Anthony McGill Plays Mozart’s Clarinet Concerto

(Duration: 14 min)

Benjamin Britten had a precocious start in music, studying piano and viola and composing hundreds of works by the time he was a teenager. At fourteen, Britten’s viola teacher introduced him to the composer Frank Bridge, who agreed to give Britten private lessons. “I, who thought I was already on the verge of immortality, saw my illusions shattered,” Britten later wrote about his course of study with Bridge, a demanding teacher who fostered the rigorous technique needed to round out Britten’s natural inventiveness. Britten went on to enroll at the Royal Conservatory of Music in 1930, and even if he chafed at the conservative approach of his teachers, he was able to fill in the gaps by devouring recent music by Stravinsky, Schoenberg and other modernists.

Britten’s career began to take off in 1932, when a prize-winning Phantasy for string quartet led to his first professional performance. That same summer he took three weeks to compose the Sinfonietta, the work that would become his first published opus. The scoring for ten solo instruments (a woodwind quintet plus a string quintet) reflects the influence of Schoenberg’s First Chamber Symphony, a seminal work for such mixed ensembles. The dissonant harmonies and spiky phrases in the opening movement also point to young Britten’s fascination with Continental modernism, but still the music retains Britten’s intuitive feel for melody, as heard in the mellifluous woodwind phrases and crystalline violin duet in the central movement. A trembling viola line links directly to the Tarantella, a kinetic finale in the manner of the Italian folk dance named, so it is said, for the manic gyrations intended to ward off death after the bite of a tarantula.

Aaron Grad ©2023

(Duration: 25 min)

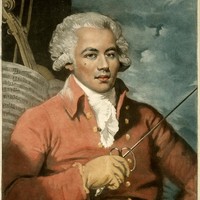

Joseph Bologne, Chevalier de Saint-Georges, was a champion fencer before his twentieth birthday. He was also a renowned boxer, dancer and marksman, but his real love was music, and his prowess with the violin allowed him to become the leader of a powerhouse orchestra in Paris and a personal instructor to Marie Antoinette. She nominated him to become music director of the Paris Opera in 1776, but the prejudices he had transcended up to that point finally proved to be too strong: the prima donnas at the opera refused to sing for a mixed-race maestro.

Bologne’s French father owned sugar plantations on the Caribbean island of Guadeloupe, and he amassed incredible wealth through the forced labor of enslaved Africans, including the woman who gave birth to the future star of French music. Going against the code that normally would have passed enslaved status from mother to son, Bologne was raised openly as his father’s child, and from the age of 13 he received the finest aristocratic education available in France.

His father’s death in 1774 meant that Bologne had to start supporting himself financially, and he leaned into the growing popularity of his published sheet music. For this concerto from around 1775, besides surely performing it himself, he arranged for it to be printed as part of pair of violin concertos published in Paris as his Opus 5. The version heard here, created by the composer Derek Bermel for Anthony McGill, adapts the solo violin part for the clarinet, an instrument that was just on the cusp of finding its foothold as a solo instrument in Bologne’s day — a process that reached fruition in the next decade through the efforts of Mozart.

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart often comes up in discussions of his slightly older contemporary Bologne, and for too long Bologne was known condescendingly, if at all, as the “Black Mozart.” In fact it was Mozart who was a fan and imitator of Bologne — certainly after hearing him firsthand on his trip to Paris in 1777, and maybe even before that through the published music. Bologne was a master of the pleasing galant style that Mozart adopted in his own violin concertos from his teenage years, and even the savviest listener might mistake this Bologne concerto for one of Mozart’s. In the first movement, after the string orchestra completes its first full pass through the themes, the soloist enters over a transparent texture that holds back the lower strings, placing the spotlight on the long lines and agile leaps that transfer so well to the clarinet.

Bologne published the slow movement as a Largo, but Bermel (like many other modern interpreters) speeds it up to an Andante that brings out the songlike qualities of the elongated lungfuls of melody and bouncing triplet rhythms. As in the first movement, Bermel filled in the space for the improvised cadenza with his own written version, leaning on his expertise as an elite clarinetist.

In the Rondo finale, contrasting episodes based around a droning minor key raise the fascinating question: had the teenaged Mozart seen this score when, in the same year Bologne’s was published, he wrote his own violin concerto in the same key of A-major, with a rondo finale that also veered into a droning “Turkish” episode in A-minor? Whether coincidental or not, it speaks to how well Bologne embodied the trends of the day.

Aaron Grad ©2023

(Duration: 30 min)

The music that Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart wrote for his friend Anton Stadler, a clarinetist and fellow freemason, was instrumental in establishing the clarinet as an equal to its older cousins in the woodwind family. Mozart’s first composition for Stadler was the “Kegelstatt” Trio from 1786, scored for clarinet, viola and piano. (Mozart played the viola part himself.) Next came a quintet for clarinet, two violins, viola and cello, completed in 1789. This work required a basset clarinet in the key of A, an instrument with a low-range extension designed by Stadler. Mozart went on to write Stadler a concerto featuring the same instrument, completed two months before the composer’s untimely death.

The Clarinet Concerto in A Major demonstrates Mozart’s keen understanding of the solo instrument’s range and agility. The tonal quality of the clarinet changes through its range, from the deep resonance of the bass notes, through the warm and hollow midrange of the chalumeau register, and up into the brilliant clarity of the highest octaves. At certain points in the fast opening movement, the soloist seems to play several opera characters engaged in dialogue, leaping from range to range; other times, a single scale or arpeggio journeys across all four octaves of the instrument’s compass.

In 1785, a critic wrote of Anton Stadler, “One would never have thought that a clarinet could imitate the human voice to such perfection.” Judging by the slow movement penned expressly for Stadler, Mozart surely agreed!

The finale has a bit of Haydn’s sense of humor in it, as in the playful held notes of the main theme that draw out unresolved tension. The episodic structure of the Rondo allows for fanciful and dramatic excursions, making each return to the familiar music all the more delightful.

Aaron Grad ©2023

Get driving directions and find nearby parking.

Find dining options close to the venue.

View seating charts to find out where you'll be seating.

Get driving directions and find nearby parking.

Find dining options close to the venue.

View seating charts to find out where you'll be seating.