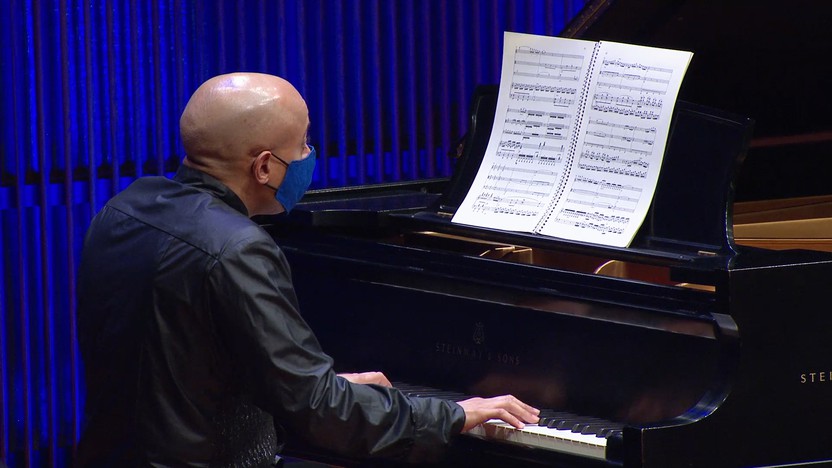

Piano Quartets with Stewart Goodyear

After writing a monumental symphony that dwarfed his two previous efforts (and those of all composers who came before him), Beethoven gave the Symphony No. 3 in E-flat Major the subtitle of “Bonaparte,” honoring Napoleon Bonaparte, the military mastermind of Revolutionary France. But the composer’s adulation turned to disgust in 1804, when he learned that Napoleon had crowned himself Emperor. According to the student who delivered the disturbing news, Ferdinand Ries, “Beethoven went to the table, seized the top of the title-page, tore it in half and threw it on the floor.” When preparing the symphony for publication in 1806, Beethoven re-titled it “Sinfonia eroica, composed to celebrate the memory of a great man.” The unspecified “great man” may have been Prince Louis Ferdinand of Prussia, a patron’s friend who died in 1806 fighting against Napoleon’s army.

While Beethoven lobbied to get the daunting score and parts for his “heroic” symphony published, he also advocated for the release of solo piano and chamber music versions, to appeal to the growing market of amateurs who wanted to recreate symphonies at home in the age before recordings. An anonymous arrangement of the symphony did in fact go to print just months after the orchestral version, scored for violin, viola, cello and piano. The version heard here is a different arrangement for the same quartet instruments, created sometime later by the very same Ferdinand Ries who had been there for the birth of the Eroica Symphony.

After his teenaged apprenticeship with Beethoven, Ries went on to become one of Europe’s most successful pianists. He presumably created this quartet arrangement for his own performances, and it was only published after his death, in 1858. Unlike the typical transcriptions for amateurs, which placed most of the important music in the piano part in case the other players were shaky or absent, Ries’ arrangement demands virtuosity and cohesion from all four players, prefiguring the full-throated chamber music for piano and strings from the likes of Schumann and Brahms.

The symphony’s second movement, labeled a funeral march, sinks into a prolonged state of despair that might induce misery if not for its undeniable grace and beauty. One major challenge in transcribing Beethoven’s symphonies is how to emulate the huge contrasts and dynamic swings in the orchestration; Ries’ strategy here was to hold back the strings at the start, so that their entrance could emulate the contrasting colors of Beethoven’s woodwinds.

— © Aaron Grad

Aaron Grad ©2020

My piece Tableau No. X for solo trumpet is a part of a series of solo pieces that I’ve been writing for the past several months. Each work is for a different solo instrument and explores their expressive possibilities. Some composers of the latter half of the 20th century have explored this idea, notably Luciano Berio (14 Sequenzas), Vincent Persichetti (25 Parables), and Elliott Carter (6 Figments and 5 Retracings). Coincidentally, these are some of my favorite composers. This Tableau was commissioned by The Saint Paul Chamber Orchestra for Lynn Erickson (Trumpet).

Tyson Davis ©2020

My piano quartet was commissioned by the Kingston Chamber Music Festival and was performed by the Clarosa Piano Quartet in the summer of 2016. The compact, one-movement work is divided by four sections, each section performed without break. The first section is relentless in its drive, the strings at first accompanying the piano's dissonant, syncopated theme before exploding in their own energy.

The second section is a calmer dance in ternary form, hypnotic in its 5/8 rhythm. The following slow section is lyrical and somber, the tension building with chromatic harmony, and finally relaxing in the key of D Major. The finale is a toccata, a medley of the themes in the preceding movements. The piece closes with all the instruments quoting the theme of the first section.

— © Stewart Goodyear

Stewart Goodyear ©2020

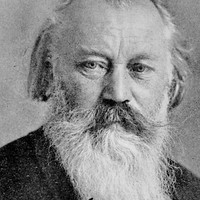

After fellow composer Robert Schumann’s leap into the Rhine River and confinement to an insane asylum in 1854, his young friend Johannes Brahms moved to Düsseldorf to help manage the Schumann household and care for the children while Robert’s wife, renowned pianist Clara Schumann, supported the family playing concert tours. This arrangement ended after Robert’s death two years later, forcing Brahms to reconcile both the loss of his mentor and a painful separation from Clara.

The next years were filled with setbacks and disappointments, especially in the realm of orchestral music. Brahms finally regained his footing by following the path of both Schumanns and composing rigorous chamber music, even though it was hardly the fashion in a musical culture dominated by the outrageous experiments of composers Richard Wagner and Franz Liszt.

After completing a breakthrough string sextet, Brahms crafted three immortal scores in formats championed by Robert Schumann: two piano quartets (both from 1861) and a piano quintet (1862). Besides Schumann, Brahms could look to the example of Mozart, who composed two quartets for the same combination of piano, violin, viola and cello. Like Mozart, Brahms placed his First Piano Quartet in the stormy key of G Minor, defying from the start the idea of chamber music as good-natured music for the amusement of amateurs.

The other titan standing over Brahms’ shoulder was Beethoven, who perfected the art of distilling motives — short musical ideas or figures — down to their essence. The main theme of Brahms’ opening Allegro movement, introduced in quiet octaves by the piano alone, is a model of Beethovenian efficiency. Four evenly spaced quarter-notes set up two signature intervals: The first pair outlines a wide leap up, while the second pair ascends by just a narrow half-step. The very next measure flips the direction, tracing a downward leap and a descending half step. These simple but distinctive ingredients allow for countless manipulations, with each two-note unit measured against the listener’s memory of what has come before.

Whether or not we recognize it consciously, there is a familiarity to the wispy melody that starts the Intermezzo, with its heavy emphasis on the rising half-step at the end of each phrase. The Andante con moto third movement might seem a world apart, with its songlike melody and stately bearing, and yet once again it traces a theme in steady quarter-notes, the first two notes forming an upward leap, the second two notes countering with a rising half-step. Patterns of pulsing triplets echo the similar figures in the Intermezzo.

The triumphant climax of the contrasting Animato section is a hard summit to top, but the finale rises to the challenge with its Rondo alla zingarese. The brisk tempo and vigorous accents mimic the Hungarian or “Gypsy” sound that Brahms fell in love with as teenager, when Hungarian refugees passed through his hometown of Hamburg en route to America. Even here the rigorous logic holds firm, with accented half-steps and other familiar intervals advancing the emphatic message of this epic quartet.

— © Aaron Grad

Aaron Grad ©2020

Get driving directions and find nearby parking.

Find dining options close to the venue.

View seating charts to find out where you'll be seating.

SPCO concerts are made possible by audience contributions.

For exclusive discounts, behind-the-scenes info, and more:

Sign up for our email club!