Jonathan Biss Plays Beethoven’s Second Piano Concerto

Sponsored By

- February 2, 2018

Sponsored By

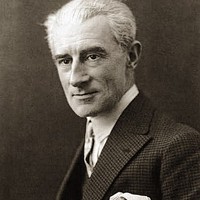

At the start of World War I, the 39-year-old Maurice Ravel volunteered as a truck and ambulance driver, forcing him to set aside Le tombeau de Couperin, a work-in-progress for solo piano honoring the French Baroque composer François Couperin. By the time Ravel finished the suite in 1917, it had acquired a more personal meaning, with each of the six movements dedicated to friends killed in the war.

Ravel transcribed four of the movements for chamber orchestra in 1919. Starting with the fluid melody of the Prélude, the oboe has an outsized role in the orchestration, echoing its prominence as a solo instrument in the Baroque era. Ravel dedicated this movement to Lieutenant Jacques Charlot (the godson of his music publisher), who died in battle in 1915.

The second movement, a Forlane, is based on a lively and flirtatious couple’s dance that entered the French court via northern Italy. Ravel sketched this movement before the war and subsequently dedicated it to the Basque painter Gabriel Deluc, who was killed in 1916.

The oboe returns to the fore in the Menuet, a French dance distinguished by its stately, three-beat pulse. Ravel dedicated this section to the memory of Jean Dreyfus, whose stepmother, Fernand Dreyfus, was one of Ravel’s closest confidantes during the war.

The Rigaudon pays tribute to two family friends of Ravel: Pierre and Pascal Gaudin, brothers killed by the same shell on their first day at the front in 1914. When faced with criticism that this unabashedly upbeat movement was too cheerful for a memorial, Ravel purportedly responded, “The dead are sad enough, in their eternal silence.”

Aaron Grad ©2018

(Duration: 28 min)

When the 21-year-old Ludwig van Beethoven arrived in Vienna in 1792, he was following in the footsteps of his hero Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, whose death a year earlier left an opening for a hotshot keyboard player that the young Beethoven eagerly filled. In those early years, before his reputation earned him a measure of artistic independence (and before his deafness cut him off from the world), Beethoven hustled for all sorts of paying gigs around town — teaching lessons, performing public and private concerts and writing accessible music that could be published and sold to amateurs. And just as Mozart wowed Vienna with self-produced concerts centered on a stream of new piano concertos, Beethoven took up the concerto as an ideal vehicle for self-promotion.

The earliest piano concerto that Beethoven completed was this one in B-flat, although it became known as No. 2, since the later C-major concerto was published first. Initial sketches of the B-flat concerto date back as far as 1788, when Beethoven was still a teenage viola player in the court orchestra in his hometown of Bonn, and then he reworked it substantially in 1794 to prepare for his first Mozart-style concert the following spring. Beethoven made additional revisions in 1798, and a decade later he wrote out cadenzas, for the benefit of other performers less gifted than he was in the art of improvisation.

Demonstrating just how well Beethoven had internalized the refined craft of Mozart and Franz Joseph Haydn, this concerto’s opening measures exhibit textbook contrast and balance between the two offsetting phrases. The first is loud, rhythmically robust, scored for the whole orchestra, and in the home key of B-flat; the second is soft, rhythmically smooth, scored just for strings, and in the contrasting key of F. These motives develop through a high-energy movement of brilliant piano figurations, surprising harmonic shifts, and galloping rhythms. With the insertion of the cadenza that Beethoven added in the heart of his “middle period,” stark counterpoint and insistent rhythmic repetitions introduce an extra note of firmness and drama.

The central Adagio, after elaborating a gentle theme, adds its most striking detail at the point when the cadenza would normally appear. Instead of inserting a virtuosic flourish, Beethoven gives the soloist a single melodic line to convey “with great expression,” alternating with comments from the orchestra as the movement draws to a close. The Rondo finale especially benefited from the 1798 revision, which transformed the square rhythm of the original main theme to the punchy, syncopated motive we know today.

Aaron Grad ©2023

Watch Video

Watch Video

After leaving stormy Scotland, which inspired the Hebrides Overture and the Symphony No. 3 (“Scottish”), the 20-year-old Mendelssohn continued his grand tour in Italy, sparking a symphony that, according to the composer, was “the jolliest piece I have ever done.”

Mendelssohn sketched part of that symphony while in Italy in 1830–31, and he completed the work in 1833, using it to fulfill a prestigious commission from the Philharmonic Society of London, the same group that had commissioned Ludwig van Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony. Mendelssohn made substantial revisions to the symphony’s final three movements in 1834, and he intended to revise the first movement, too, but he postponed that task and finally suppressed the symphony altogether. The work was published posthumously as the Symphony No. 4, although it was actually composed third. This performance restores the original conception of the 1833 version, using a critical edition prepared by the conductor Christopher Hogwood.

Mendelssohn’s bright impressions of Italy are borne out by the bouncing themes and running triplet pulse of the Allegro vivace movement that opens the symphony. Still, this is no mere musical “postcard” — just note the finely wrought development section, which shows the work of a composer equally fluent in Johann Sebastian Bach’s formal counterpoint and Beethoven’s obsessive manipulation of recurring themes. The Andante con moto may have been influenced by a religious processional Mendelssohn witnessed in Naples, an image that fits with the movement’s walking bass and grave harmonies.

The moderate pace and smooth flow of third movement resemble the symphonic minuets of Mozart and Haydn, as opposed to the more rambunctious scherzos popularized by Beethoven. In the contrasting trio section, the horns and bassoons indulge in spacious phrases that impart an outdoor quality, until the mood turns momentarily menacing with the interjection of trumpets, timpani, and a stern minor key.

For the symphony’s whirlwind finale, Mendelssohn borrowed lively rhythmic patterns from Italian folk dancing. He named the movement after the saltarello, a dance from central Italy defined by its fast triplet pulse and its leaping movements.

Aaron Grad ©2023

Please be aware that there will be heavier than normal traffic in downtown Saint Paul prior to our evening concert on FRIDAY, FEBRUARY 2 due to an event at the XCEL CENTER and events surrounding the SAINT PAUL WINTER CARNIVAL

Get driving directions and find nearby parking.

Find dining options close to the venue.

View seating charts to find out where you'll be seating.

SPCO concerts are made possible by audience contributions.

For exclusive discounts, behind-the-scenes info, and more:

Sign up for our email club!