Brahms’ Second Sextet

The Jewish-Czech composer and pianist Erwin Schulhoff was a prodigy who gave his first concert tour of Germany at the age of sixteen. After four years of forced military service for Austria during World War I, Schulhoff emerged with strong leftist politics and musical interests ranging from Arnold Schoenberg’s atonality to American jazz. His career options in Berlin shriveled as the economic collapse and anti-Semitic tide brought the Nazi party to power, and he fared even worse in Prague, where he was eventually arrested and transferred to a concentration camp in 1941. He died there eight months later while still attempting to finish his Eighth Symphony.

Schulhoff was a real trickster who loved to poke fun at anything that could be considered self-important or pretentious. His Five Pieces for String Quartet from 1923 ape the customs of the Baroque dance suite, starting with a parody of a Viennese waltz that jumbles the expected three-beat pulse while also jesting at the elitist trends emanating from the “Second Viennese School” of Schoenberg and company. The ironic Serenade style of the second piece seems pointed at the “night music” of Béla Bartók, who also exerts on influence on the energetic third dance in the style of Schulhoff’s Czech homeland. The tango follows the lead of Igor Stravinsky and other high-art composers who adopted that South American dance craze. The final piece in the style of a tarantella updates a manic folk dance from Italy that, legend has it, could ward off the deadly effects of a tarantula’s venom — a musical style and backstory that captured the attention of many Romantic-era composers.

Aaron Grad ©2024

André Caplet’s relatively brief career began with a boost in 1901 after winning the prestigious Rome Prize on his first try, just as he finished his studies at the Paris Conservatory. That same year he composed the Suite persane for the Modern Society of Wind Instruments, a laboratory for contemporary woodwind ensemble music spearheaded by the influential flutist Georges Barrère. Caplet went on to become a friend and confidant of Claude Debussy, called upon to proofread the older composer’s scores; Debussy even entrusted Caplet to orchestrate several works. He might have been the French composer to carry the mantle of modernism forward into the twentieth century had he not died at the age of 46 from lung damage he sustained during gas attacks in World War I.

Caplet’s “Persian Suite” aligns with the fascination among French artists and intellectuals for all things “exotic,” especially in the wake of the 1889 Universal Exposition that brought unexplored cultures from all over the world to Paris. The movement headings in ersatz Persian and melodic tropes built from scales of a general “oriental” character are not meant to be faithful reproductions of a foreign culture, but rather an opening into a fantasy soundscape that offered an alternative to the old forms of musical discourse and logic. The first movement’s melody is first presented in bare octaves, removing Western harmony from the equation entirely, and the second movement introduces its theme harmonized in parallel fifths, another sound that has been stereotyped as Asian (and one which is strictly forbidden in common tonal practice). In the energetic third movement, Debussy’s beloved whole-tone scales appear alongside semitic modes.

Aaron Grad ©2024

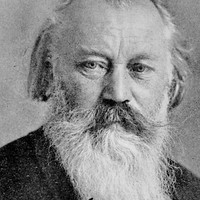

Johannes Brahms wanted desperately to live up to the promise his late mentor Robert Schumann had seen in him as a budding master of the orchestra, but first the young composer had to find a way to make his reverence for music of the past an asset, rather than an obstacle. The shadow that darkened his path most frighteningly was that of Ludwig van Beethoven, and it was not until he was in his forties that Brahms found his footing with two of Beethoven’s signature genres, symphonies and string quartets.

To get there, Brahms built his confidence in formats that were less laden with baggage, including two serenades for small orchestras in the late 1850s, and the first of his string sextets in 1860. There were very few precedents for an ensemble of two violins, two violas, and two cellos — just a handful from the previous century by the cellist-composer Luigi Boccherini, and a more recent effort from Louis Spohr — and the rich scoring suited Brahms well, who was developing a signature sound based on superimposed, interlocking layers of music.

Brahms returned to that string sextet configuration in 1864, drawing from source material that dated back to the 1850s. He even included a veiled reference to his personal history by encoding the name of the fiancé he split with in 1859, Agathe von Siebold, represented by the pitch sequence A-G-A-(t)H-E (The German “H” is known in English as B-natural). The first movement shades the G-major tonality with foreign sounds from the distant key of E-flat, creating a dark and mysterious harmonic framework. Meanwhile the melodies progress with utmost economy, elaborating the crisp leaps and arpeggios of the opening measures. Brahms, wasting nothing, even milked the melodic possibilities of the initial accompaniment figure of a slow trill.

All those flashes of E-flat major in the first movement, reappearing up to the very end, have the effect of pushing the G-major home key toward its more somber twin, G-minor. (E-flat is native to G-minor, but not G-major.) In the scherzo that arrives as the second movement, a key setting of G-minor confirms this sextet’s tendency to drift into stormy waters. Transparent textures, crisp counterpoint and dry pizzicato (plucking) impart a sly, devilish charm to the movement, and a contrasting passage of boisterous dance music ensures that the minor-key escapades are all in good fun.

This ongoing conflict of major and minor harmony holds sway in the slow movement as well, built as a theme-and-variations that lays out its initial material in an unrooted setting for two violins and viola, postponing a solid arrival in the new key of E-minor. The masterful variations pick apart the subtle ambivalence at the heart of this musical material, until the earlier glints of E-major take hold for a sweet conclusion.

By this point, we should not be at all surprised that the finale teases us with a minor-key flourish at the beginning. It ultimately resolves all the amassed tension with a warm and hearty arrival in G-major, taking full advantage of the large ensemble and its orchestra-like body of sound.

Aaron Grad ©2024

Get driving directions and find nearby parking.

Find dining options close to the venue.

View seating charts to find out where you'll be seating.

Get driving directions and find nearby parking.

Find dining options close to the venue.

View seating charts to find out where you'll be seating.