Mozart and Ravel

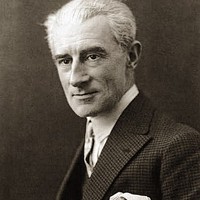

At the start of World War I, the 39-year-old Maurice Ravel volunteered as a truck and ambulance driver, forcing him to set aside Le tombeau de Couperin, a work-in-progress for solo piano honoring the French Baroque composer François Couperin. By the time Ravel finished the suite in 1917, it had acquired a more personal meaning, with each of the six movements dedicated to friends killed in the war.

Ravel transcribed four of the movements for chamber orchestra in 1919. Starting with the fluid melody of the Prélude, the oboe has an outsized role in the orchestration, echoing its prominence as a solo instrument in the Baroque era. Ravel dedicated this movement to Lieutenant Jacques Charlot (the godson of his music publisher), who died in battle in 1915.

The second movement, a Forlane, is based on a lively and flirtatious couple’s dance that entered the French court via northern Italy. Ravel sketched this movement before the war and subsequently dedicated it to the Basque painter Gabriel Deluc, who was killed in 1916.

The oboe returns to the fore in the Menuet, a French dance distinguished by its stately, three-beat pulse. Ravel dedicated this section to the memory of Jean Dreyfus, whose stepmother, Fernand Dreyfus, was one of Ravel’s closest confidantes during the war.

The Rigaudon pays tribute to two family friends of Ravel: Pierre and Pascal Gaudin, brothers killed by the same shell on their first day at the front in 1914. When faced with criticism that this unabashedly upbeat movement was too cheerful for a memorial, Ravel purportedly responded, “The dead are sad enough, in their eternal silence.”

Aaron Grad ©2018

English composer John Casken’s That Subtle Knot, a double concerto for violin, viola, and orchestra, was commissioned by Thomas Zehetmair, Ruth Killius, and The Sage Gateshead. The composer has written the following program note.

The title comes from a poem by John Donne, The Ecstasy, in which two lovers sit. Their hands, entwined, ‘did thread/Our eyes, upon one double string.’ This image seemed perfect for my double concerto. The relationship develops between the solo instruments through the exploration of independent lines, lines shared, lines in opposition, always with a sense of being drawn together with one purpose. The dialogue is in the spirit of chamber music, the orchestra taking up fragments of the solo lines, or sustaining notes, and in the faster passages acting as an equal force, driving the music forward.

John Casken ©

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart wrote his three final symphonies in the span of eight weeks during the cash-strapped summer of 1788, when he was reduced to pleading with friends for loans, moving his growing family to the suburbs, and pursuing dead-end leads for his music. Whatever opportunity prompted the symphonies seems not to have panned out, and he probably didn’t hear all three before he died. He did revisit the G-minor symphony at some later point to add clarinets and make other adjustments, suggesting that he found an audience for that one at least.

The Symphony No. 40 in G Minor was only the second example that Mozart set in a minor key, and it was a world apart from the Symphony No. 25 that he wrote as a seventeen-year-old. This bigger, bolder, proto-Romantic symphony begins with a peculiar and essential quirk of phrasing that assigns the violas to quiver through one measure of bare accompaniment. When the violins enter a moment later with a theme that sighs three times before leaping up, there is a subtle rub between what our ears hear as the strong beat and the underlying architecture of the phrase. The result is a persistent and restless feeling of propulsion, as if each phrase must scrabble forward to stay ahead of the surge.

The Andante second movement is the only portion of the symphony that moves away from the turbulence of G-minor, and even here patterns of hiccupping rhythms and delayed resolutions recall the stormy first movement. The Menuetto is unusually grave for the portion of a symphony that often serves as a light diversion, with respite only coming in the contrasting trio section. The finale, with its heated dialogue of soft and loud phrases, embodies the passion and drama that Mozart honed on the operatic stage, most recently in Don Giovanni.

Aaron Grad ©2025

Get driving directions and find nearby parking.

Find dining options close to the venue.

View seating charts to find out where you'll be seating.

Get driving directions and find nearby parking.

Find dining options close to the venue.

View seating charts to find out where you'll be seating.