Welcome Patricia Kopatchinskaja, Part 2

Mozart’s Adagio and Fugue began life as the Fugue in C minor for two keyboards. Composed in 1783, that work (to which Mozart would add the Adagio introduction when preparing the string arrangement) appeared as part of a flurry of new pieces produced upon Mozart’s arrival in Vienna in 1781. Mozart’s productivity during these years knew no limits. Between 1781 and 1785, he completed numerous piano concerti and symphonies; important chamber works including violin sonatas, the Quintet for Piano and Winds, K. 452, and the six “Haydn” Quartets; the Mass in C minor; and the operas Die Entführung aus dem Serail and Le nozze di Figaro.

The string quartet version of the Adagio and Fugue came about under less than auspicious circumstances. By the late 1780s, Mozart’s popularity—and, consequently, his income—had taken a downward turn. Although Le nozze had been acclaimed in Prague, its Vienna premiere was received poorly. The following year, Don Giovanni likewise failed to please: It was criticized as being overly learned, too sophisticated for the general listener. In order to generate much-needed income in the summer of 1788, Mozart composed at a furious pace, completing a symphony, violin sonata, piano trio, piano sonata, and this arrangement of the Fugue for piano duo, with the added Adagio introduction, in the span of only a few weeks. (The work is frequently heard today, as on this evening’s program, played by string orchestra.)

The work’s character is unrelentingly severe. The opening dialogue between cellos and upper strings establishes a majestic rhythmic feel. Using an uncompromising pattern that continues for the rest of the introduction, Mozart intersperses music that serves to contrast the aggressive opening measures. This material—as mysterious as the opening is obvious—infuses the Adagio with an ominous atmosphere. It is Mozart the opera composer at work: introducing a shady character who puts everyone en garde. As the stentorian sections remain the same length, the shadowy phrases grow longer, leaving the Adagio in a mood of great tension and anticipation.

The cellos again have the first say as the angular fugue subject breaks in. As in his quartet arrangements of Bach’s Well-Tempered Clavier, Mozart, still under the Baroque master’s spell, demonstrates here a complete mastery of fugal technique. The Fugue serves simultaneously as an homage to Bach and as an announcement to the Viennese musical community of the arrival of a singular compositional voice.

Patrick Castillo ©2014

For violinist Patricia Kopatchinskaja’s debut performances with the SPCO, she collaborated with her parents, Viktor Kopatchinsky and Emilia Kopatchinskaja, and SPCO Principal Bass Zachary Cohen in performing folk music selections from her native Moldova in Eastern Europe. Viktor Kopatchinsky is a master of the cimbalom, a type of hammered dulcimer, and Emilia Koptachinskaja is a folk violinist/violist and improviser. This selection, called Căluşarii, refers to a Moldovan secret society whose origins date from at least the 17th century. In more recent times, the Căluşarii became known for their highly energetic dancing and fiddling and would often take part in village festivals in the weeks after Easter.

© Kyu-Young Kim

Kyu-Young Kim ©2021

Watch Video

Watch Video

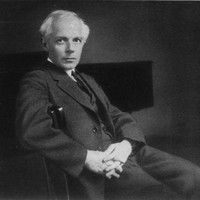

As a student at the Budapest Academy in his native Hungary, Bartok was educated in mainstream German and Austrian styles, and he graduated in 1903 writing music heavily influenced by Wagner and Strauss. The next year, while at a resort in what is now Slovakia, Bartok was so captivated by the singing he overheard from a Transylvanian-born maid that it launched him on one of the central pursuits of his life: to record and transcribe as many regional folksongs as he could find. Bartok became a pioneering scholar in the field of ethnomusicology, and over time he supervised the collection of some 14,000 distinct melodies, many of which he recorded himself using primitive wax cylinders.

In works like the Romanian Folk Dances from 1915, Bartok did not try to sanitize the authentic folk melodies by adding generic Western harmonies, nor did he pretend that his transcriptions for concert instruments would precisely recreate the nuanced inflections he captured on recording. Instead he developed a personal approach to these folksong arrangements that wrapped them in sparse and surprising accompaniments, blurring the line between composition and arrangement.

— © Aaron Grad

Aaron Grad ©2019

In the middle of the 14th century, the Bubonic plague, also known as the Black Death, eradicated half of the population in Europe. From about this time, there appeared representations of the "Dance of Death", often on the walls of churches or in cemeteries, of a human being meeting and dancing with a personification of death. The message that death touches us all, no matter what station of life, was portrayed through a series of pictures that reflected the hierarchy of society, starting with the pope, and then going down from emperor, cardinal, king, clergyman, young man, maiden, child and so on. Very often the individual pictures were accompanied by short verses in four lines, and as a rule, the human being says something to death and then death responds. These verses often included some humor or even social criticism.

The poem "Der Tod und das Mädchen" (1785) by Matthias Claudius (1740-1815) is clearly an emanation of this medieval tradition. It even takes over the form of the ancient verses with a dialogue between victim and death.

Das Mädchen: Vorüber! Ach, vorüber! Geh, wilder Knochenmann! Ich bin noch jung! Geh, lieber, Und rühre mich nicht an. Und rühre mich nicht an.

Der Tod: Gib deine Hand, du schön und zart Gebild! Bin Freund, und komme nicht, zu strafen. Sei gutes Muts! ich bin nicht wild, Sollst sanft in meinen Armen schlafen!

The Maiden: Pass me by! Oh, pass me by! Go, fierce man of bones! I am still young! Go, my dear, And do not touch me. And do not touch me.

Death: Give me your hand, you beautiful and tender form! I am a friend, and come not to punish. Be of good cheer! I am not fierce, Softly shall you sleep in my arms!

Such consoling and even seducing words will still give chilling shivers, coming from a skeleton that will take you to your grave.

Franz Schubert set this poem to music in his Lied, "Der Tod und das Mädchen" (1817). After the agitated and rhythmically irregular exclamation by the terrorized maiden, the rhythm becomes that of a solemn Pavan just in the moment when she calls him "dear". The Pavan, a dignified and formal Renaissance dance, was often danced by the king and was also used in music of mourning. In the context of Schubert’s Lied, the Pavan rhythm expresses the sovereign power of death over the surrendering human creature.

This same material reappears in Franz Schubert’s Quartet No.14 in D Minor, Death and the Maiden (1824). The variations of the slow movement explore different facets of the Pavan part of the Lied: anxiety, menace and anger. The variation with the solo cello can be understood as the tender seduction of a shy virgin.

The first movement however takes up the atmosphere of the agitated first part of the Lied; terror strikes from the first beat, death appears from nowhere and repeated triplets put everything into excited doubt.

The Scherzo can then be seen as the death dance. The trio, however, is a caressing, even erotic waltz, where the girl maybe still feels sad longings for life. Or is the longing already for death? During the repetition of the Scherzo, the maiden surrenders to the increasingly violent dance.

The final movement is a furious, unreal and ghastly tarantella leading into another world.

Schubert wrote this quartet in a very difficult time. The failure of his operas, his poverty, his miserable and declining state of health, the absence of his best friends and the anguish of disappointed love drove him to despair. In a letter to his friend Leopold Kupelwieser, he wrote:

"I feel myself the most unhappy, most wretched being in the world…'My peace is gone, my heart is heavy; I shall find it never, and never more;' I can say daily, for every night when I go to sleep, I hope that I may never wake again, and every morning renews the grief of yesterday..."

Clearly we have here the idea of death as friend and redeemer.

To open our ears to this musical exploration, we have included a prelude and interludes between each of the Schubert movements. We begin with a meditation: an ancient Byzantine chant of Psalm 140 (“Lord, I have cried unto thee, hear me”). Of course, we have to include Schubert’s original song, here in an arrangement by Michi Wiancko. We echo the Pavan in Schubert’s 2nd movement with one of John Dowland's Pavanes from Seaven Teares. Before the Finale, we refresh our ears with unsettling works by one of the greatest living composers, György Kurtág. This project with the SPCO has enlarged our dimensions of hearing and together we approached the music as a soloist would, individually, but all souls mystically linked to an intuitive whole that does not need a conductor

Patricia Kopatchinskaja ©2016

Get driving directions and find nearby parking.

Find dining options close to the venue.

View seating charts to find out where you'll be seating.

Get driving directions and find nearby parking.

Find dining options close to the venue.

View seating charts to find out where you'll be seating.