Beethoven/5: Jonathan Biss Plays Beethoven’s Fourth Piano Concerto

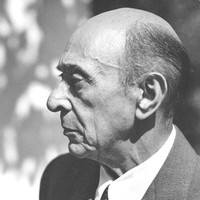

Arnold Schoenberg is most famous — or perhaps infamous — for pioneering atonality and the twelve-tone method of composition. Despite all the “accusations of anarchy and revolution” directed his way over the years, his own view (as he explained in a 1949 lecture) was that his development as a composer “was distinctly evolution, no more exorbitant than that which always has occurred in the history of music.”

The Chamber Symphony No. 2 came from a major inflection point in Schoenberg’s evolution. He started it in 1906 on the heels of the First Chamber Symphony, a hyper-dense score that pushed the logic of tonality to its breaking point. While midstream on the Second Chamber Symphony, he began experimenting with a new way of approaching his craft in other works, developing a style that drifted away from tonal rules toward a free atonality, guided by his own intuition. He tried picking the Chamber Symphony back up in 1911 and 1916, but the gap between his old and new working methods left him at an impasse.

Schoenberg evolved even further in the 1920s with his twelve-tone system, and with the rise of the Nazis in the 1930s, the Jewish composer went into exile, settling in Los Angeles. With some prodding by Fritz Stiedry, another Austrian expatriate who led an orchestra in New York, Schoenberg took up the Second Chamber Symphony once more, 33 years after he began it. He wrote to Stiedry, “I have been working on the second chamber symphony for a month now. I spend most of the time trying to discover ‘What did the author mean here?’ My style has now become very consolidated and it is now effortful to unify what I wrote down back then, justifiably trusting in my feeling for form, with my current extensive requirements for ‘visible logic.’”

Schoenberg only made minor changes in the Adagio first movement, adjusting some of the accompanying textures and adding twenty new measures at the end. The fiery second movement, on the other hand, required about half new material, including a final, epilogue-like section. The total effect is remarkably cohesive for a score assembled at opposite ends of Schoenberg’s continual evolution as a composer.

Aaron Grad ©2024

Non un concerto di suoni, bensì di risonanze più o meno lontane. Il solista si sottrae, nega la sua abituale supremazia, per riaffermarla su altri livelli. Non sembri questa un'idea strana, poiché sfiora e dichiara l'essenza trascendente del linguaggio/pensiero. In quanto strumento di conoscenza l'arte ci può trasformare. Così scrivevo anni addietro: "la musica è emanazione e ornamento del silenzio. La trasfigurazione sonora, l'avvicinarsi all'indistinto genera inquietudine: il non saper distinguere fra presenza e assenza." L'inquietudine dell'apprendimento è essenziale per la scoperta dell'universo, che di tutti noi è genitore.

Not a concerto of sounds, but of resonances, near and distant. The soloist withdraws, denies his usual superiority, to reaffirm it on other levels. This does not seem to be a strange idea, for it touches upon and speaks to the transcendent essence of language/thought. As an instrument of consciousness, art can transform us. As I wrote years ago: “Music is the emanation and ornamentation of silence. The transfiguration of sound, the approach of the obscure, causes anxiety: that of not knowing how to distinguish between presence and absence.” The anxiety of learning is essential for the discovery of the universe, which is parent to us all.

Translation by The Cleveland Orchestra

Salvatore Sciarrino ©2017

Watch Video

Watch Video

On December 22, 1808, Beethoven presented a remarkable concert in Vienna. The four-hour extravaganza featured the public debuts of the Fifth and Sixth Symphonies, the Fourth Piano Concerto and the Choral Fantasy (composed as a showstopper for the occasion), as well as miscellaneous excerpts from the Mass in C, a rendition of the concert aria Ah! Perfido and some piano improvisations. Reports from the concert bemoaned the glut of music, the hall’s frigid temperature and a sloppy orchestra; the Choral Fantasy actually ground to a complete halt, at which point Beethoven returned to the beginning and prolonged the concert even further.

The Fourth Piano Concerto left spectators particularly baffled, and the work remained largely untouched until Felix Mendelssohn revived it in 1836. The mystery begins when the piano enters alone, spinning out a simple harmonic progression marked piano dolce (quiet and sweet). Then, after the piano leaves a chord hanging that by all expectations would resolve back to a stable point of arrival, the soloist withdraws and the strings enter in a totally foreign and exotic new key. Unexpected harmonic transitions continue to crop up throughout the first movement, keeping with the quizzical mood established at the outset.

In the central Andante con moto, a single line, scored across several octaves in the strings, engages the piano in a halting tête-à-tête in E minor. The final cadence flows directly to the Rondo finale, which again starts with just a whisper. The strings take the lingering memory of the pitch E as the start of the galloping tune, stating the theme first and then passing it to the piano. The melody begins with a repeated tone and an ascending arpeggio that anchors our ears in C major—except the actual destination of this concerto is to return to its starting key of G major. Amazingly, this main theme of the finale never begins in the “proper” key, even when it appears moments from the end, adding to the sense of sleight-of-hand that defines this most elusive of Beethoven’s piano concertos.

— © Aaron Grad

Aaron Grad ©2017

Get driving directions and find nearby parking.

Find dining options close to the venue.

View seating charts to find out where you'll be seating.

Get driving directions and find nearby parking.

Find dining options close to the venue.

View seating charts to find out where you'll be seating.