Dvořák in America

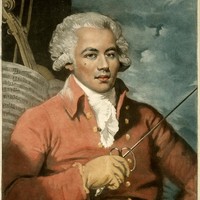

The French composer and violinist Joseph Bologne, Chevalier de Saint-Georges, casts an intriguing figure in the annals of Western music history. Born in Guadeloupe (a French territory in the West Indies) to a gentleman and his African slave, Saint-Georges is considered the first classical composer of African ancestry. Though little-known today, he enjoyed considerable renown—musical and otherwise—in his lifetime: his Two Violin Concerti, Opus 2, with which he made his public debut as a violinist, suggest that he was an elite virtuoso. He was also a champion fencer and, by contemporary accounts, a romantically prodigious Don Juan as well.

While racial prejudice certainly impacted his career (most notably when a group of prominent divas petitioned against his appointment as music director of the Paris Opéra, entreating Marie Antoinette that it would “degrad[e] their honour and delicate conscience [to have] them submit to the orders of a mulatto”), Saint-Georges nevertheless made his living successfully as a musician. He produced a sizeable oeuvre of violin concerti, symphonies concertantes, and operas, and was founding music director of the Concert de la Loge Olympique, for which ensemble he commissioned Haydn to compose his Paris Symphonies.

The possibly spurious Symphony in G Major is the first of two published together as Saint-Georges’s Opus 11. It is an innocuous thing, an example of the style galant that came into vogue in the latter half of the eighteenth century: inoffensive melodies supported by light accompaniments. (Saith Voltaire, “Being galant, in general, means seeking to please.”)

The Symphony comprises three movements. The opening Allegro’s principal theme consists of little more than ascending and descending arpeggios; the flowing second theme provides modest textural contrast, but primarily serves to reinforce the music’s galant demeanor. The genteel Andante is equally affable. The buoyant finale provides the Symphony’s most satisfying music, marked by contrapuntal string textures and colorful deployment of oboes and horns.

Patrick Castillo ©2016

The scoring of Mozart’s Serenade for Winds in C Minor, K. 388—pairs of oboes, clarinets, bassoons, and horns—suggests that it was designed to serve as a festive piece, for use at some civic, probably outdoor, celebration. This would seem at odds, however, with the music’s gravitas: set in the stormy key of C minor, and comprising musical ideas of unsmiling severity. (Mozart would rework the Serenade in 1788 as the String Quintet in C Minor, K. 406.)

The opening Allegro’s first theme reveals Mozart to be an irrepressible font of melodic invention—a direct forebear, in this regard, to the following century’s “King of Song,” Franz Schubert. Following a dour unison statement, the theme spins forth a series of short melodic utterances, each of a distinct character, but which complement one another in seamless fashion: from plaintive, to aggressive, to coquettish in rapid succession, before the theme’s eloquent closing phrase.

The Andante responds to the first movement’s Sturm und Drang (“Storm and Stress”) with effortless melody set to transparent harmonies and delicate, featherweight textures. This is music that sits easily alongside Mozart’s most inspired slow movements.

The Menuetto is the Serenade’s most obviously festive feature. Yet even here, the music’s character is more angular, a bit surlier, than Mozart’s listeners might have expected from a wind band playing a genteel dance form. The minuet is a straightforward canon (think “Row, row, row your boat”). Mozart gets craftier for the contrasting Trio section, spinning a double canon in inversion: the second oboe presents the melody, taken up two measures later by the first oboe, but up a fourth and inverted (i.e., turned upside-down). Two measures later, the first bassoon repeats the second oboe melody, and the second bassoon inverts it, down a fourth.

The Serenade concludes with a set of seven variations on a beguiling theme. The most affecting of these—perhaps, indeed, one of the most exquisite passages of the entire work—is the seventh variation: a sinewy, chromatically rich transformation of the theme, which proceeds straightaway to the suddenly good-humored major-key coda.

Patrick Castillo ©2016

In 1891, Antonín Dvořák received an invitation from Jeannette Thurber, President of the newly founded National Conservatory in New York, to come to America. Dvořák had by this time achieved universal renown as the greatest champion of his native Czech music. Meanwhile, America’s nascent classical music community was experiencing an identity crisis. Young American composers studied abroad and came back writing music imitative of Brahms and Wagner. A distinctly American musical language had yet to emerge.

Enter Dvořák. On the strength of his reputation as a great nationalist composer, Dvořák was invited to serve as the National Conservatory’s Artistic Director in the hopes that he would guide America’s composers in discovering their own national language. Dvořák accepted the invitation, came to America, and studiously absorbed all that he heard: African-American spirituals, traditional Native American music, and other American folk styles of the day.

Dvořák and his family spent the summer of 1893 in Spillville, Iowa, a rural town with a large Czech community. The idyllic setting yielded two chamber works that remain among the most beloved in the repertoire: the Opus 96 String Quartet and Opus 97 String Quintet, both nicknamed American.

While a beguiling evocation of the Midwestern countryside may indeed be heard immediately from the first page of the Quartet’s score, the question has fairly been raised as to just how American the work truly is. Reflecting on his immersion in traditional American music, Dvořák ultimately conceded, “I found that the music of the negroes and of the Indians was practically identical, [and that] the music of the two races bore a remarkable similarity to the music of Scotland.” This is surely in reference to the pentatonic scale, a five-note scale characteristic of much of the world’s folk music. The American Quartet’s opening theme, introduced by the viola against a shimmering texture in the violins, dances gleefully around this scale. Likewise does the effervescent clarinet melody in the second movement of Mendelssohn’s Scottish Symphony. The joyful music that begins the scherzo is said to reflect the song of the scarlet tanager, an American songbird that Dvořák observed in Spillville—but the syncopated rhythm also recalls the Czech folk dances that infuse much of Dvořák music. The trio section slows the exuberant dance melody to a plaintive sigh, thus transforming a joyous evocation of his native Bohemia into melancholy nostalgia.

As a critic for The New York Times wrote in 1894, reviewing an early performance of both the Quartet and the Quintet, “Whatever may be the general opinion as to the Americanism of these works, … we may be thankful that Dr. Dvořák came to America if he was able to find inspiration here for such lovely compositions.”

Patrick Castillo ©2016

Trumpeter and composer Wynton Marsalis inarguably ranks among the most widely recognized and influential jazz musicians in the world today. In addition to his work as a performer, he is a gifted educator and, in his capacity as founding artistic director of Jazz at Lincoln Center, a tireless advocate for the art form (though not without controversy: Marsalis’s indifference to avant-garde styles has drawn intense criticism from such luminaries as Keith Jarrett, Cecil Taylor, and Herbie Hancock, with whom Marsalis toured and recorded early in his career).

Trained from a young age in both jazz and classical music—appearing as soloist with the New Orleans Philharmonic in Haydn’s Trumpet Concerto at the age of 14, and joining Art Blakey’s Jazz Messengers at 20, while still a student at the Juilliard School—Marsalis has continued to indulge a voracious musical appetite throughout his career. (As a performer, he contends that jazz is far more challenging to play than Baroque or Classical repertoire.) In 1984, Marsalis became the first musician to win Grammy awards in both jazz and classical recordings (for his album Think of One and a recording of trumpet concertos by Haydn, Hummel, and Leopold Mozart). Since that time, Marsalis has continued to produce concert music, film scores, ballets, et al., alongside his untiring activities as a bandleader and soloist. He has received nine Grammy Awards to date, across genres, and was awarded the 1997 Pulitzer Prize for Music for his oratorio Blood on the Fields.

Marsalis composed his String Quartet No. 1, At the Octoroon Balls, in 1995; the work was commissioned for Jazz at Lincoln Center, and was premiered later that year. The quartet was premiered by the Orion String Quartet in a joint presentation by the Chamber Music Society of Lincoln Center and Jazz at Lincoln Center.

At the Octoroon Balls is inspired by Marsalis’s upbringing in New Orleans. That city, with its rich sociocultural history and cross-pollination of musical styles—from traditional West African music and plantation songs to Western European influences—subsequently gave rise to jazz music. Marsalis’s string quartet celebrates his hometown’s unique musical dynamic with its compelling integration of classical and jazz idioms. “A ball is a ritual and a dance,” Marsalis explains. “Everybody was in their finest clothing. At the Octoroon Balls there was an interesting cross-section of life. People from different strata of society came together in pursuit of pleasure and fulfillment. The music brought people together.”

Patrick Castillo ©2016

Please note: Fanfare Pre-Concert Discussion for SATURDAY, JANUARY 28 at the Ordway has been canceled.

Get driving directions and find nearby parking.

Find dining options close to the venue.

View seating charts to find out where you'll be seating.

Get driving directions and find nearby parking.

Find dining options close to the venue.

View seating charts to find out where you'll be seating.