Steven Copes Plays Brahms’ Violin Concerto

Before Richard Strauss fell under the spell of Richard Wagner’s music at age seventeen, his most impactful mentor was his own father. Franz Strauss, the principal horn player in the Munich court orchestra, earned a reputation as one of the finest performers ever on his instrument. He was also a composer and a conductor, leading an amateur orchestra that gave his son a proving ground for his earliest attempts at orchestration.

The Serenade for winds that Richard Strauss composed in 1881 aligned with the Classical style championed by his father. The title reflected the eighteenth-century tradition of light music for an evening gathering, and the instrumentation resembled Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart’s Serenade No. 10 (“Gran Partita”) for thirteen players. The Serenade was the first piece by Strauss to be performed outside of Munich, and it remains among the earliest of his works in the active repertoire.

The Serenade enters at a relaxed Andante tempo, introducing its first theme in a chorale of balanced, gentle chords. Throughout the single movement, the scoring is impeccably clear and balanced, proving that the teenaged Strauss made the most of the knowledge and access offered by his father. Franz Strauss must have been especially proud of the warm and regal music his son wrote for the ensemble’s four horns.

Aaron Grad ©2023

Coleridge-Taylor Perkinson was destined to be a composer from birth, when his mother, a pianist and organist, gave him that hyphenated name in honor of the Black British composer Samuel Coleridge-Taylor (whose name was itself a tribute, derived from the British poet Samuel Taylor Coleridge). Perkinson gained entry to New York’s legendary High School of Music and Art as a dancer, but he took up composing during his time there and earned a top music prize before he graduated. He went on to study music at the Manhattan School, Princeton University and the Berkshire Music Festival (now called Tanglewood), and he also studied conducting in Europe. As part of a rich professional life centered in New York, Perkinson co-founded the Symphony of the New World in 1965, the first racially integrated orchestra in the country, and he served for a time as music director of the Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater. Perkinson composed his Sinfonietta No. 2 (subtitled “Generations”) in 1996 for the Manchester Music Festival in Vermont. He wrote the following program note:

The inspiration for this composition, though non-programmatic, is somewhat autobiographical in that it represents my attempts at what were and are my relationships to members of my family — past and present. While each of the movements is without a strict “formal” mode, an informal analysis of their structures is as follows:

I. Misterioso and Allegro (to my daughter) is based on two motifs: the B-A-C-H idea (in German these letters represent the pitches B-flat, A-natural, C-natural, and B-natural), and the American folk tune “Mockingbird,” also known as “Hush Li’l Baby, Don’t Say a Word.”

II. Alla sarabande (sarabande, a 17th- and 18th-century dance in slow triple meter) is dedicated to the matriarchs of my immediate family (of which there were for me, three), each of whom contributed a unique form of guidance for life’s journey.

III. Alla Burletta (to my grandson). A burletta is an Italian term for a diminutive burlesca or burlesque-type work — a composition in a playful and jesting mood. Thematically, this movement is based on the pop tune “Li’l Brown Jug.”

IV. Allegro vivace. This movement is a loosely constructed third rondo which thematically begins with a fughetta (original melody), has a second theme (African in origin), and a third theme (“Mockingbird” paraphrased). Once again, the B-A-C-H idea from the first movement is the musical thread that ties these elements together.

Aaron Grad ©2023

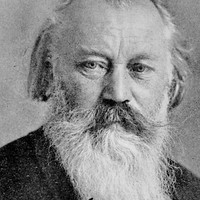

Johannes Brahms was at the impressionable age of 15 when a revolution in Hungary sent refugees fleeing to the United States, many of them embarking from Brahms’ native Hamburg. Brahms fell in love with the Hungarian music that flooded his city, brought by the likes of violinist Ede Reményi, and so it was both a tremendous honor and a lucky career break when that same musician returned five years later and hired the 20-year-old Brahms to accompany him on the piano during a tour through Germany. During that tour, Brahms met another Hungarian violinist, Joseph Joachim, who at 22 was already at the start of an impressive career. Joachim’s first great kindness to Brahms was to introduce him to Robert Schumann, sparking the brief mentorship that helped Brahms foster his passion for the formal models perfected by Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, Ludwig van Beethoven and Felix Mendelssohn.

Brahms and Joachim remained friends for most of their lives (apart from a falling out surrounding Joachim’s divorce), and the one and only Violin Concerto that Brahms composed in 1878 stands as a testament to their strong working relationship. Brahms mailed drafts to Joachim to consult on the solo part, and the violinist ended up supplying the enormous cadenza for the first movement that many performers still use. They debuted the work together in Leipzig on January 1, 1879, with Brahms conducting the Gewandhaus Orchestra.

On that same program, Joachim also performed the Violin Concerto by Beethoven, about whom Brahms once wrote, “You can’t have any idea what it’s like always to hear such a giant marching behind you!” Once Brahms hit his stride with orchestral music in his forties, he did not shy away from writing works that paralleled those of his idol, and he even seemed to embrace the implicit comparison at times, like when the solo violin enters his concerto over an exposed timpani roll, recalling the prominent timpani strikes that begin Beethoven’s concerto. Brahms also followed Beethoven’s lead in how the first movement’s solo cadenza releases into music of great delicacy and beauty, instead of a loud and blustery conclusion.

The central Adagio movement presents one of Brahms’ loveliest melodies, which ironically comes from a solo oboe, not the violin soloist. (This shared spotlight prompted the violinist Pablo de Sarasate to quip, “Would I stand there, violin in hand, while the oboe plays the only melody in the whole work?”) The violin does take up a version of the theme, but it migrates from F-major to the stormier key of F-sharp-minor. By the time it returns for a closing passage in F-major, only wisps of the original melody remain.

The concerto concludes with a rowdy finale built from a theme with a Hungarian flavor. That motive, voiced in thirds and following a rising and following contour, sounds quite similar to the main theme from the finale of Max Bruch’s Violin Concerto No. 1, composed ten years earlier, and also edited and premiered by Joachim.

Aaron Grad ©2023

Get driving directions and find nearby parking.

Find dining options close to the venue.

View seating charts to find out where you'll be seating.

Get driving directions and find nearby parking.

Find dining options close to the venue.

View seating charts to find out where you'll be seating.