Schubert's Fifth Symphony

Sponsored By

- May 21, 2015

- May 22, 2015

- May 23, 2015

Sponsored By

Bach likely composed his two extant violin concertos around 1730, not long after he agreed to lead Leipzig’s Collegium Musicum, founded in 1702 by a young Telemann. This talented amateur group gave weekly performances, often in the informal atmosphere of a coffeehouse, providing Bach a sociable venue for secular music.

Bach crafted his violin concertos using the ritornello structure popularized by Italians (especially Vivaldi) in which a main theme returns multiple times to punctuate the form. The essential theme of the first movement of the Violin Concerto No. 1 in A Minor emphasizes pairs of rising notes, first making a bold leap up the interval of a fourth, and then returning for a narrow rise of a half-step.

So much of the emotional tension in the Andante slow movement occurs in the simple but profound bass line: its steady pulses, its hopeful ascents, and its many long silences that leave the soloist with only the fragile support of violins and violas. The rolling triplet pulse of the Allegro assai finale is akin to the gigue (or, as it called in the British isles, the jig), the dance style that ends many of Bach’s instrumental suites.

Aaron Grad ©2016

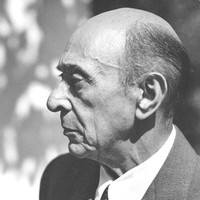

Before Arnold Schoenberg became the teacher and trendsetter at the center of the “Second Viennese School” of composers who explored the wilds of atonality, he was a self-taught amateur steeped in the luxurious Romanticism of Franz Liszt and Richard Strauss. The closest he came to having a composition teacher was through his friendship with Alexander von Zemlinsky, and it was during their vacation together in 1899 that Transfigured Night emerged from three swift weeks of work.

Schoenberg’s great innovation in Transfigured Night was to apply the idea of program music, as found in the tone poems of Liszt and Strauss, to a chamber ensemble. Schoenberg’s original scoring for two violins, two violas and two cellos matched a format pioneered by Johannes Brahms, in whose hands the string sextet became a vehicle for pure chamber music with a Classical orientation. Instead of the usual abstract movements, Schoenberg created one continuous score in five sections, following the shape of the poem "Verklärte Nacht (Transfigured Night)" by Richard Dehmel, about a forlorn couple that, while walking on a moonlit night, works through the revelation that her pregnancy resulted from an affair.

The musical storytelling relies on the skillful manipulation of tonal harmony over the course of one long journey from minor to major. Supported by a nervous drone, the first section sets the course by plodding down the minor scale in lopsided, dotted rhythms. This stepping pattern becomes a familiar point of reference, returning in different forms to remind us of the couple and their fateful walk together.

The second section, beginning with an unexpected major chord, corresponds to the second stanza of the poem, in which the woman “confesses a sin to the man at her side: she is with child and he is not its father.” The music becomes agitated, smeared with rising chromatics, until the third section intervenes with music of a simpler and more somber character, linked to the section of the poem in which “she staggers onward.”

The third section ends on a minor chord, setting up the crucial moment: With a decisive pivot to a major chord, a cello melody gives voice to the man’s wish that his companion should “not burden her soul with thoughts of guilt.” A lustrous violin solo brightens the night, just as “the moon’s sheen enwraps the universe.”

The final section forms a tranquil coda in D major, basking in love’s warmth that “will transfigure the little stranger.” The stepping theme returns with new optimism, and shimmering arpeggios offer a parting view of “wondrous moonlight.”

Aaron Grad ©2021

Watch Video

Watch Video

Schubert enjoyed a childhood rich with music—singing in the court choir, playing string quartets with his family, and participating in the school orchestra—but he only began composing around the age of twelve or thirteen. Like his father and brothers, he trained as a teacher, and at seventeen he began working as a teaching assistant at an elite Viennese school, while also keeping up twice-weekly composition lessons with the local Kapellmeister, Antonio Salieri.

Schubert’s accomplishments in the next two years must rank as the greatest growth spurt in musical history: he composed some 300 songs, plus four symphonies, three masses, five musical dramas, three string quartets, three violin sonatas and dozens of other works. This flurry all came before Schubert reached his twentieth birthday, while he was working full-time, and before the Viennese public had seen or heard a single note of his music.

HAYDN-ERA ORCHESTRATION Schubert completed the Symphony in B-flat Major on October 3, 1816. Aside from a private reading that fall, the symphony sat dormant until long after his death; the first public performance came in 1841, and the score was not published until 1885. Of all of Schubert’s symphonies, finished and unfinished, this is the only one that omits clarinets, trumpets and timpani from the orchestration, essentially turning back the clock to the symphonic customs of the 1780s. (Haydn composed 15 symphonies between 1781 and 1786 with instrumentation identical to Schubert’s, while Mozart used the same array for the first version of his Symphony No. 40, in 1788.) Schubert’s crisp musical material matches the economical scoring, with a first theme built out of a two-measure cell, and a second theme that incorporates the same distinctive rhythm from the earlier motive.

The slow movement becomes more expansive in its melodies, and a contrasting section that moves to a surprising key has Schubert’s clear stamp, with singing themes set over pulsing accompaniments, as found in many of his songs. The Menuetto is quick and boisterous enough to qualify as a scherzo, Beethoven’s rowdy answer to Haydn’s more polite minuets, while the key of G minor recalls Mozart’s stormy Symphony No. 40. The finale closes the symphony on a lively note, honoring Schubert’s debt to the masters of the previous generation.

Aaron Grad ©2016

Tickets to these concerts are currently only available for season ticket holders. Season ticket packages start at just $30 and subscribing gives you access to priority seating, free exchanges and more! Become a subscriber now. Individual tickets to performances will go on sale in late August.

Get driving directions and find nearby parking.

Find dining options close to the venue.

View seating charts to find out where you'll be seating.

SPCO concerts are made possible by audience contributions.

For exclusive discounts, behind-the-scenes info, and more:

Sign up for our email club!