Opening Weekend: Beethoven’s Seventh Symphony

After achieving international notoriety with The Rite of Spring, the ballet which garnered him a reputation for breaking artistic boundaries, Igor Stravinsky began composing in a more reserved neoclassical style. His first major neoclassical work was the ballet Pulcinella, which premiered in May 1920 at the Paris Opera. The suite you will hear today includes musical selections from the ballet and was first performed by the Boston Symphony Orchestra in 1922.

Stravinsky wrote:

“Pulcinella was my discovery of the past, the epiphany through which the whole of my late work became possible. It was a backward look, of course — the first of many love affairs in that direction — but it was a look in the mirror, too.”

Based on the eighteenth-century play Quatre Polichinelles semblables, the ballet Pulcinella was an artistic collaboration between Stravinsky (music), Pablo Picasso (stage design and costumes), Léonide Massine (choreography) and Sergei Diaghilev (impresario). Pulcinella is a stock comedic character who featured prominently in Neapolitan puppetry beginning in the 1620s. He is often portrayed as a cunning thief with very specific physical features, including a hunched back, a crooked nose, thin legs, a large belly, full cheeks, and a wide mouth. Pulcinella generally strives to rise above his social station, and he is often involved in schemes that save other characters.

Stravinsky’s ballet depicts a witty scene in which Pulcinella’s friends Florindo and Cloviello are unsuccessfully attempting to win the affections of Prudenza and Rosetta. Much to the chagrin of Pulcinella’s girlfriend Pimpinella, Rosetta coyly kisses Pulcinella. Meanwhile, Florindo and Cloviello are jealous of Pulcinella’s ability to have two women interested in him, and they beat him up and appear to stab him. The stabbing, however, is a farce intended to make Pimpinella forgive Pulcinella for his indiscretion. After Pulcinella is “resurrected” by another friend dressed as a magician, Pimpinella marries Pulcinella, and Florindo and Cloviello ride into the sunset with Prudenza and Rosetta.

Stravinsky’s score for Pulcinella borrowed musical elements from existing eighteenth-century compositions that were believed to have been composed by Giovanni Battista Pergolesi. Musicologists have since discovered that the music Stravinsky utilized was actually by several composers, including Pergolesi, Domenico Gallo, Carlo Ignazio Monza, Count Unico Wilhelm van Wassenaer and Alessandro Parisotti.

In some instances, Stravinsky merely borrows clusters of intervals, and in others, he uses entire melodic themes and harmonic progressions from the eighteenth-century sources. Stravinsky’s music for Pulcinella, therefore, is both pastiche and parody, and the work functions as a unique type of musical criticism. In his book The Stravinsky Legacy, Jonathan Cross aptly challenges the listener to question “whether what Stravinsky did [in Pulcinella] was mere critique…or whether he was able to make the material ‘transcend itself.’”

Paula Maust ©2022

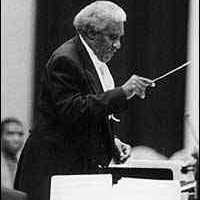

American composer Coleridge-Taylor Perkinson earned B.M. and M.M. degrees in composition from the Manhattan School of Music in the 1950s, a time of great division within the field of American classical music. Proponents of extreme experimentalism dismissed the tastes of the listening public and endeavored to keep the discipline of classical music composition strictly within the academy. This perspective was clearly outlined in essays such as Milton Babbitt’s “Who cares if you listen?”

At the same time, however, the works of canonical Western classical composers, such as Ludwig van Beethoven and Johannes Brahms, were becoming further cemented into the standard concert repertory. Popular works by composers such as Sergei Rachmaninov and Samuel Barber were also gradually making their way into a canon of classical music aimed at pleasing the general public.

Perkinson’s multi-faceted musical career expanded beyond these conflicting viewpoints and encompassed a vast array of classical, jazz, dance, pop, film and television music. Although he was on the composition faculty at Brooklyn College for several years, Perkinson ultimately gravitated to professional opportunities with a wider public reach. He was, for example, a co-founder and director of the Symphony of the New World and worked as the music director for the American Theater Lab and the Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater.

Perkinson’s mother was an accomplished musician, and she named her son after the influential Black British composer Samuel Coleridge-Taylor (1875-1912). Sinfonietta No. 1 was written in 1954, when Perkinson was just twenty-two years old. The piece is a fusion of influences from eighteenth-century counterpoint, nineteenth-century American romanticism, blues and spirituals. The Largo “Song Form” is the second of three movements and features carefully controlled dissonances and soaring lyrical melodies.

Paula Maust ©2022

Watch Video

Watch Video

Western classical music is frequently tied to politics, as was the case with Ludwig van Beethoven and several of his symphonies. Most noteworthy, perhaps, was Beethoven’s dedication of his third symphony to Napoleon, which the composer erased upon learning that Napoleon had declared himself emperor. Beethoven’s Symphony No. 7 is also often interpreted as a musical confrontation with Napoleon, whose troops had recently occupied Vienna.

Beethoven composed Symphony No. 7 between 1811 and 1812, at the same time Napoleon was planning his campaign against Russia. The piece was dedicated to Count Moritz von Fries, an Austrian patron of the arts, and the Russian Empress Elisabeth Aleksiev. In December 1813, Beethoven conducted the premiere at the University of Vienna. The event was a charity concert for soldiers wounded in the Battle of Hanau, and Beethoven remarked at the concert’s opening that “we are moved by nothing but pure patriotism.”

The first movement of Symphony No. 7 begins with a long, slow introduction composed of ascending scales. This introduction transitions to the Vivace section through a series of sixty-one repetitions of the pitch E. Dance-like rhythms permeate the entire symphony, including the first theme of the Vivace section. The last few minutes of the movement feature a coda, which contains a remarkable passage of a two-measure motive that is repeated ten times in a row. This repeated motive occurs at the same time as the other instruments play a four-octave pedal point on the pitch E.

So popular that it was encored at the premiere, the second movement of Symphony No. 7 is often performed today as a stand-alone piece. The movement is in ternary form, or three large sections. The first and third sections are composed of similar thematic material and feature a repeated ostinato pattern of a quarter note, two eighth notes, and two quarter notes. These two sections are in the key of A minor, and Beethoven demonstrates his skill with imitative counterpoint in the third section, which is structured as a fugato. The contrasting middle section in A major contains a warm melody in the clarinets, which is accompanied by triplets in the violins.

A scherzo is a musical joke in which humor is created through compositional devices such as unequal phrase structures, disjunct rhythms, alternating meters and unexpected harmonies. Beethoven employs most of these techniques in the third movement of Symphony No. 7, which is divided into five large sections alternating ABABA. The A sections are rhythmically vigorous and composed of jagged, irregular phrases. The B sections contain quotations of the Austrian pilgrims’ hymn.

Symphony No. 7 closes with a movement full of fiery, relentless passion and perpetual motion. The first theme of the movement is a modified version of the instrumental ritornello to Beethoven’s own arrangement of the Irish folk song “Save me from the grave and wise.” Symphony No. 7 was regarded by Beethoven as one of his best compositions, and a newspaper account of an early performance recalled that the “applause rose to the point of ecstasy.”

Paula Maust ©2022

Get driving directions and find nearby parking.

Find dining options close to the venue.

View seating charts to find out where you'll be seating.

SPCO concerts are made possible by audience contributions.

For exclusive discounts, behind-the-scenes info, and more:

Sign up for our email club!