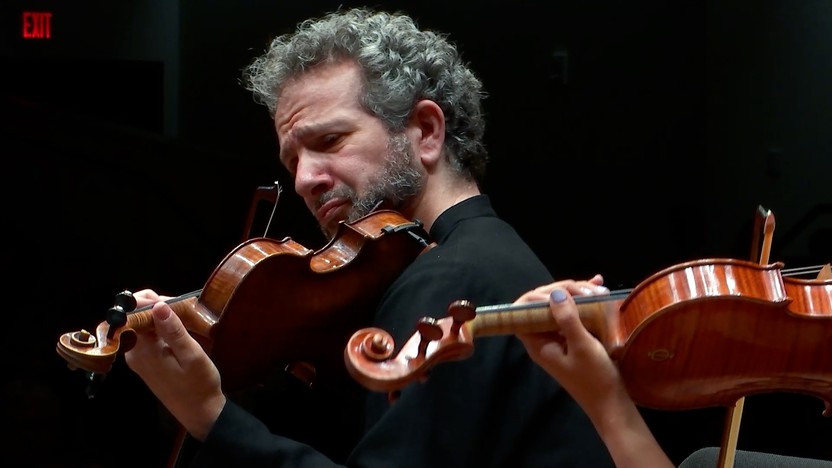

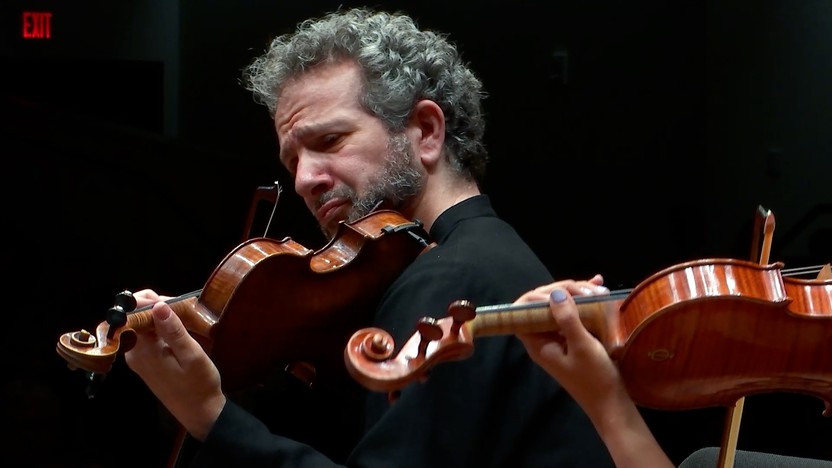

Steven Copes Plays Prokofiev’s First Violin Sonata

Zoltan Almashi is a leading figure in the musical life of Ukraine, both as a cellist in the Kyiv Camerata and in his own quartet, and also as the composer of more than 70 concert works. After Russia’s full-scale invasion in 2022, the Ukrainian conductor Oksana Lyniv invited Almashi to compose a work for string orchestra that would use Samuel Barber’s iconic Adagio for Strings as a reference point. Working amid the ongoing war, Almashi used that prompt to create Maria’s City, a work he dedicated to the Ukrainian city of Mariupol that was besieged and largely destroyed before being occupied by Russian forces. (The city’s name is linked to the Virgin Mary and the small Greek Orthodox population in the region that has endured there since the Middle Ages.)

“For me,” Almashi explained in an interview with the Ukrainian music journal The Claquers, “the title and dedication are more important than the work itself. Humanity forgets everything very quickly. It forgets the facts surrounding terrible crimes, and they need to be reminded of these facts. Every normal musician is interested in title and dedication of works they play, and the title and the dedication of Maria’s City are the keys to remembrance.”

Aaron Grad ©2025

Working for the musically ravenous Prince Nikolaus Esterházy and spending much of each year at a remote country palace, Joseph Haydn acknowledged that he “was forced to become original.” One new direction he explored in the late 1760s and early 1770s was the Sturm und Drang (“Storm and Stress”) aesthetic that was also cropping up in the theater, literature and artwork of the time. This tendency toward heightened emotion and drama led Haydn to compose symphonies in minor keys for the first time; he completed seven of them in that period, including the Symphony No. 44 in E Minor that he finished by 1772.

Haydn purportedly asked for the slow movement of this symphony to be played at his funeral, and even though no such memorial performance took place, it was enough to attach the nickname of “Mourning” to the work. The opening Allegro con brio movement emphasizes tense dissonances that yearn to resolve toward more settled tones, and then the E-minor tonality carries over to the Menuet, built as a canon in which the bass instruments follow a measure behind the violins.

The Adagio third movement is the least mournful music in this symphony, with its long, arcing phrases delivered by muted strings in the sweet key of E-major. The turbulence of E-minor returns for a brisk finale filled with unison exclamations that echo the texture of the opening movement.

Aaron Grad ©2025

The arrangement of Violin Sonata No. 1 is made possible by support from Michael Hostetler and Erica Pascal.

Sergei Prokofiev settled in Moscow in 1936, nearly twenty years after he left Russia in the wake of the October Revolution of 1917. As an expatriate in Europe, he had found himself increasingly at odds with strident, modern tastes; meanwhile, Soviet audiences and authorities proved receptive to the composer’s “new simplicity,” as he dubbed his developing style. A string of successful film score and ballet commissions enticed Prokofiev back to his homeland on a permanent basis, and he entered the stream of Soviet music firmly established as a star.

The Violin Sonata No. 1 in F Minor demonstrates how Prokofiev’s applied his clear and forthright style in music of the heaviest emotions. He began the score in 1938, amid the Great Purge in which Stalin killed or displaced millions of supposed enemies. Having stalled out after two movements, Prokofiev returned to the sonata in 1943, in the midst of World War II, and he finally finished it in 1946.

The four-movement structure, alternating slow and fast movements, rekindles a tradition from early in the history of violin sonatas, as modeled by Arcangelo Corelli and George Frideric Handel. The slow first movement dominates the mood of the sonata, especially when its material returns to give the finale a slow ending, conveying a sound that Prokofiev likened to “wind in a graveyard.” After Prokofiev died in 1953 (on the very same day as the man who had become his tormentor, Joseph Stalin), the violinist for whom the sonata was written, David Oistrakh, played portions of it at the composer’s funeral.

In this new version commissioned by The Saint Paul Chamber Orchestra, the composer and pianist Stephen Prutsman (an SPCO Artistic Partner from 2004 to 2007) orchestrated Prokofiev’s piano part to convert this sonata into a dramatic concerto.

Aaron Grad ©2025

The arrangement of Violin Sonata No. 1 is made possible by support from Michael Hostetler and Erica Pascal.

Get driving directions and find nearby parking.

Find dining options close to the venue.

View seating charts to find out where you'll be seating.

SPCO concerts are made possible by audience contributions.

For exclusive discounts, behind-the-scenes info, and more:

Sign up for our email club!