Yeol Eum Son Plays Beethoven’s Second Piano Concerto

(Duration: 7 min)

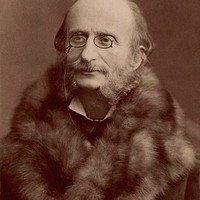

Richard Wagner and Johannes Brahms may have been the most revered and influential composers of their time within elite circles, but if you had asked any average Joe in Europe who wrote the most popular music for the stage and concert hall, the two names on their tongue would have been Johann Strauss II and Jacques Offenbach. Born into a German family originating from the city that shares their surname, young Jacob Offenbach started going by Jacques when he resettled in Paris as a teenager. He left the Paris Conservatory after a year to play cello in the opera house that produced comedies, and in the decades to come he would specialize in those whimsical operettas that drew adoring crowds the way musicals do today.

Offenbach also kept up a recital career on the cello, and he bolstered his repertoire with the exquisitely tuneful Les larmes de Jacqueline (Jacqueline’s Tears) in 1853 as the second in a set of three “Woodland Harmonies.” Long a favorite of cellists, it reached new heights of popularity when the superstar cellist Jacqueline du Pré made it a signature piece.

Aaron Grad ©2023

Listen to Audio

Listen to Audio

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart delighted his fans in Vienna by introducing a dozen new piano concertos between 1784 and 1786, and he might have kept up that pace if a war with the Ottoman Empire hadn’t scattered the aristocrats who subscribed to those concerts. He entered the Piano Concerto No. 23 in A Major into his catalog of completed compositions on March 2, 1786, and he probably debuted it on one of the three programs he presented that spring.

Preliminary sketches, which may date from as early as 1784, included a pair of oboes in the instrumentation, but the final version substituted clarinets instead. The concerto’s first movement gives the woodwinds far more attention than they would have been accustomed to at that time, starting with unaccompanied phrases in the orchestra’s introductory tutti and continuing in the conversational development section.

Later editions notched the tempo of the middle movement up to Andante, but Mozart’s manuscript for this heavy-hearted movement clearly calls for the slower and more affecting Adagio tempo. Again the woodwinds play an outsized role in accompanying and answering the piano, and they also introduce the only wholly cheerful passage in the movement, in the contrasting major key. Minor-key episodes within the rondo finale rehash some of the angst of the slow movement, but the main recurring theme always reaffirms the jovial home key with its definitive leaps.

Aaron Grad ©2024

(Duration: 28 min)

When the 21-year-old Ludwig van Beethoven arrived in Vienna in 1792, he was following in the footsteps of his hero Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, whose death a year earlier left an opening for a hotshot keyboard player that the young Beethoven eagerly filled. In those early years, before his reputation earned him a measure of artistic independence (and before his deafness cut him off from the world), Beethoven hustled for all sorts of paying gigs around town — teaching lessons, performing public and private concerts and writing accessible music that could be published and sold to amateurs. And just as Mozart wowed Vienna with self-produced concerts centered on a stream of new piano concertos, Beethoven took up the concerto as an ideal vehicle for self-promotion.

The earliest piano concerto that Beethoven completed was this one in B-flat, although it became known as No. 2, since the later C-major concerto was published first. Initial sketches of the B-flat concerto date back as far as 1788, when Beethoven was still a teenage viola player in the court orchestra in his hometown of Bonn, and then he reworked it substantially in 1794 to prepare for his first Mozart-style concert the following spring. Beethoven made additional revisions in 1798, and a decade later he wrote out cadenzas, for the benefit of other performers less gifted than he was in the art of improvisation.

Demonstrating just how well Beethoven had internalized the refined craft of Mozart and Franz Joseph Haydn, this concerto’s opening measures exhibit textbook contrast and balance between the two offsetting phrases. The first is loud, rhythmically robust, scored for the whole orchestra, and in the home key of B-flat; the second is soft, rhythmically smooth, scored just for strings, and in the contrasting key of F. These motives develop through a high-energy movement of brilliant piano figurations, surprising harmonic shifts, and galloping rhythms. With the insertion of the cadenza that Beethoven added in the heart of his “middle period,” stark counterpoint and insistent rhythmic repetitions introduce an extra note of firmness and drama.

The central Adagio, after elaborating a gentle theme, adds its most striking detail at the point when the cadenza would normally appear. Instead of inserting a virtuosic flourish, Beethoven gives the soloist a single melodic line to convey “with great expression,” alternating with comments from the orchestra as the movement draws to a close. The Rondo finale especially benefited from the 1798 revision, which transformed the square rhythm of the original main theme to the punchy, syncopated motive we know today.

Aaron Grad ©2023

Get driving directions and find nearby parking.

Find dining options close to the venue.

View seating charts to find out where you'll be seating.

Get driving directions and find nearby parking.

Find dining options close to the venue.

View seating charts to find out where you'll be seating.