Flights of Fancy

In 1977, a group of Finnish student composers at the Sibelius Academy founded Korvat auki—the Ears Open Society. Frustrated by what they felt was their country’s stiflingly provincial musical culture, these young composers voraciously sought out music from outside Finland, from the scores of the Second Viennese School to the avant garde of their own time.

The initiative and curiosity demonstrated by the composers of the Ears Open Society—meeting independently in bars and in one another’s apartments to discuss and analyze their musical findings, and eventually producing their own concerts in venues ranging from kindergartens to prisons—are evident in their mature work. The most prominent of these—Magnus Lindberg, Esa-Pekka Salonen, and Kaija Saariaho—have become regarded among the most sonically inventive composers of their generation and achieved considerable international renown. This season, Saariaho’s L’Amour de Loin will be the first opera composed by a woman to be staged at the Metropolitan Opera since 1903.

Saariaho’s musical language is strikingly visceral, characterized by a keen ear for timbre and evocative sounds often achieved through unconventional (and notably difficult) instrumental techniques. Her Terrestre is scored for solo flute and an economically brilliant ensemble of percussion, harp, violin, and cello. The work is based on the second movement of her own flute concerto Aile du Songe (Wing of Dream); both titles come from Oiseaux, a collection of poems by Saint-John Perse.

Terrestre comprises two distinct sections. The composer writes: “The first section of Terrestre, ‘Oiseau dansant,’ introduces a deep contrast with the other material of the concerto. It refers to an Aboriginal tale in which a virtuosic dancing bird teaches a whole village how to dance. The second section [‘L’Oiseau, un satellite infime’] is a synthesis of all the previous aspects, then the sound of the flute slowly fades away…”

Terrestre was commissioned by Eleanor Eisenmenger in honor of Kaija Saariaho’s fiftieth birthday.

Patrick Castillo ©2016

This work was co-commissioned by Nagoya Philharmonic Orchestra and The Saint Paul Chamber Orchestra, with soloist Claire Chase in mind. There are two versions of this concerto, one with orchestra and one with ensemble, with same solo part.

I knew that there will be two versions to this concerto while I was composing this work, so I focused on relationship between solo and orchestra: how the solo part would be related to the bigger orchestra and how the same part would also relate to the intimate ensemble. Each version should give a very different impression, even though the solo part is the same.

This concerto has 5 sections and the soloist uses 4 flutes: C flute, piccolo, contrabass flute and bass flute.

The beginning section is sort of an introduction, where solo flute will play the delicate variety of sounds with very limited pitches, while the orchestra/ensemble plays light tremolo, pizzicato, and the percussion section plays several handheld instruments, like the sea-shell chimes and so on (the kind of instruments you might find in a toy store, or a hotel gift shop) to give it a playful feel. All are played extremely gently, while vibraphones (piano, for ensemble version) are playing pianissimo, acting as "reverb" of the whole sound.

Then there will be an extremely active dance-like section with C flute, with a very vertical orchestra part that is spiky and accentuated together with the solo flute line. Next, the flute soloist plays while singing glissandi downwards and the orchestra chords melt into this sound. It gives the impression that the flutist is playing into a ring modulator and turning the nobs while playing.

For the piccolo section, I wanted to do something opposing the instrument. I wrote the piccolo part to be played almost entirely in the lowest octave of the instrument, while the whole orchestra is pitched above the solo line, extremely quietly.

This concerto has a proper cadenza. The only slightly unusual thing is that this cadenza is played on contrabass flute.

The final section is like a chorale. The soloist plays on bass flute, and the orchestra plays gentle, lyrical texture with microtones, which are derived from a series of distorted harmonics shared by the soloist and orchestra, like the ghost of the whole concerto.

Dai Fujikura ©2015

The English composer, pianist, and conductor Thomas Adès has distinguished himself as something of a modern-day wunderkind in the contemporary classical music landscape. Still in his early forties, he has already penned numerous acknowledged masterpieces across genres, from solo and chamber music to symphonic and operatic works; received commissions from such leading orchestras and institutions as the Berlin Philharmonic, Los Angeles Philharmonic, and Carnegie Hall; appeared as pianist and conductor on the world’s most prestigious stages; and is the recipient of the 1999 Grawemeyer Award (for Asyla), the Grammy Award for Best Opera Recording (as conductor of his own opera The Tempest, with the Metropolitan Opera), and other honors.

Adès’s rapid rise to such renown is rooted in his having honed a distinctly personal compositional language and technique from the beginning of his career: structurally sure-handed, colorfully detailed—and, writes British musicologist Arnold Whittall, “often [alluding] to specific models while nevertheless keeping its distance from them.”

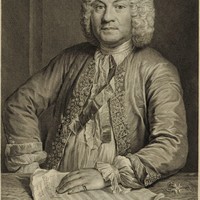

One particularly cherished model has been the French Baroque master François Couperin. Adès claims, “My ideal day would be staying home and playing the harpsichord works of Couperin—new inspiration on every page.” His Three Studies from Couperin—one of several works borne of said inspiration—are orchestrations of three short movements from Couperin’s extensive catalogue of music for harpsichord. The titles—Les Amusemens, Les Tours de Passe-passe, L’Âme-en-peine—are Couperin’s. “In composing these pieces,” Couperin noted, “I have always had an object in view, furnished by various occasions. Thus the titles reflect my ideas; I may be forgiven for not explaining them at all.”

While the allusion to a specific model is perfectly explicit, the distance from Couperin is here created by Adès’s ingenious deployment of the orchestra. It is as if a familiar old movie has been psychedelically Technicolored, resulting in a musical statement that is irrepressibly modern—and irrepressibly Adès’s—despite its eighteenth-century source material. The first movement’s pillowy texture owes to the combination of alto and bass flutes, muted strings, and marimba; the clang of anvils delightfully piques the ears. Adès highlights Couperin’s lithe “sleight of hand” with impish interjections of brass and percussion. The suite’s somber finale illustrates “the soul in torment,” but one likewise outfitted in resplendent color.

Patrick Castillo ©2014

Respighi’s scholarly interest in early music frequently informed his compositional activities. Between 1917 and 1931, he produced his Antiche danze ed arie (Ancient Airs and Dances), a set of three orchestral suites based on Italian lute music of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries (see p. 24). His orchestral work Gli uccelli (The Birds) likewise turns to music of the past. Its five movements are based on music by Jean-Philippe Rameau, Bernardo Pasquini, and other seventeenth- and eighteenth-century composers.

After a regal opening, the Preludio, based on music by Pasquini, introduces a veritable musical aviary. Various instruments throughout the orchestra, in turn, colorfully mimic birdcalls, prefiguring later turns in the spotlight by the hen and the cuckoo. Respighi’s orchestration is delicate throughout. Against a quiet gust of bassoons, horns, and low strings, the violins take flight before a final reprise of the movement’s opening measures.

The oboe, marked piano, dolce, espressivo, gives tender voice to La colomba (“The Dove”), based on a lute song by the French lutenist and composer Jacques de Gallot. Harp and muted strings accompany the tune, accented by quietly twittering violins.

La gallina (“The Hen”) follows the dove’s sublime song with a measure of comic relief. Respighi sets this music—originally a keyboard work by Rameau—in piquant colors. The strings’ quiet staccato pecking (played arco saltato, bouncing the bow on the string) is interrupted by fortissimo exclamations, evoking the hen’s squawk. Respighi adds to this the pungent double-reed timbre of oboe and bassoons, and the strident sound of muted trumpets.

The moonlit fourth movement, L’usignolo, is based on music by an anonymous seventeenth century English composer. Respighi depicts the nightingale in soft, mysterious hues. A sustained horn pedal and hushed strings buoy the featherweight flute melody, as unassuming as a nursery rhyme. A touch of celesta conjures twinkling stars.

Respighi saves the work’s most dazzling colors for the final movement, Il cuccù (“The Cuckoo”), based on Pasquini’s Toccata con lo Scherzo del Cucco for harpsichord (1702). Throughout the movement’s subtly contrasting episodes, swirling lines in winds, strings, and celesta dance gleefully around the persistent descending-third cuckoo calls. The work ends with a satisfied recollection of the regal music of the Preludio.

Patrick Castillo ©2016

Get driving directions and find nearby parking.

Find dining options close to the venue.

View seating charts to find out where you'll be seating.

SPCO concerts are made possible by audience contributions.

For exclusive discounts, behind-the-scenes info, and more:

Sign up for our email club!