SPCO’S WEST SIDE SERIES Barber’s Adagio for Strings Hidden

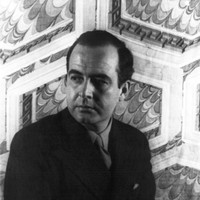

Samuel Barber enrolled in the founding class at Philadelphia’s Curtis Institute of Music at the age of 14. He went on to win the American Academy’s prestigious Rome Prize, which bankrolled his Italian residency from 1935 to 1937. During that time, Barber composed his String Quartet (Opus 11) as well as an adaptation for string orchestra of the quartet’s slow movement, a haunting Adagio that was destined to become one of the most recognizable compositions of the century.

The string orchestra version of the Adagio made its public debut in 1938 during a radio broadcast by Arturo Toscanini and the NBC Symphony Orchestra. The work became an instant favorite with the public, and its success launched Barber’s international career.

The first significant use of the Adagio as music for mourning came in 1945, when radio stations broadcast the work following the announcement of Franklin D. Roosevelt’s death. The tradition continued with performances at the funerals of John F. Kennedy, Grace Kelly and Leonard Bernstein, among many others. The score has also appeared in many films, from its wrenching role in Platoon to a sardonic cameo in Amélie.

The musical language of Barber’s Adagio is deceptively simple. Melodically, lines move in long strands of rising steps, evoking a sense of reaching and yearning. Harmonically, the energy builds through drawn-out suspensions, creating momentary surges of tension and release over a glacially slow sequence of bass notes. It is a simple and elegant design, one that evokes as much emotion, note-for-note, as any piece of music in recorded history.

Aaron Grad ©2022

Commissioned for the SPCO by community supporters Bill and Susan Sands in collaboration with the American Composers Forum.

Born into a musical family in the historically Black neighborhood of Rondo in Saint Paul, PaviElle French has brought her lifelong influences from ‘70s soul and R&B into her wide-ranging and powerful work as a singer, songwriter, poet and theater artist. After she approached The Saint Paul Chamber Orchestra for a possible collaboration, she embarked on her first foray into concert music in 2018 with A Requiem for Zula, an orchestral song cycle that honored her late mother.

When SPCO supporters Bill and Susan Sands decided to commission a new work for the orchestra in honor of their fiftieth anniversary, they entrusted French with the assignment and encouraged her to respond to the commission in any way that was meaningful for her. French worked on the resulting score, The Sands of Time, in a world before the Covid pandemic, and before the murder of George Floyd, events that have only deepened her resolve to use her music in service of human connection and justice. As in her first piece for orchestra, French collaborated with the arranger Michi Wiancko, but after steeping herself in the principles of orchestration and the ranges of concert instruments, French took on the responsibility of distributing her music into the orchestral parts herself, using her keyboard to record layer upon layer in Apple’s GarageBand software.

Through meetings where she got to know Bill and Susan Sands, French was inspired to have her first movement deal most directly with romantic love. From the beginning of this song that shares its punning title with the cycle as a whole, “Sands of Time,” French speaks to us, the audience, as a knowing guide: “I’ve been thinking, y’all,” she sings, “about what love has taught me this far.”

The second song, “Give Me Your Love,” pivots to an interrogation of what disrupts love — a sentiment inspired specifically by the former president. “Your finite words of hurt and hatred won’t pollute my mind or change my hope for unification,” she sings. As an orchestral interlude takes flight, she invites us along, shouting, “Hold on y’all! Change is coming!”

In an interview, French spoke about how, in the years since the deaths of her parents, she has been on a journey “to love myself and to like myself, and to understand why I am the way I am, and be investigative and introspective, and to unlock core memories and fully love my whole, total being.” She articulates aspects of this brave emotional work in the third song, “Breaking Free,” where she sings, “It’s overwhelming to have to look so deep inside. I wanna break free from my iniquity.”

The next selections explore other facets of love that animate French’s life and music: “the love for my freedom of thought and freedom of speech, and the persistence of life. I was thinking about all the ways that love works, whether it is platonic or romantic or agape.” The sense of freedom comes through in the fifth song, “Me Being Me (Is Revolutionary).” A celebratory song, “The Dance of Life,” encourages us all to “be ambitious and assertive in the dance of life. There’s no room for any fear with an aura that’s so bright.” After an instrumental dance interlude, the cycle closes with a reprise of “Sands of Time,” bringing this journey of love back to its interpersonal point of origin.

French spoke about how much she learned from her mother, an educator and community activist, and her father, whom she described as “more hotheaded and political” and deeply involved in community action. As she sees it, “People can hear the truth if you can give it to them in a way that they can hear it. The way I approach music is that I am going to make it so beautiful and so lush and so honest and vulnerable and authentic that you have to hear it.”

Aaron Grad ©2022

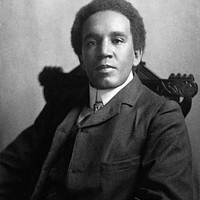

Samuel Coleridge-Taylor received the last part of his name from his father, who had returned home to Sierra Leone (the British colony in Africa originally established as a refuge for those who’d been freed from or escaped enslavement) without learning that a white British woman was pregnant with his son. Samuel’s mother gifted her son with an auspicious name modeled after the English poet Samuel Taylor Coleridge, and the boy’s grandfather passed on an even greater gift by introducing Samuel to his own instrument, the violin.

Coleridge-Taylor went on to enroll at London’s Royal Academy of Music at the age of 15 as a violinist, and three years later he began composition lessons as well. But even then he was already a published composer, and the Nonet he wrote in 1893, during his first year of formal composition study, shows how far he had already come in absorbing the styles of his heroes, Johannes Brahms and Antonín Dvořák. It was only in later years that Coleridge-Taylor channeled African and African American themes into works that proved hugely influential for future generations of American composers, a project that was still gathering steam when he died of pneumonia at the age of 37.

Coleridge-Taylor showed quite a bit of originality in his Opus 2 by assembling a non-standard nonet of oboe, clarinet, bassoon, horn, violin, viola, cello, bass and piano. Mixed ensembles of strings and winds had been popular since the time of Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart and Ludwig van Beethoven, and there was ample chamber music from the past century combining piano with strings or winds, but this particular configuration of winds, strings and piano added a new level of sonic complexity that the young composer handled with aplomb. The musical materials could easily be mistaken for the themes and harmonies of Brahms or Dvořák, which is quite admirable for the work of a British teenager, and the four attractive movements make a strong case for the enormous talent that allowed Coleridge-Taylor to become a trendsetter and role model.

Aaron Grad ©2022

Get driving directions and find nearby parking.

Find dining options close to the venue.

View seating charts to find out where you'll be seating.

SPCO concerts are made possible by audience contributions.

For exclusive discounts, behind-the-scenes info, and more:

Sign up for our email club!