Jonathan Biss Plays Beethoven’s Emperor Concerto

Sponsored By

Sponsored By

From the time Beethoven arrived in Vienna in 1792, he enjoyed a reputation as the leading keyboard virtuoso in the Imperial capital, filling the absence left by Mozart’s death a year earlier. While Beethoven worked toward his grand ambitions to compose symphonies and operas, he pieced together a freelance livelihood by composing, performing, publishing, teaching and cultivating well-to-do patrons. He honored one such patron, the Russian emissary Count Johann Georg von Browne, with the dedication of his three string trios published in 1798 as Opus 9. Beethoven dedicated his next release, the three piano sonatas grouped as Opus 10, to the count’s wife, Anna Margarete von Browne, who besides being a benefactor may also have been one of his piano students.

The Piano Sonata No. 5 in C Minor (Op. 10, No. 1) comes from that early phase of Beethoven’s career when he was still internalizing the styles mastered by Mozart and Haydn, and yet the seeds of his radical future are already sown. In the wake of this sonata, composed between 1795 and 1797, Beethoven wrote two more landmark works in the same key, a string trio (Op. 9, No. 3) and another piano sonata, the Sonata Pathétique (Op. 13). These experimental compositions chafed against the pleasant stereotypes of salon music, and they established a tradition wherein Beethoven channeled his most inflamed passions into music in the key of C minor—most famously in the Fifth Symphony that came a decade later.

The tempo marking of this sonata’s first movement challenges its performer to play “very fast and with vigor,” and the dynamic markings, already bold from the outset in their forte and piano alternations, soon escalate to the more extreme contrast of fortissimo and pianissimo. After the aggressive arpeggios of the first theme, the contrasting music in E-flat major indulges in shapely melodies and fluid “Alberti bass” patterns in the left hand, a sound redolent of Mozart.

Within the “very slow” middle movement, songlike phrases dissipate or veer off path in stark and surprising ways. The music is understated and spacious, enriched by silences and simplifications where more notes would only have diluted the impact.

The finale shifts to the opposite extreme of tempo, calling for a breakneck Prestissimo tempo. It takes a bouncier, more playful approach to the C-minor tonality, but still it is uncompromising in its manipulation of the material. One cascading phrase bears a striking resemblance to a moment in the Fifth Symphony’s opening movement, both examples tumbling down the same unsettled sequence of diminished harmonies.

Aaron Grad ©2017

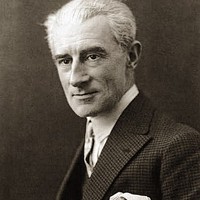

At the start of World War I, the 39-year-old Maurice Ravel volunteered as a truck and ambulance driver, forcing him to set aside Le tombeau de Couperin, a work-in-progress for solo piano honoring the French Baroque composer François Couperin. By the time Ravel finished the suite in 1917, it had acquired a more personal meaning, with each of the six movements dedicated to friends killed in the war.

Ravel transcribed four of the movements for chamber orchestra in 1919. Starting with the fluid melody of the Prélude, the oboe has an outsized role in the orchestration, echoing its prominence as a solo instrument in the Baroque era. Ravel dedicated this movement to Lieutenant Jacques Charlot (the godson of his music publisher), who died in battle in 1915.

The second movement, a Forlane, is based on a lively and flirtatious couple’s dance that entered the French court via northern Italy. Ravel sketched this movement before the war and subsequently dedicated it to the Basque painter Gabriel Deluc, who was killed in 1916.

The oboe returns to the fore in the Menuet, a French dance distinguished by its stately, three-beat pulse. Ravel dedicated this section to the memory of Jean Dreyfus, whose stepmother, Fernand Dreyfus, was one of Ravel’s closest confidantes during the war.

The Rigaudon pays tribute to two family friends of Ravel: Pierre and Pascal Gaudin, brothers killed by the same shell on their first day at the front in 1914. When faced with criticism that this unabashedly upbeat movement was too cheerful for a memorial, Ravel purportedly responded, “The dead are sad enough, in their eternal silence.”

Aaron Grad ©2018

Listen to Audio

Listen to Audio

Ludwig van Beethoven completed his fifth and final piano concerto during the miserable summer of 1809, when Napoleon’s army occupied Vienna for the second time in four years. By the time of the premiere two years later, Beethoven’s hearing had deteriorated so much that he could not perform the concerto himself. Having filled the void left by Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart’s death, Beethoven’s long run as the leading pianist-composer in Vienna had officially come to an end.

The Piano Concerto No. 5 is in many ways a sibling to the earlier “Eroica” Symphony No. 3, also in the key of E-flat. In the case of the concerto, Beethoven had no part in the nickname — “Emperor” came later from an English publisher — but both works share a monumental posture and a triumphant spirit.

To begin the concerto, the orchestra proclaims the home key with a single chord, and the piano leaps in with a virtuosic cadenza. The ensemble holds back its traditional exposition until the pianist completes three of these fanciful solo flights, the last connecting directly to the start of the movement’s primary theme. It is a remarkable structure for a concerto, with an assurance of victory, as it were, before the battle lines have been drawn.

The slow movement enters in the luminous and unexpected key of B-major with a simple theme, first stated as a chorale for muted strings. To bridge the distance back to the home key of E-flat, the finale pivots effortlessly on a single held note that relaxes down a half-step, setting up the piano’s propulsive entrance.

Aaron Grad ©2022

This concert is currently sold out. Sign up for the wait list above or click here to purchase tickets to the Happy Hour performance.

Please be aware that there will be heavier than normal traffic in downtown Saint Paul prior to our evening concert on SATURDAY, FEBRUARY 3 due to an event at the XCEL CENTER and events surrounding the SAINT PAUL WINTER CARNIVAL

Get driving directions and find nearby parking.

Find dining options close to the venue.

View seating charts to find out where you'll be seating.

SPCO concerts are made possible by audience contributions.

For exclusive discounts, behind-the-scenes info, and more:

Sign up for our email club!