Vivaldi's Echo Concerto

Sponsored By

- February 28, 2020

- February 29, 2020

Sponsored By

After studying violin in his native Rome with Corelli, Pietro Castrucci (1679–1752) moved to London, where he served as the concertmaster for Handel’s opera orchestra. Published in 1736, Castrucci’s Concerto Grosso in D (Opus 3, No. 12) follows Corelli’s concerto grosso template, with a solo group of two violins and cello playing against a larger ensemble of strings and basso continuo. The most distinctive musical feature comes in the finale, when the three solo parts contribute echoes of the phrases played by full string sections.

Aaron Grad ©2019

With the release of her debut album on ECM Records, the Bulgarian-born composer Dobrinka Tabakova (b. 1980) earned a Grammy nomination in 2014. That disc closes with the string septet Such Different Paths (2007–2008), which emerged from “the underlying idea of music as building blocks,” with the intention that “there is the sense of a journey,” as she explained in a program note. The many echoes and canons in her music align Tabakova with other European minimalist composers who have drawn on centuries of sacred music in their cyclical structures.

Aaron Grad ©2019

Antonio Vivaldi (1678–1741) grew up in Venice, the epicenter of the musical echo. Ever since the wealthy city-state completed Saint Mark’s Basilica in the eleventh century, that church was an eternal hotbed for musical innovation — partly out of necessity. The great distances between the choir lofts made it all but impossible to perform in unison as church singing grew more complex, and so Venetian composers compensated by developing new forms of antiphony, with multiple choirs singing against each other from separate locations. Composers on the Saint Mark’s payroll in the early 1600s included Giovanni Gabrieli and Claudio Monteverdi, and their towering achievements shaped the education of Vivaldi and all other musicians within Venice’s vast reach for centuries.

On the score to the Concerto in A, RV 552 (1740), Vivaldi wrote “Per eco in lontano,” an indication for several of the lines “to echo in the distance.” In the Allegro first movement, the antiphony begins with an “echo” soloist and two accompanying violins repeating the primary soloist’s full theme. The length of the echo compresses and expands throughout the movement, and the treatment of the echo device becomes more liberal, like when the lead violin provides its own echo by alternating between forte and piano dynamics.

Aaron Grad ©2019

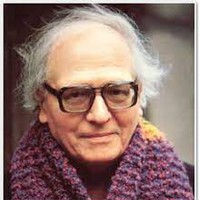

When the French composer Olivier Messiaen (1908–1992) was invited to write a work marking the United States’ Bicentennial, he traveled to Utah’s Bryce Canyon and other natural landmarks. Over the next three years, he produced a 100-minute work for orchestra, From the Canyon to the Stars (1971–1974), including a movement for solo horn adapted from a recent piece composed to memorialize a former student. Besides the manmade echoes written into this “Interstellar Call”, the spacious solo draws attention to the natural echoes of any acoustic environment.

Aaron Grad ©2019

The three symphonies that Joseph Haydn (1732–1809) composed in November of 1784 appear to have been tailored to the publishing market, and he found outlets for them in Vienna, Paris, London, Berlin and Amsterdam, attesting to his growing international fame. The Symphony No. 80 in D Minor (c. 1784) from that group is one of only ten symphonies that Haydn set in a minor key, but this one exhibits none of the angst that marked his earlier Sturm und Drang (“Storm and Stress”) phase. The symphony’s cheeky sense of humor is rooted in the manipulations of time and space that create sudden contrasts and whimsical juxtapositions, like when the first movement’s development section begins with two full measures of silence, followed by a restart of the previous theme in a new, unrelated key. These spatial effects don’t rely on obvious echoes, but they owe as much to past generations of antiphonal trailblazers as the more subtle canons and loudsoft alternations that enliven the entire symphony’s intricate orchestration.

Aaron Grad ©2019

Get driving directions and find nearby parking.

Find dining options close to the venue.

View seating charts to find out where you'll be seating.

SPCO concerts are made possible by audience contributions.

For exclusive discounts, behind-the-scenes info, and more:

Sign up for our email club!