Handel's Messiah

Watch Video

Watch Video

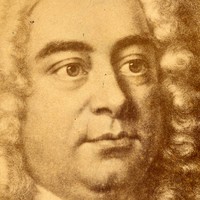

Had George Frideric Handel followed the same career path as his fellow Germans Georg Philipp Telemann and Johann Sebastian Bach, he could have reached the same lofty heights in the realm of Lutheran church music. Instead, Handel embraced opera, a pursuit that led him to Italy and ultimately England. As the coproducer of his own operas, Handel’s fortunes rose and fell with the tastes of London’s ticket-buying public, and so he continually updated his style to stay ahead of changing fashions, proving time and again his staying power as a composer and entrepreneur.

Facing a shrinking audience for the art form that brought him to England, Handel wrote his last Italian opera in 1740 and dedicated himself from that point forward to oratorios in English. An oratorio differs from an opera in that the performance takes place on a concert stage, without sets, staging or costumes. It was church doctrine that drove the distinction: many oratorio subjects were drawn from the Bible, and it was considered blasphemous to dramatize them. Handel took on the most sensitive subject of all in 1741, when he accepted a new libretto offered by Charles Jennens, a Shakespeare scholar and long-time subscriber to Handel’s published works. Extracting verses from the King James Bible and the Book of Common Prayer, Jennens assembled a patchwork text encompassing prophecies of the Messiah and the story of Christ’s death and resurrection.

Handel began composing Messiah on August 22, 1741, and he completed it just 23 days later. Well aware that his dramatization of Christ might be provocative, Handel scheduled the premiere away from London, mounting it instead as a benefit concert in Dublin. For the London debut the following spring, Handel skirted controversy by billing the music simply as a “Sacred Oratorio.” Audiences ended up embracing Messiah, and by 1750 it was an annual staple in London.

Handel’s death in 1759 did not halt the progress of Messiah. Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart was among the eighteenth-century composers who re-orchestrated it for larger forces, and in the nineteenth century, the mania for Handel’s music prompted such spectacles as a centenary performance at London’s Crystal Palace featuring a chorus of more than 2,700 singers and an orchestra of nearly 500 musicians. In recent decades, the revival of historically informed performance practice has brought Messiah closer to its original dimensions, showing off Handel’s masterful score in all its clarity and brilliance.

PART THE FIRST

Messiah opens with an Overture in the French style, progressing from a solemn introduction to a faster fugue. In the first scene, a tenor soloist brings forth prophecies concerning the Messiah from the Book of Isaiah, culminating in the chorus’ proclamation that “the glory of the Lord shall be revealed.”

The second scene begins with a heated statement from a bass soloist that the lord “will shake the heavens and the earth.” The next air (the English equivalent of the Italian aria) intensifies for the line, “For He is like a refiner’s fire,” and the chorus follows with a fugue that churns on the phrase, “And He shall purify.” The third scene turns to the prophecy of the virgin birth, concluding with a sparkling choral fugue, “For unto us a Child is born.”

The fourth scene takes an episode from the Gospel of Luke, in which “shepherds abiding in the field” (portrayed in a brief instrumental movement) receive a visit from an angel bearing “good tidings of great joy.” She is joined by “a multitude of the heavenly host,” represented by the chorus as they sing, “Glory to God in the highest, and peace on earth, good will towards men.”

The final scene of Part I features the soprano in the lively and virtuosic air, “Rejoice greatly.” The soprano and alto come together for a pastoral duet, “He shall feed His flock like a shepherd,” and then the chorus ends the first portion of the oratorio with the cheerful message, “His yoke is easy, and His burden is light.”

PART THE SECOND

The second part of Messiah shifts the mood with a somber minor key and the chorus’ directive to “Behold the Lamb of God.” The ensuing scene ruminates on Christ’s suffering, in music that ranges from the tender alto air, “He was despised” (which only becomes agitated at the point when “He gave His back to the smiters, and His cheeks to them that plucked off His hair”), to the wonderfully oblivious chorus, “All we like sheep have gone astray.” The tenor soloist restores the gravity in the second scene, aided by the chorus in an anguished fugue that proclaims, “He trusted in God, that He would deliver Him.”

Part II goes on to describe the Messiah’s death and ascension. The countertenor’s minor-key air “Thou art gone up on high” is a highlight, as is the music delivered by the bass in one of the most lively numbers of the work, “Why do the nations so furiously rage together?” A stark and brittle tenor air, “Thou shalt break them with a rod of iron,” gives way to the resplendent finale of Part II, the immortal “Hallelujah” chorus.

PART THE THIRD

The final section of Messiah tells of the resurrection, beginning with a humble soprano air, “I know that my Redeemer liveth.” The following chorus, “Since by man came death,” uses dramatic alternations between a cappella choral singing and passages with brisk orchestral accompaniment to highlight the contrast between death and life.

The second scene comprises a recitative and air for bass, in which Handel exploited the sonic possibilities in the phrase, “The trumpet shall sound.” The chorus continues with “Worthy is the Lamb that was slain,” beginning with a glorious chorale supported by the bright sound of trumpets. After this rich finale, the sweet and humble “Amen” builds patiently to its full glory.

Aaron Grad ©2018

Co-presented by the Basilica of Saint Mary and The Saint Paul Chamber Orchestra <br><br> Leadership support for these performances was provided by Gayle and Timothy Ober. <br><br>

Please note: All three performances of Handel's Messiah are currently sold out, but you may sign up for a waiting list for these concerts. We will contact those on the waiting lists if additional tickets become available.

Click here to be added to the December 19, 7:30pm performance wait list.<br> Click here to be added to the December 20, 8:00pm performance wait list.<br> Click here to be added to the December 21, 1:00pm performance wait list.

Get driving directions and find nearby parking.

Find dining options close to the venue.

View seating charts to find out where you'll be seating.

SPCO concerts are made possible by audience contributions.

For exclusive discounts, behind-the-scenes info, and more:

Sign up for our email club!