Mozart’s Paris Symphony

Sponsored By

- September 28, 2019

Sponsored By

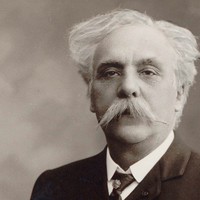

Paris was a magnet for talented young prospects like Fauré, who arrived in 1854 as a nine-year-old, sent by his family to study at a musical boarding school. He only reached the upper echelon of Parisian musical life in his fifties, when he earned a faculty position at the Paris Conservatoire. He went on to serve as the school’s director from 1905 to 1920, and his leadership shaped French music for generations.

Honoring the Commedia dell’arte tradition of masked comedies, Faure created Masques et bergamasques in 1919, combining existing songs and choruses with instrumental movements adapted from an unfinished symphony from fifty years earlier. The Pastorale, placed last in this suite of instrumental music that Faure extracted from the larger stage work, was the only music composed new especially for Masques et bergamasques. It mirrors the comingled sweetness and pain that the French poet Paul Verlaine captured in Clair de lune (“Moonlight”), his immortal poem that included the phrase which became Faure’s title.

Aaron Grad ©2019

Thanks to bootlegged manuscripts that circulated around Europe, Joseph Haydn (1732–1809) was already famous in Paris by the time he negotiated a new contract in 1779 with his longtime employers, Austria’s Esterhazy family, granting him new leeway to compose and publish works for his own profit. One foreign admirer who took advantage was a young French count, Claude-Francois-Marie Rigolet; he promised Haydn the handsome sum of 25 louis d’or each, plus additional fees for publication, for the works that became the six “Paris” symphonies, Nos. 82–87, composed in 1785 and 1786. (By comparison, Mozart earned only 5 louis d’or for his “Paris” symphony from 1778.) The huge sound of Haydn’s Symphony No. 87 in A, tailored to the large orchestra that he knew would be used in Paris, is a world away from the fledgling symphonies created nearly thirty years earlier for the Esterhazy’s tiny private ensemble, but in both contexts the aptly nicknamed “Father of the Symphony” knew how to maximize the collective and individual contributions from an orchestra.

Aaron Grad ©2019

Early in his career, before gaining traction as a composer, Camille Saint-Saëns (1835–1921), was best known as a piano and organ virtuoso, and he developed a knack for writing music that could bring the best out of star performers. One fruitful relationship began in 1859, when the 15-year-old Spanish violinist Pablo de Sarasate asked Saint-Saens for a new work. The composer was impressed enough that he offered up the Violin Concerto No. 1, and he followed four years later with a shorter showpiece, the Introduction and Rondo capriccioso. Saint-Saens added the performance indication of malinconico, or “melancholy,” to the andante tempo marking of the Introduction. The solo violin delivers a mournful melody in a minor key, and the strummed plucks of the accompanying violins suggest the sound of a Spanish guitar.

Aaron Grad ©2019

(Duration: 17 min)

Desperate for a job away from his hometown of Salzburg, the 22-year-old Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart traveled with his mother to spend part of 1778 in Paris, a city that had adored him as a child prodigy. The only job lead he generated was for a post as an organist at Versailles, which he declined, and amid the professional disappointment, he faced personal tragedy when his mother fell ill and died.

One of the few bright spots in that dismal trip was a commission to compose a symphony for the Concert Spirituel, a series that featured one of Paris’ biggest and best-established orchestras. Active for more than fifty years by that point, the orchestra even had its own signature flourish, the premier coup d’archet: a unison bow-stroke at the start of a work that showed off the ensemble’s precision. Mozart used all the forces at his disposal in his “Paris” Symphony, writing for an unusually large orchestra that included clarinets. And he even incorporated the stereotypical coup d’archet at the start of his symphony, but this was perhaps a bit cynical, considering that Mozart wrote to his father, “These oxen here make such a to-do about it! What the devil! I can see no difference — they merely begin together — much as they do elsewhere.”

The symphony’s opening motive rises rapidly up the scale, a gesture that circulates throughout the first movement. In a sly moment of the development section, that scale-figure makes the shocking “mistake” of going a half-step too far. The Andante middle movement plays like a scene from a comedy of manners, with calm and courtly themes that pause politely to let each other speak. Forgoing a minuet and instead using the older three-movement pattern, the symphony proceeds directly to the finale that draws the listeners in with a scurrying piano start and then blasts a forte response. The contrapuntal treatment of the second theme foreshadows the famous fugal conclusion to Mozart’s last symphony, No. 41 (“Jupiter”), composed a decade later.

Aaron Grad ©2023

Get driving directions and find nearby parking.

Find dining options close to the venue.

View seating charts to find out where you'll be seating.

Get driving directions and find nearby parking.

Find dining options close to the venue.

View seating charts to find out where you'll be seating.