Holiday Concerts: Handel’s Messiah

Sponsored By

- December 16, 2017

Sponsored By

Watch Video

Watch Video

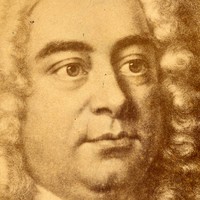

George Frideric Handel fell in love with opera as a teenager in his native Germany, and from the time of his first job playing violin in the opera orchestra in Hamburg, he dreamed of composing his own. He moved for a time to Italy, the birthplace and epicenter of opera, and he managed to parlay his connections with the heir to the throne of England — the German prince who would soon become King George I — to write the first Italian opera composed expressly for London. Handel ruled London’s opera scene for decades as both a composer and impresario, but gradually tastes changed, and he ran headlong into an intractable problem: English audiences had soured on an art form they couldn’t understand.

Ever a shrewd businessman, Handel adjusted by testing different ways of presenting dramatic works sung in English. In the process he invented a new form of oratorio, which combined solo voices, choir and orchestra to dramatize a subject or story on a concert stage, without sets or costumes. He debuted two new English oratorios during his 1738-39 season, including his first written in collaboration with librettist Charles Jennens, a Shakespeare scholar and long-time subscriber to Handel’s published works.

It was Jennens who devised the concept and libretto for the oratorio that would become Handel’s crowning jewel. With texts drawn from the King James Bible and the Book of Common Prayer, and following a patchwork structure that weaves Old Testament prophecy around episodes from the life, death and resurrection of Jesus Christ, Messiah was a curious spin on an oratorio, and a controversial one at that, for daring to approach Christ as a theatrical subject in a commercial enterprise (as opposed to the sacred Passions that covered similar territory, but which were meant for use in church services).

After taking only 23 days to compose the 53 movements of Messiah, Handel opted for a less risky debut in April 1742 by producing it not on his London series but as a benefit concert in Dublin, under the title A Sacred Oratorio. It was only a modest success when it came to London later that season, but Handel continued to rotate it through his oratorio repertoire, refining the score and tailoring solos to whichever star singers he’d booked for that particular season. He started an annual tradition in 1750 of presenting Messiah as a fundraiser for a London orphanage, and that charitable context helped it overcome any lingering whiff of blasphemy.

Messiah has only grown and grown since then. It has been sung by thousands of voices at a time, including amateurs at the sing-along renditions that become popular around the world; more recently, the trend of historically informed performance has led ensembles back toward the nimble, dynamic interpretations that can be achieved with fewer singers and string players — a sound that comes closer to what Handel himself envisioned. Performances have shifted from the traditional performance window during the Lenten season before Easter to become a Christmas staple, and just about any person you ask will recognize the first phrase of the “Hallelujah” chorus, even if they have no idea where it comes from. Messiah has officially transcended music to become a shared cultural treasure.

PART THE FIRST

After a solemn overture in the French tradition, the first part of Messiah brings forth prophecies, especially from the Old Testament Book of Isaiah. The largest chunks of text are delivered by soloists, starting with the tenor who begins with the consoling quotation from the voice of God who says, “Comfort ye, my people,” and who promises in a lively aria that “Ev’ry valley shall be exalted” — meaning that the way will being smoothed for He who will come. Establishing a role that holds throughout Messiah, the chorus responds with collective affirmation, chiming in to attest that “the glory of the lord shall be revealed.”

After the bass announces that “He shall come,” a more solemn aria (Handel wrote alternate versions for alto and soprano) asks, “But who may abide the day of his coming?” Using the same da capo structure found in Italian opera, most of the arias have a contrasting middle section; this one channels the purifying blaze of “refiner’s fire.” The chorus confirms: “And He shall purify the sons of Levi.”

The foretold arrival draws nearer with “good tidings to Zion,” and the bass soloist brings the people from darkness to light in an aria with the unusual feature of having the voice track along with the unadorned bass line. Finally, the chorus erupts with joy, “For unto us a child is born.”

The next sequence visits the pastoral scene of Christ’s birth, with the chorus playing the role of angels who decree, “Glory to God in the highest, and peace on earth, good will towards men.” The soprano aria that bids the people of Zion to “rejoice greatly” is another of the truly operatic moments in Messiah, channeling the religious exuberance in virtuosic runs. The chorus brings Part I to a cheerful conclusion, haling that “His yoke is easy, and His burden is light.”

PART THE SECOND

The middle section of Messiah starts with a turn toward Christ’s suffering, the violence against him made palpable in the throbbing middle section of the alto aria “He was despised.” That stabbing orchestral texture reappears under the exhortations of the chorus that “Surely he hath borne our griefs.” The choral fugue built on the words “And with his stripes we are healed” is a masterpiece of anguished entanglement.

The chorus re-enters as blissfully ignorant as sheep, and next they “laugh Him to scorn” and break Christ’s heart with their rebuke. This dark turn is redeemed with the lifting of gates and doors so the “King of Glory” can enter, and the chorus celebrates with the Lord’s word, “Great was the company of the preachers.” Set in a swaying dance rhythm, a solo aria consoles with the message, “How beautiful are the feet of them that preach the gospel of peace.” The chorus sends that hopeful message out “unto the ends of the world.”

Rage and defiance return in the closing sequence, first in the bass soloist’s memorable pondering of why “the nations so furiously rage together, and continuing in the tenor’s stern warning that “Thou shalt break them with a rod of iron.” This is the leadup to the most iconic section of Messiah, the “Hallelujah” chorus that celebrates the Lord’s omnipotent reign.

PART THE THIRD

The final portion of Messiah explores themes of death and resurrection, starting with the humble soprano aria that testifies, “I know that my redeemer liveth,” with words taken from the harrowing Book of Job. The chorus, singing in starkly contrasted moods, attests to resurrection as the flipside of death, and the bass soloist heralds the trumpet that will announce the raising of the dead. Bringing back the metaphor of Christ as the “lamb of God” from Part II, the final choral sequence provides an apotheosis for the entire arc of Messiah: “Worthy is the Lamb that was slain, and hath redeemed us to God by His blood, to receive power, and riches, and wisdom, and strength, and honour, and glory, and blessing.” All that is left to say is “Amen,” which grows from penitent rumblings to a profusion of choral and orchestral brilliance.

Aaron Grad ©2024

Copresented with The Basilica of Saint Mary

Get driving directions and find nearby parking.

Find dining options close to the venue.

View seating charts to find out where you'll be seating.

Get driving directions and find nearby parking.

Find dining options close to the venue.

View seating charts to find out where you'll be seating.