkleo at 651.292.3275 or evanburkleo@spcomail.org.

Gold – $10,000 (includes 12 premium tickets)

Silver – $5,000 (includes 6 premium tickets)

Note: Your ticket purchase total minus $25 per ticket is tax-deductible to the extent allowed by law. Please note that it is our policy that donations made to this event are non-refundable.

What portion of my ticket purchase is tax deductible?

The fair market value of each ticket is $25; that means the remaining amount of the purchase price for each ticket to this special event is a donation to the musicians of the SPCO. Example: An SPCO fan purchases a premium ticket for $1,000. $975 of the purchase price is a tax-deductible donation; the remaining $25 is the cost of admission. Please note that it is our policy that donations made to this event are non-refundable.

What happens to my ticket(s) if I can no longer attend?

Please contact the Ticket Office to turn back your tickets as a tax-deductible donation to the musicians of the SPCO or request a refund. This concert is a special fundraising event, so tickets cannot be exchanged from this event into another performance. The Ticket Office can be reached by phone Monday through Friday 12pm–5pm at 651.291.1144 or by email at tickets@spcomail.org.

Get driving directions and find nearby parking.

Find dining options close to the venue.

View seating charts to find out where you'll be seating.

SPCO concerts are made possible by audience contributions.

For exclusive discounts, behind-the-scenes info, and more:

Sign up for our email club!