Viennese Masters

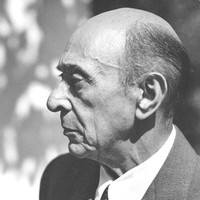

Audience members who start to squirm as soon as they notice the name Arnold Schoenberg on the program need not fear the Ten Early Waltzes for Strings. Schoenberg was well aware of his dubious reputation when he commented, “If people speak of me, they at once connect me with horror, with atonality, and with composition with twelve tones. Generally it is always forgotten that before I developed these new techniques, there were two or three periods in which I had to acquire the technical armament that enabled me to stand distinctly on my own feet….”

The Ten Early Waltzes were apparently written in 1897, before Schoenberg’s twenty-third birthday, and they represent his earliest period, when his models were the masters of Viennese classicism and he was enamored of Brahms. He had only recently dedicated himself to a musical career. His mother, like so many parents then and now, worried that he would never make a living in music, so she found him a position as a bank clerk. It didn’t last very long, though. According to Schoenberg’s sister, the director of the bank urged their mother to allow her brother to become a musician: he was of little use to the bank since he covered all of his paperwork with music. To earn a living he conducted workers’ choruses and orchestrated operettas, and he expanded his musical horizons through acquaintanceships with fellow musicians. Notable among these was Alexander Zemlinsky, who had founded the musical association Polyhymnia in 1895, the same year that Schoenberg left the bank to embark on a musical career. Zemlinsky described the Polyhymnia orchestra as “not large: a couple of violins, one viola, one cello, and one double bass. We were young and thirsting for music, and we met once a week to play…. At the one desk of cellos sat a young man who mistreated his instrument, playing with more fire than accuracy…. This cellist was none other than Arnold Schoenberg.” At their second public concert, on March 2, 1896, Polyhymnia performed Schoenberg’s Notturno for solo violin, harp, and strings alongside works by Bach, Boccherini, Grieg, and Zemlinsky. It was probably with this chamber orchestra in mind that Schoenberg composed his waltzes for strings, or rather, began composing them. After completing ten he started an eleventh but stopped after only eight bars. Who knows how many more he might have written had a performance opportunity materialized? We have no evidence that they were played by Polyhymnia or any other ensemble during Schoenberg’s lifetime. The first performance of the ten completed waltzes was at the Schönberg-Haus in Mödling, a Vienna suburb, on May 1, 2003.

It should not be surprising that a Vienna-born composer like Schoenberg would be drawn to the waltz throughout his life—he composed the Alliance-Walzer for piano when he was eight and nearly 65 years later used waltz fragments in his String Trio—but his model for these early waltzes was not the waltzes of the Strauss family, but rather those of Brahms, with perhaps some hints of Dvořák.

David Grayson ©2013

The Three Sketches originated in a request by the violinist Thomas Zehetmair for an encore piece to follow the performances of the Mozart Sinfonia concertante, K. 364, that he planned to give with his wife and duo partner, the violist Ruth Killius, in celebration of the 250th anniversary of Mozart’s birth. The resulting triptych is more a companion piece than an encore, and in these performances it is performed before, rather than after the Mozart work. To give more brilliance to the viola part in his Sinfonia concertante, Mozart specified that all four strings should be tuned in scordatura, a half step higher than usual. (“Scordatura” is the Italian word for “mistuning.”) Holliger adopted the same viola scordatura for his Three Sketches as the viola would need to be “mistuned” for the Mozart. He completed the set in September 2006, and the duo gave the first performance on June 22, 2007, at the Aldeburgh Festival in England. The score is dedicated to “Ruth and Thomas.”

In his preface to the score, Holliger commented that he “was fascinated by the unforeseen possibilities of two instruments with different tuning and [I] sketched out three totally different pieces.” He described the first, Pirouettes harmoniques, as “a quasi-ballet of weightless, graceful dancers—but depicted exclusively by natural harmonics.” Quarter tones add to the atmospherics.

In the second sketch, Danse dense, the instruments are muted. It is “an incredibly fast perpetuum mobile: closely interlocking, irregularly articulated rhythmic patterns are superimposed or follow one another to form a wild and extremely intense dance.”

The third, Cantique à six voix, is “a calm piece in the style of organum, which is literally a final song: the performers each play a two-voice instrumental part and sing an extra part, producing six-part harmony,” with the wordless vocal parts blending completely with the instrumental sonorities. The range of the vocal parts is based on the gender of the dedicatees—a male violinist and a female violist—although the score allows for other distributions by permitting the players to transpose up or down an octave any notes that lie outside their range or, in the case of a male violist, to sing falsetto.

On his publisher’s website, Holliger offers the following epigram: “My entire relation to music is such that I always try to go to the limits.”

David Grayson ©2013

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, the onetime child prodigy who had dazzled audiences all over Europe, found himself in an unexpected predicament in his early twenties: he was stuck in his hometown of Salzburg. He resigned from the court of the local Archbishop in 1777 and set out with his mother in search of new employment, but his visits to Mannheim and Paris failed to produce any real prospects. At least he came away from his time in Mannheim, home to one of the world’s finest orchestras, with a new arsenal of brilliant ensemble effects.

Mozart returned to Salzburg in 1779 and begrudgingly resumed working for the Archbishop. On the side, he cultivated his own private circle of musicians and patrons, for whom he wrote symphonies, concertos, serenades, and other entertaining diversions. We don’t know exactly the circumstances that led to Mozart composing the Sinfonia concertante for violin and viola in 1779, but we can presume that it was some social event in Salzburg. Mozart, a fine violinist and violist, would surely have played one of the solo parts.

The idea of a concerto for multiple soloists had been around for nearly a century (in the form of the concerto grosso), but the sinfonia concertante was a trendy new approach flourishing in places like London, Mannheim, and Paris — where Mozart actually wrote his first example for a quartet of soloists. In the Sinfonia concertante for violin and viola, Mozart addressed the natural imbalance in projection by calling for the viola to be tuned a half-step higher than normal, increasing the alto instrument’s power. (Modern instruments and metal strings have alleviated this need, so today’s soloists often forgo the transposition.)

One of the sounds Mozart picked up in Mannheim was a long crescendo that gathers strength over a constant bass note, a device so characteristic of the local composers that it was dubbed the “Mannheim roller.” A terrific example is the final climax of the tutti exposition that precedes the arrival of the soloists.

The central Adagio movement unwinds its haunting main theme in skeins of long, singing phrases that weave between the two solo instruments. As in the first movement, the two soloists share a fully composed cadenza, imparting a chamber-music intimacy to this orchestral score. The finale continues the impressive display of ensemble colors, including prominent passages for the horns and oboes, all in support of quick-witted banter between the soloists.

Aaron Grad ©2024

Get driving directions and find nearby parking.

Find dining options close to the venue.

View seating charts to find out where you'll be seating.

Get driving directions and find nearby parking.

Find dining options close to the venue.

View seating charts to find out where you'll be seating.