Lise de la Salle Plays Ravel

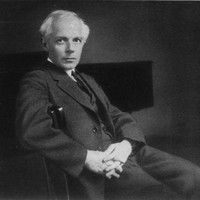

By 1939, Béla Bartók’s life in Hungary was crumbling around him, especially after the Nazis seized his publisher in Vienna, but he felt bound to stay in Europe to care for his gravely ill mother. It was a much-needed relief then when the fabulously wealthy Swiss conductor and patron Paul Sacher commissioned a new piece for his chamber orchestra, an offer that came with the use of a vacation house in Switzerland. Bartók spent fifteen days that summer avoiding newspapers and composing the Divertimento for strings.

The Divertimento’s title and carefree attitude align with Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, who elevated his era’s preferred form of party music to new levels of sophistication. In another historical nod, the scoring honors the Baroque concerto grosso tradition, in which individual voices emerge from the larger string orchestra to create contrasting colors and densities of sound. The themes themselves are quintessential Bartók, steeped in the folksongs of his native Hungary and chiseled into telltale fragments with an uncanny sense of symmetry and order.

Contrasting the rustic cheer of the first movement, the Molto adagio middle movement circulates from smooth, pacing lines into a swirling cloud of trills before dissipating for a quiet conclusion. The Allegro assai finale returns to fun and games in the form of call-and-response melodies, sudden interruptions, and a plethora of string effects, all capped with a manic sprint.

Aaron Grad ©2023

Listen to Audio

Listen to Audio

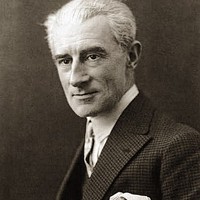

Mozart entered the massive Piano Concerto in C Major into his catalog of finished works on December 4, 1786, and probably performed it the next night in Vienna. Then, on December 6, he marked another piece as completed, his first symphony in three years. Mozart debuted the new D-major symphony on January 19, 1787 in Prague, where he had traveled to see the successful production of his 1786 opera The Marriage of Figaro. He had wanted to visit London that season, and may have even begun the symphony in anticipation of such a trip, but the journey stalled when Mozart’s father Leopold refused to provide childcare. Fortunately, the less ambitious trip to Prague still proved valuable, with Mozart securing the opera commission that would result in Don Giovanni. At a time when Mozart’s star-power in Vienna was waning, he soaked up the adoration he received in Prague, where he is purported to have said, “Meine Prager verstehen mich” (“My Praguers understand me”).

The Prague Symphony has some unusual features in its form. It is one of only three symphonies in which Mozart used a slow introduction, a feature more typical of Haydn. It also omitted the third-movement minuet, a more recent but by then common addition to the symphonic form. Evidence suggests that Mozart composed the finale last, possibly intended as a replacement for the earlier Paris Symphony in the same key and also in three movements, and only subsequently added the first two movements to create an altogether new symphony.

However Mozart developed it, the Symphony No. 38 is a marvel of his mature symphonic craft, standing with his final group of three symphonies from 1788 among the finest specimens of the Viennese Classical style. The slow introduction heightens the gravitas of the work, especially the brooding D-minor passages that foreshadow like-minded music in the forthcoming Don Giovanni score. When the Allegro body of the movement begins, it has some of the breathless energy of the overture to The Marriage of Figaro, delighting in running sixteenth-notes and dynamic contrasts, while still retaining a patient, chorale-like layer underneath. The brilliant exuberance of this music is expected, a hallmark of Mozart’s music since he was a teenager; it is the subtle shading and layering that sets it apart.

The Andante is meatier than many equivalent slow movements, built in a full-figured sonata form rather than something more streamlined. (The finale likewise uses a sonata form, as opposed to the more casual rondo that typically comes last.) The vertiginous chromatics, introduced in the violins’ arcing melodic line at the beginning, ripple throughout the movement in all manner of passing dissonances and pungent collisions. The Presto conclusion quotes music from The Marriage of Figaro, in which Susanna tries to rush Cherubino out the window. It is a fittingly dramatic sendoff for such an emotionally charged symphony, and it must have delighted those Praguers who gobbled up Figaro and all things Mozart.

Aaron Grad ©2011

Get driving directions and find nearby parking.

Find dining options close to the venue.

View seating charts to find out where you'll be seating.

SPCO concerts are made possible by audience contributions.

For exclusive discounts, behind-the-scenes info, and more:

Sign up for our email club!