Tchaikovsky's Serenade for Strings

The German-born George Frideric Handel found his greatest fame in England, but he got there by first mastering Italian opera. After working for the opera orchestra in Hamburg, Germany, he left for Italy to learn firsthand from the trendsetting composers in Rome, Florence and other musical hotspots, until he capitalized on his relationship with the royal House of Hanover (Germans who would come to rule England, starting with King George I) to write and present Italian operas in London. Handel’s shrewd business sense matched his brilliance as a composer, and he always knew how to give audiences what they wanted — even if it required recycling his greatest hits or “borrowing” liberally from his competitors.

In the case of the six concerti grossi published as Handel’s Opus 3 in 1734, any blame for shady behavior seems to belong to John Walsh, Handel’s London publisher who went behind the composer’s back to capitalize on the popularity of the concerto grosso style perfected by Arcangelo Corelli. The mishmash of scores that Walsh pulled together dated back decades, representing a range of styles and formats, and it even included selections that Handel didn’t write.

The essence of the concerto grosso format is to have a small group of solo instruments working in concert with a larger ensemble, usually consisting of strings and basso continuo—the semi-improvised, Baroque equivalent of a jazz “rhythm section” that anchors the bass line and fills in the harmonies. In the Concerto Grosso in B-flat Major printed first within Opus 3, the biggest mystery is why it never returns to the listed home key, instead staying in G-minor for the latter two movements. (A manuscript of the concerto in this same form predates Walsh’s publication by at least a decade, so in this case we can’t blame him for tinkering.) Oboes and violin take the starring role in the outer movements, with bassoons jumping in during the finale with some virtuosic solo turns of their own. It might seem incongruous that two flutes (originally recorders) only participate in the solemn slow movement that hints at a French style, but in Handel’s day woodwind players were expected to be generalists, and so those parts could have been played by the otherwise unoccupied second oboe and bassoon.

Aaron Grad ©2022

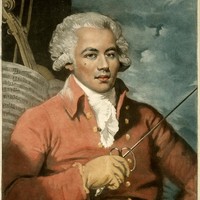

Joseph Bologne, Chevalier de Saint-Georges, was a champion fencer before his twentieth birthday. He was also a renowned boxer, dancer, and marksman, but his real love was music, and his prowess with the violin allowed him to become the leader of a powerhouse orchestra in Paris and a personal instructor to Marie Antoinette. She nominated him to become music director of the Paris Opera in 1776, but the prejudices he had transcended up to that point finally proved to be too strong: the prima donnas at the opera refused to sing for a mixed-race maestro.

Bologne’s French father owned sugar plantations on the Caribbean island of Guadeloupe, and the son that he raised as his own was conceived with one of the African women he enslaved. Throughout his life, Bologne defied what should have been possible for a person of African descent under France’s Code Noir, and his determination to become an opera composer proved to be another hurdle that he cleared with gusto. He staged his comic opera L’amant anonyme at a duke’s private theater in 1780, and he also published the opera’s three-part overture as his Symphony in D Major (Op. 11, No. 2). The overture’s exuberant energy and singing melodies make it clear why Bologne has so often been called the “Black Mozart” — even though it was the young Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart who picked up important ideas during his time in Paris from watching the Chevalier in action, and not the other way around.

Aaron Grad ©2021

In its original form, Umoja, the Swahili word for unity and the first principle of the African Diaspora holiday Kwanzaa, was composed as a simple song for women's choir. It embodied a sense of 'tribal unity,' through the feel of a drum circle, the sharing of history through traditional “call and response” form and the repetition of a memorable sing-song melody. It was rearranged into woodwind quintet form during the genesis of Coleman’s chamber music ensemble, Imani Winds, with the intent of providing an anthem that celebrated the diverse heritages of the ensemble itself.

Almost two decades later from the original, the orchestral version brings an expansion and sophistication to the short and sweet melody, beginning with sustained ethereal passages that float and shift from a bowed vibraphone, supporting the introduction of the melody by solo violin. Here, the melody is sweetly singing in its simplest form with an earnestness reminiscent of Appalachian style music. From there, the melody dances and weaves throughout the instrument families, interrupted by dissonant viewpoints led by the brass and percussion sections, which represent the clash of injustices, racism and hate of the world today. Spiky textures turn into an aggressive exchange between upper woodwinds and percussion, before a return to the melody as a gentle reminder of kindness and humanity. Through the brass led ensemble tutti, the journey ends with a bold call of unity that harkens back to the original anthem. Umoja has seen the creation of many versions, that are like siblings to one another, similar in many ways, but each with a unique voice that is informed by Coleman’s ever evolving creativity and perspective.

“This version honors the simple melody that ever was, but is now a full exploration into the meaning of freedom and unity. Now more than ever, Umoja has to ring as a strong and beautiful anthem for the world we live in today,” says Coleman.

VColeman Music Publishing, LLC ©2019

Listen to Audio

Listen to Audio

“How fickle my plans are,” Pyotr Tchaikovsky wrote, “whenever I decide to devote a long time to rest!” Tchaikovsky’s time with his sister in Ukraine turned into a working vacation that summer of 1880, as he confided to his patron, Nadezdha von Meck. “I had just begun to spend a series of entirely idle days, when there came over me a vague feeling of discomfort and real sickness; I could not sleep and suffered from fatigue and weakness. Today I could not resist sitting down to plan my next symphony — and immediately I became well and calm and full of courage.”

Tchaikovsky’s plan for that music wavered between a symphony and a string quartet, until he landed on something in between: a serenade for string orchestra. The title and form of the work paid homage to Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, the greatest composer of serenades, whom Tchaikovsky once praised as “the culminating point which beauty has reached in the sphere of music.”

The Serenade for Strings merges a Classical sense of order with Tchaikovsky’s own abundant gift for melodic expression. Despite the modest heading that promises a “Piece in the form of a Sonatina,” the first movement establishes a grand and noble tone with a reverent chorale. Instead of a minuet or scherzo, the second movement offers a flirtatious diversion in the form of a Waltz. The slow movement, labeled an Elegy, takes a more somber turn. In the finale, the “Russian theme” promised by the subtitle is an amalgamation of folk material that Tchaikovsky harvested from a printed collection.

Aaron Grad ©2021

All audience members are required to present proof of full COVID-19 vaccination or a negative COVID-19 test within 72 hours prior to attending this event. Masks are required regardless of vaccination status. More Information

Concerts are currently limited to 50% capacity to allow for distancing. Tickets are available by price scale, and specific seats will be assigned and delivered a couple of weeks prior to each concert — including Print At Home tickets. Please email us at tickets@spcomail.org if you have any seating preferences or accessibility needs. Seating and price scale charts for the Ordway Concert Hall can be found at thespco.org/venues.

Get driving directions and find nearby parking.

Find dining options close to the venue.

View seating charts to find out where you'll be seating.

SPCO concerts are made possible by audience contributions.

For exclusive discounts, behind-the-scenes info, and more:

Sign up for our email club!