Ravel’s Mother Goose

Sponsored By

- April 10, 2015

- April 11, 2015

Sponsored By

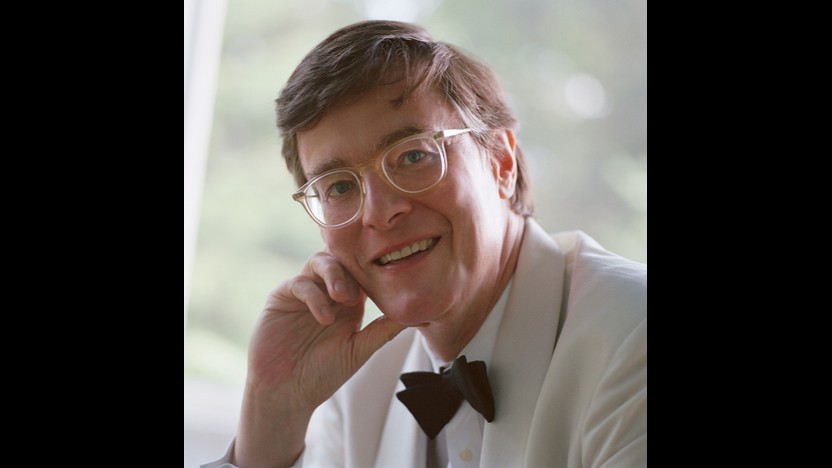

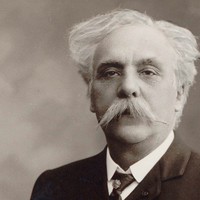

Gabriel Fauré entered a boarding school in Paris at age nine, where his studies emphasized church music and literature. The addition of Camille Saint-Saëns to the school’s faculty introduced Fauré to contemporary music, and upon his graduation in 1865 the young composer won a top prize for his Cantique de Jean Racine, still a favorite among choirs. He spent the next thirty years working as a church organist and composing on the side, issuing mostly small-scale works and a few significant pieces, including his Requiem from 1877. He joined the faculty of the Paris Conservatoire in 1896 and served as the school’s Director from 1905 to 1920. He kept composing after his retirement and only slowed down as his health declined in 1922.

Fauré created the musical comedy Masques et bergamasques in 1919 for Prince Albert I of Monaco. The work combined several existing songs and choruses with instrumental movements drawn from a symphony that Fauré had abandoned fifty years earlier. The suite Fauré assembled from the instrumental movements turned out to be his final orchestral work.

Masques et bergamasques took its inspiration from the Commedia dell’arte tradition, the Italian and French masked comedies that brought us Harlequin, Pierrot, and other stock characters still remembered today. The title itself is a quotation from “Clair de lune” (“Moonlight”), an 1869 poem by the Symbolist poet Paul Verlaine. The word play evokes the actors’ masks and also a dance, the bergamask from Bergamo, Italy, a northern town with a reputation for clowning. The poem’s first stanza (as translated here by Peter Low) suggests a darker sentiment behind those masks:

Your soul is a chosen landscape <br> Charmed by masquers and revelers <br> Playing the lute and dancing and almost <br> Sad beneath their fanciful disguises! <br>

Fauré’s score echoes the mix of history, humor, and wistfulness in Verlaine’s text. The Ouverture is spry and dainty, launching directly into a chipper theme and touching upon more reserved emotions in its contrasting material. The simple Menuet has the easy three-beat lilt typical of that Baroque dance, while the Gavotte stomps with a sturdy pulse, also very much in character with the form’s dancing origins. The Pastorale, which followed the overture in the work’s original form, serves as the finale to the concert suite, replacing the pavane (Fauré’s Opus 50) that closed the stage version. The Pastorale was the only music composed new especially for Masques et bergamasques, and it mirrors the comingled sweetness and pain that Verlaine captured in his poem—a statement especially potent in the immediate aftermath of World War I, as rendered by an old man looking back on a changed world.

Aaron Grad ©2012

With Sonic Eclipse Matthias Pintscher has composed a three-part cycle for ensemble. The first two parts, Celestial Object I and II, were premiered by the Scharoun Ensemble in Berlin and Zermatt at the Berliner Philharmoniker’s summer academy, and the third, Occultation, was premiered by Klangforum Wien in 2010.

For Pintscher, the phenomenon of the eclipse—the passing of one celestial body over another and the resultant blackout at the moment of total eclipse—is a symbol of a compositional process of convergence and finally the momentary fusion of completely diverse elements. He explains, “The musical idea is that in the first piece [Celestial Object I], the trumpet, and in the second, the horn, take over a solo function. The contours of the two pieces are quasi laid one over another in the third part, though the material of both the pieces is entirely heterogeneous and at the moment of coming together, fuses together. I was interested in investigating the repertoire for two very different instruments which belong to one family, and in allowing both instruments to sound very differently. This entirely heterogeneous repertoire of sounds and shapes is slowly brought together and layered, and finally the ensemble is also drawn in, so that everything merges into one voice, one instrument and sound gesture, then subsequently also falls apart. Figuratively, this corresponds exactly to an eclipse.”

Pintscher attributes his interest in the cyclical, that is, in compositions in several parts with related subjects, to a need to continually keep moving forward: “I would like to carry on composing works that I have just completed. It is about searching for a completely new task and yet moving organically from one state to the next.”

In Celestial Object I and II, the solo horn and trumpet parts are treated differently: The trumpet is “lighter, more flowing, more giocoso con brio, with florescences, festoons.” (The horn, in Celestial Object II, by contrast, plays in long, melodious lines…) The trumpet plays Celestial Object I experimentally, with virtuosity.

Marie Luise Maintz ©

The composer has provided the following program note:

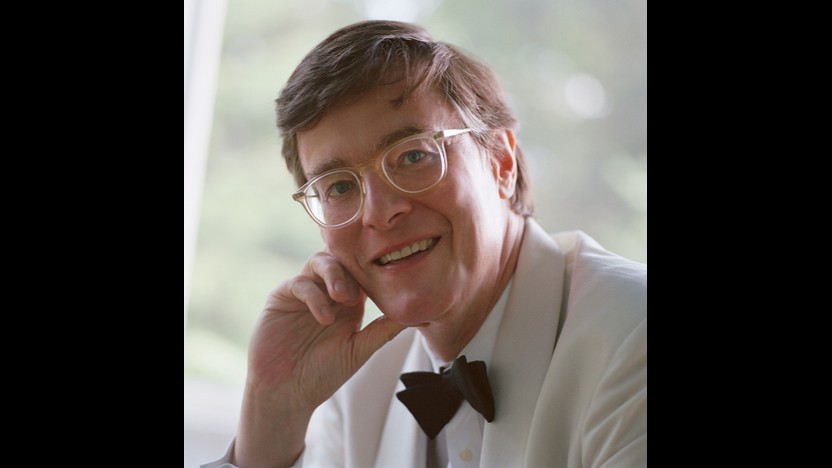

I finished composing Megalith in 2014, in response to a joint commission from The Saint Paul Chamber Orchestra, Tanglewood Music Center of the Boston Symphony, and Works and Process at the Guggenheim Museum in New York. It’s a single-movement work that lasts a little more than twenty minutes, and treats the various blocks of instruments that make it up largely as separate entities. This creates a kind of meta-counterpoint in which the solo piano initiates and responds to activity in the surrounding instruments, rather than merely floating atop an accompanying ensemble. For this reason, some instruments are physically separated from others.

The basic materials come from a conflation of certain Gregorian melodic fragments with elements of a well-known raga.

Over many years I have had the great good fortune to compose several works for the incomparable Peter Serkin. His magisterial virtuosity and extraordinary expressiveness make his playing a wonderful vehicle for a composer to express his thoughts. I’m honored that he is the soloist in these performances.

Charles Wuorinen ©2014

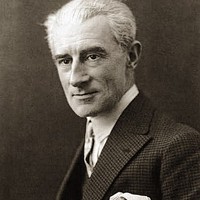

Ravel was a regular guest at the Sunday evening salons hosted by Cipa and Ida Godebski, a Polish couple living in Paris, and on several occasions he vacationed with the family at their country house. Over the course of visits between 1908 and 1910, Ravel composed a set of pieces for piano (scored for four hands) dedicated to the young Godebski children, Mimie and Jean. He called the suite Ma mère l’oye (Mother Goose), and he fashioned the “five children’s pieces,” as he subtitled them, out of popular fairy tales. The title and two of the tales came from Charles Perrault, a seventeenth-century French writer and the father of the fairy tale as a literary genre. His 1697 opus, Tales and Stories of the Past with Morals: Tales of Mother Goose, immortalized Sleeping Beauty, Tom Thumb, and many other classic characters. Other tales came from Madame d’Aulnoy, a rival of Perrault. One more timeless story, Beauty and the Beast, first appeared in an eighteenth-century collection.

The orchestral version of Mother Goose owes its existence, indirectly, to Serge Diaghilev and Igor Stravinsky. After the sensational appearances in Paris by the Ballets Russes, the French impresario Jacques Rouché countered by renting out the Théâtre des Arts and assembling productions with leading French composers and artists. Rouché asked Ravel for a new ballet, and the composer obliged by orchestrating Mother Goose, adding a prelude and scene and providing connecting interludes.

Following the dreamy prelude, the Spinning-wheel Dance and Scene establishes a frame story for the ballet, in which Sleeping Beauty trips over an old woman’s spinning wheel, pricks her finger, and falls into a magical slumber. The Pavane of Sleeping Beauty is a short and mournful dance; like Ravel’s famous Pavane pour une infante défunte, orchestrated a year earlier, this Pavane retains the ceremonial quality of the Italian court dance it is named for.

The next scene visits The Conversation of Beauty and the Beast, in which the clarinet leads a beauteous waltz and the contrabassoon makes beastly interjections. In Tom Thumb, the little protagonist drops breadcrumbs to guide his way home and becomes flummoxed as the chirping birds steal his crumbs. Laideronnette, Empress of the Pagodas uses pentatonic themes and tam-tam strikes to evoke an Asian setting. The final scene, The Fairy Garden, blooms from delicate solos into a resplendent finale for full orchestral forces, celebrating the rising sun and Sleeping Beauty’s awakening.

Aaron Grad ©2012

Peter Serkin is represented by Kirshbaum Demler & Associates, Inc. Mr. Serkin is a Steinway Artist and has recorded for Arcana, Boston Records, Bridge, Decca, ECM, Koch Classics, New World Records, RCA/BMG, Telarc and Vanguard Classics.

Get driving directions and find nearby parking.

Find dining options close to the venue.

View seating charts to find out where you'll be seating.

SPCO concerts are made possible by audience contributions.

For exclusive discounts, behind-the-scenes info, and more:

Sign up for our email club!