Mozart's Linz Symphony & Haydn’s Symphony No. 102

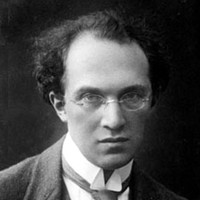

Franz Schreker, the son of a Jewish photographer, was one of the leading opera composers in the German-speaking world during his lifetime. He was ousted from his powerful teaching post in Berlin amid the Nazi rise to power, and after his death in 1934 his scores were suppressed and forgotten. Schreker’s operas never recovered, but several of his instrumental works have regained their rightful place in the international repertoire.

An early highlight for Schreker was the Intermezzo for strings, which he wrote the year he graduated from the Vienna Conservatory. The score was selected as the winner of a composition competition, leading to its publication and a well-reviewed performance in Vienna. Schreker, a violinist himself, possessed a keen ear for string sonorities, and he wrote for a divided string orchestra (with four parts for violin, two each for violas and cellos, and one bass part) that maximized the richness and saturation of the ensemble.

Aaron Grad ©2018

A year after Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart married Constanze Weber without his father’s blessing, the young couple left for Salzburg in the hope of smoothing the family tension. On their return trip to Vienna several months later, they stopped in Linz, where their host, Count Johann Joseph Anton von Thun-Hohenstein, arranged for the court orchestra to perform a concert. Mozart wrote to his father, “I really cannot tell you what kindnesses the family are showering on us. On Tuesday, November 4, I am giving a concert in the theater here and, as I have not a single symphony with me, I am writing a new one at breakneck speed, which must be finished by that time.” It was breakneck speed indeed, for Mozart only arrived on October 30, leaving him less than five days to compose the new piece, copy out the parts, and rehearse with the orchestra.

Mozart’s Symphony No. 36 in C Major, nicknamed “Linz” for its city of origin, betrays no evidence of strained composition. In fact, it is rare among Mozart’s symphonies in that it begins with a leisurely introduction. The opening harmonies wander away from C-major and settle in C-minor, creating a moody counterpoint to the generally bright disposition of the symphony. Further excursions into minor keys, in the first movement’s secondary theme and later in the graceful Andante, echo the tonal rub of the introduction. After a playful Menuetto, the Presto finale sprints through a fluid range of themes, with short motives bouncing among sections. There is a family resemblance between this finale and another C-major movement that is among Mozart’s most famous, the contrapuntal closing of the Symphony No. 41 (“Jupiter”).

Aaron Grad ©2022

After the successes of the 1791 and 1792 concert seasons presented with Johann Peter Salomon, Haydn would have been happy to stay in London. Instead, Prince Anton Esterházy recalled Haydn to Austria, where he spent the next eighteen months. During that time, Haydn gave some lessons to a young firebrand recently arrived in Vienna, one Ludwig van Beethoven.

Haydn arranged a second London visit as soon as he could, and he began composing more symphonies in advance of the trip, which began in February 1794. He stayed through the 1795 spring season, but by then Salomon had disbanded his concert series, so Haydn shifted his presentations to the “Opera Concerts” mounted by the violinist Giovanni Battista Viotti, whose even larger orchestra numbered around sixty players.

Most of the second batch of “London” symphonies added clarinets to the orchestration, and several featured notable effects that inspired nicknames for the works, as in the percussion arsenal of the “Military” Symphony (No. 100), the tick-tock accompaniment of “The Clock” (No. 101) and the iconic timpani lead-in that begins the “Drum Roll” (No. 103). The Symphony No. 102 does not have a descriptive nickname, although it deserves to be known as “The Miracle,” the title ascribed instead to the Symphony No. 96. It was at the premiere of the Symphony No. 102 on February 2, 1795 (and not that of the earlier symphony) that a chandelier crashed to the floor; miraculously, no one was hurt.

The Symphony No. 102 begins with a simple yet striking effect: The home pitch of B-flat, spread among the whole orchestra in several octaves, swells from a piano dynamic and then recedes. (In a nod to his old teacher, Beethoven began his Fourth Symphony with a markedly similar gesture.) The lively body of the movement maintains a thematic link to that initial motive, using held tutti octaves to make surprising pivots to new sections.

The Adagio is an example of Haydn’s self-borrowing; this music appears, in a different key, as the slow movement of a Piano Trio in F-sharp Minor, composed around the same time. The long-lined melodies, beginning in the violins, have a vocal quality about them, and the movement takes on an operatic character as it passes through dramatic minor-key episodes. The Menuet jokes around with three-note tapping figures displaced to cut against the grain of the three-beat meter, while the contrasting trio section is smooth and lyrical, entrusting melodic duties to the mellifluous pairing of oboe and bassoon.

Musicologists have identified the theme of the finale as a Croatian folk tune, specifically, according to Sir William H. Hadow, “the march which is commonly played in Turopol at rustic weddings.” Haydn was born in an area of Austria with large immigrant populations from Croatia and Hungary, and he may have been partly Croatian himself. Later, the long stretches he spent at the remote Eszterháza estate near the Austrian-Hungarian border would have provided more exposure to Slavic traditions.

Aaron Grad ©2012

Get driving directions and find nearby parking.

Find dining options close to the venue.

View seating charts to find out where you'll be seating.

Get driving directions and find nearby parking.

Find dining options close to the venue.

View seating charts to find out where you'll be seating.