Ballard, Bruce and Dvořák

(Duration: 11 min)

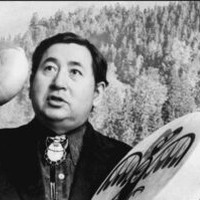

Louis Ballard’s father came from the Cherokee Nation and his mother the Quapaw Nation; he grew up within her culture in the northeast corner of Oklahoma, speaking the Quapaw language and receiving the name Honganozhe, meaning “One who Stands with Eagles.” His education included stints at one of the boarding schools that have become notorious for their mission of coerced assimilation, and eventually a pursuit of Western music that led to degrees from the University of Tulsa. All the while he stayed connected to his ancestral music and culture, and he took inspiration from Béla Bartók’s synthesis of folk music and art music to compose some of the first compositions that incorporated authentic elements of Native music — as opposed to the whitewashed “Indian” tunes and rhythms that had been simplified and circulated among white composers since Antonín Dvořák’s time.

In 1969, a commission from the Dorian Woodwind Quintet (funded by the Rockefeller Foundation) led Ballard to compose Ritmo Indio. The score went on to win the Marian Nevins MacDowell Award, a high honor named for one of American’s great arts patrons. Ballard’s central place in the intersection of Native and concert music also led to his appointment around that time as the director of music programs for the Bureau of Indian Affairs.

Ballard’s “Study in American Indian Rhythms,” as the subtitle defines it, does not attempt to transcribe Native melodies, and even the rhythms are manipulated and filtered through Ballard’s own compositional voice. In The Source, the underlying beat remains constant, but shifting subdivisions make for a supple, unpredictable pulse. The central slow movement, The Soul, assigns the oboe player to switch to the Sioux flageolet (somewhat like a recorder) to play a free-flowing solo marked con alma, or “with soul.” The Dance volleys between two-beat and three-beat measures in a vigorous finale.

Aaron Grad ©2023

(Duration: 34 min)

Even though Antonín Dvořák excelled at writing the same sorts of formal chamber music as his mentor Johannes Brahms, extending the tradition that stretched back to Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart and Ludwig van Beethoven, his first real fame came from his splashy Slavonic Dances that converted Czech folk material into popular miniatures for piano or orchestra. He went on to teach at the Prague Conservatory, and his leadership there helped spawn a national school of Czech composers, distinct from the mainstream line of German and Austrian music.

It was precisely that ability to crystallize a place’s folk traditions into viable concert music that made Dvořák the ideal candidate for a new job in the New World. In 1892, he accepted a lucrative offer to direct the newly established National Conservatory in New York, with a mission to help seed an “American” school of concert music. Besides teaching a diverse cohort of American composers, Dvořák incorporated local sounds into his own music from the time.

After finishing Symphony No. 9 (“From the New World”) in May of 1893, he took his family into the heartland for an extended summer vacation in Spillville, Iowa, a small farming town populated mainly by Czech immigrants. While there, he composed his String Quartet No. 12, along with this string quintet with a second viola; both have acquired the nickname “American.”

Dvořák formed his ideas about American music from heavily edited collections of Native American songs and especially from the African American spirituals he learned from a conservatory student whose grandfather had been enslaved. One of Dvořák’s sons also recounted in his memoir how thrilled the composer had been to meet the several dozen residents of an Iroquois encampment near Spillville. Their songs and drumming had a direct and immediate impact on the musical language of the String Quintet in E-flat, joining the pentatonic modes and juxtapositions of major and minor keys that Dvořák carried over from his Slavonic approach to folk music adaptation.

Aaron Grad ©2023

(Duration: 28 min)

There is a paradox in music, and indeed all art — the fact that life-enriching art has been produced, even inspired by conditions of tragedy, brutality and oppression, a famous example being Messiaen's Quartet for the End of Time, written while he was in a prisoner of war camp. Gumboot Dancing bears this trait — it was born out of the brutal labour conditions in South Africa under Apartheid, in which Black miners were chained together and wore Gumboots (wellington boots) while they worked in the flooded gold mines, because it was cheaper for the owners to supply the boots than to drain the floodwater from the mine. Apparently, slapping the boots and chains was used by the workers as a form of communication, which was otherwise banned in the mine, and this later developed into a form of dance. If the examples of Gumboot Dancing available online are anything to go by, it is characterised by a huge vitality and zest for life. So this for me is a striking example of how something beautiful and life-enhancing can come out of something far more negative. Of course, this paradox has a far simpler explanation — the resilience of the human spirit.

My Gumboots is in two parts of roughly equal length, the first is tender and slow moving, at times 'yearning'; at times seemingly expressing a kind of tranquility and inner peace. The second is a complete contrast, consisting of five, ever-more-lively 'gumboot dances', often joyful and always vital.

However, although there are some African music influences in the music, I don't see the piece as being specifically 'about' the Gumboot dancers, if anything it could be seen as an abstract celebration of the rejuvenating power of dance, moving as it does from introspection through to celebration. I would like to think, however, that the emotional journey of the piece, and specifically the complete contrast between the two halves will force the listener to conjecture some kind of external 'meaning' to the music — the tenderness of the first half should 'haunt' us as we enjoy the bustle of the second; that bustle itself should force us to question or reevaluate the tranquility of the first half. But to impose a meaning beyond that would be stepping on dangerous ground — the fact is you will choose your own meaning, and hear your own story, whether I want you to or not.

David Bruce ©2008

Get driving directions and find nearby parking.

Find dining options close to the venue.

View seating charts to find out where you'll be seating.

Get driving directions and find nearby parking.

Find dining options close to the venue.

View seating charts to find out where you'll be seating.