Faust and Fantasy

C. P. E. Bach’s Six Symphonies for String Orchestra were commissioned by a fascinating patron and man of letters: Baron Gottfried van Swieten (1733–1803). The van Swieten family was Dutch, but Gottfried spent his adolescence in Vienna, where his father was the personal physician to Empress Maria Theresa. From 1770 to 1777, van Swieten was the Dutch ambassador to the court of King Frederick II of Prussia, where C. P. E. Bach had long served as court harpsichordist. Baron van Swieten studied composition during that time with Johann Philipp Kirnberger, a former student of J. S. Bach’s. Next, the baron succeeded his late father as the Head of the Imperial Library in Vienna. At regular gatherings at his house, van Swieten arranged readings of oratorios by Handel, and he introduced his protégés—Mozart most significantly—to the fugues of Bach. He also formed a close partnership with Joseph Haydn, serving as the librettist for The Creation and The Seasons. His reach even extended to Beethoven, who dedicated his First Symphony to van Swieten in 1800. In a letter published in 1799, Baron van Swieten outlined his refined musical philosophy:

I belong, as far as music is concerned, to a generation that considered it necessary to study an art form thoroughly and systematically before attempting to practice it. I find in such a conviction food for the spirit and for the heart, and I return to it for strength every time I am oppressed by new evidence of decadence in the arts. My principal comforters at such times are Handel and the Bachs and those few great men of our own day who, taking these as their masters, follow resolutely in the same quest for greatness and truth.

Although the correspondence between C. P. E. Bach and van Swieten did not survive, a secondhand account written years later suggests that Bach was given total leeway as to the style and complexity of the commissioned sinfonias, or symphonies. The six resulting works, composed in 1773, belong to an older tradition related to Italian overtures. Instead of four independent movements, as in most of Haydn’s contemporaneous symphonies, Bach’s sinfonias for string orchestra each contain three short sections, beginning and ending in fast tempos and moving to a slow section in the middle.

The G Major Sinfonia further reveals its Italian influence in the driving figurations and string-crossing patterns of the opening section. The sudden shifts of mood and disruptive silences, though, reflect the more progressive side of Bach’s personality. The first section ends with a hanging trill that resolves into the remote key of E major to begin the Poco adagio central section. This slow music has a conversational quality, full of repartee between flirtatious violin melodies and more stern unison utterances. The final Presto section at first introduces itself as a lighthearted dance, but minor-key migrations and surprising contrasts give the closing passages a piercing expressivity that is typical of Bach’s Empfindsamer Stil, or “Sensitive Style.”

Aaron Grad ©2012

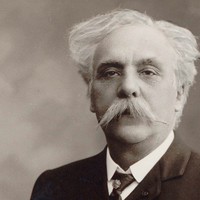

Gabriel Fauré entered a boarding school in Paris at age nine, where his studies emphasized church music and literature. The addition of Camille Saint-Saëns to the school’s faculty introduced Fauré to contemporary music, and upon his graduation in 1865 the young composer won a top prize for his Cantique de Jean Racine, still a favorite among choirs. He spent the next thirty years working as a church organist and composing on the side, issuing mostly small-scale works and a few significant pieces, including his Requiem from 1877. He joined the faculty of the Paris Conservatoire in 1896 and served as the school’s Director from 1905 to 1920. He kept composing after his retirement and only slowed down as his health declined in 1922.

Fauré created the musical comedy Masques et bergamasques in 1919 for Prince Albert I of Monaco. The work combined several existing songs and choruses with instrumental movements drawn from a symphony that Fauré had abandoned fifty years earlier. The suite Fauré assembled from the instrumental movements turned out to be his final orchestral work.

Masques et bergamasques took its inspiration from the Commedia dell’arte tradition, the Italian and French masked comedies that brought us Harlequin, Pierrot, and other stock characters still remembered today. The title itself is a quotation from “Clair de lune” (“Moonlight”), an 1869 poem by the Symbolist poet Paul Verlaine. The word play evokes the actors’ masks and also a dance, the bergamask from Bergamo, Italy, a northern town with a reputation for clowning. The poem’s first stanza (as translated here by Peter Low) suggests a darker sentiment behind those masks:

Your soul is a chosen landscape <br> Charmed by masquers and revelers <br> Playing the lute and dancing and almost <br> Sad beneath their fanciful disguises! <br>

Fauré’s score echoes the mix of history, humor, and wistfulness in Verlaine’s text. The Ouverture is spry and dainty, launching directly into a chipper theme and touching upon more reserved emotions in its contrasting material. The simple Menuet has the easy three-beat lilt typical of that Baroque dance, while the Gavotte stomps with a sturdy pulse, also very much in character with the form’s dancing origins. The Pastorale, which followed the overture in the work’s original form, serves as the finale to the concert suite, replacing the pavane (Fauré’s Opus 50) that closed the stage version. The Pastorale was the only music composed new especially for Masques et bergamasques, and it mirrors the comingled sweetness and pain that Verlaine captured in his poem—a statement especially potent in the immediate aftermath of World War I, as rendered by an old man looking back on a changed world.

Aaron Grad ©2012

Violinist Henryk Wieniawski left his native Poland at the age of eight to study at the Paris Conservatoire. By thirteen, he was touring as an international virtuoso, accompanied in recitals by his younger brother Józef. Wieniawski set aside his itinerant life from 1860 to 1872, when he settled in St. Petersburg at the urging of Anton Rubinstein. The Polish expatriate served as solo violinist to the tsar, led the orchestra and quartet of the Russian Musical Society, and taught at the conservatory that Rubinstein founded, his efforts shaping the so-called Russian school of violin technique.

Composing was a much smaller part of Wieniawski’s life than his performing and teaching, but he did produce a limited body of memorable works. He composed his greatest music during his Russian years, including the Études-caprices, the Second Violin Concerto, and the Fantaisie brillante, a showpiece for violin based on themes from the opera Faust by Charles Gounod. (Faust had enjoyed only modest success when it debuted in Paris in 1859, but an 1862 revival was a smash hit, leading to productions in far-flung cities that included St. Petersburg in 1864 and Moscow in 1866.)

Composers had been adapting each other’s popular tunes for generations, but it was Franz Liszt who elevated the opera fantasy to an art form and a distinctly Romantic one at that; his blend of sentimentality and virtuosity established the template for works such as the Fantaisie brillante. Wieniawski created two versions of his Faust fantasy in 1865, one with piano accompaniment and another with orchestra.

The Fantaisie brillante consists of a single movement divided into five linked sections. The exploratory first section, punctuated with dramatic cadenzas, takes material from the aria “Rien! En vain j’interroge,” in which Faust voices his frustration. The second section moves to more gentle music, derived from Valentin’s “O sainte médaille.” Here the violin uses its throaty lower range to approximate the baritone’s character. The third section returns to the opening key of A minor for agitated music drawn from “Le veau d’or,” in which the fiendish Méphistophélès sings of a golden calf. The fourth section again provides a docile contrast, this time importing love music associated with Faust and Marguerite. The final section, based on a waltz from the opera’s second act, unleashes playful violin antics with quick slurs, bouncing spiccato bows, and glassy harmonics.

Aaron Grad ©2012

Listen to Audio

Listen to Audio

Franz Joseph Haydn became a court composer for Austria’s wealthy Esterhazy family in 1761, and four years later he was put in charge of all the court’s vast musical activities. His patron, Prince Nikolaus Esterhazy, was an avid musician and a true supporter of the arts, but he kept his Kapellmeister on a tight leash, especially during the long stretches of time spent at an isolated summer palace where the musicians had to produce an endless stream of operas and other entertainment. Under those demands, Haydn later wrote, “I was forced to become original.”

In 1779, Haydn negotiated a new contract that gave him more leeway to compose and publish independently, and soon his music was attracting followers throughout Europe. One foreign admirer was a young French count, Claude-François-Marie Rigolet, who commissioned six symphonies that Haydn composed in 1785 and 1786. These “Paris” Symphonies earned Haydn the handsome sum of 25 louis d’or each, plus additional fees for publication. (By comparison, Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart earned only 5 louis d’or for his “Paris” Symphony from 1778.) The Symphony No. 82, though published as the first in the sequence of the “Paris” Symphonies, was actually the last Haydn composed.

Haydn’s “Paris” symphonies capitalized on the large orchestra employed for the Concerts de la Loge Olympique, an ensemble that far outnumbered the private Esterhazy ensemble. It must have had quite an impact when the orchestra struck up the first performance of the Symphony No. 82 in 1787, conducted by its famous mixed-race maestro, Joseph Bologne, Chevalier de Saint-Georges. In the symphony’s first measures, the entire orchestra enters at a fortissimo dynamic, climbing up an arpeggio that defines the home key of C major. The timpani drums add potent force to the opening, repeating a rousing rat-a-tat-tat-tat rhythm. The secondary material, by contrast, enters with all bass instruments silenced except for a lone bassoon, creating an unusually airy texture and foreshadowing the droning bass of the symphony’s finale.

The second movement, an Allegretto, is quite quick and mischievous for a symphonic slow movement. Again there are gaps and delays in the bass line, as well as dramatic exchanges between loud and soft phrases. In the minuet, an oboe caps each stout phrase with a dainty solo, and isolated woodwinds have prominent roles in the contrasting trio section.

This symphony owes its nickname, “The Bear,” to the Vivace finale. The name was not Haydn’s choosing; it was added posthumously, as a reference to the rustic droning figure that appears throughout the movement. Apparently, this sound reminded audiences of the street music played on bagpipes and other folk instruments to accompany the dancing of tamed bears.

Aaron Grad ©2022

This concert and the club2030 happy hour have been canceled. Find more information on our concert cancellation page.

Get driving directions and find nearby parking.

Find dining options close to the venue.

View seating charts to find out where you'll be seating.

SPCO concerts are made possible by audience contributions.

For exclusive discounts, behind-the-scenes info, and more:

Sign up for our email club!