Mahler’s Fourth Symphony

Sponsored By

- March 13, 2015

- March 13, 2015

- March 14, 2015

Sponsored By

Adams composed Son of Chamber Symphony fifteen years following his Chamber Symphony (to be performed on the SPCO concerts of March 14 and 15). As with the elder work, Junior is tautly scored: “It presents certain balance problems,” the composer has conceded, “because you have a trombone and a trumpet, and only one violin instead of sixteen. But I like that challenge. I like the challenge that the players feel, that each one is a soloist. It gives me an opportunity to do really interesting, virtuoso writing that I would never attempt with a large orchestra.” (Put another way, both chamber symphonies are damned hard to play.)

Adams hasn’t offered much in the way of explaining the work’s playful title. (“It came time to write another chamber symphony. Instead of calling it ‘Chamber Symphony No. 2,’” Adams said, “I figured I’d give it that name.”). The work serves also as the ballet score to Mark Morris’s Joyride, a more vividly descriptive title of the music’s kinetic energy—particularly in the first movement, whose buoyant, off-kilter rhythm starts quickly and becomes frenetic. This movement bears a strong filial resemblance to the Chamber Symphony’s more cartoonish moments. Son of Chamber Symphony’s second movement recalls Adams’s Naïve and Sentimental Music (1997) and Klinghoffer’s “Chorus of the Exiled Palestinians,” with its sinewy, lyrical melody in the winds supported by a pulsating accompaniment in the strings. But this music’s naïveté and sentimentality soon enough give way to bizarrerie. The caffeinated Presto finale alludes to the “News” aria from Nixon in China.

Patrick Castillo ©2014

American composer John Adams ranks among the most eminent musical voices of our time. A New England native displaced to the Bay Area, Adams became a vital force in that community’s contemporary music scene. In 1978 he assumed the role of new music advisor to the San Francisco Symphony, alongside then-music director Edo de Waart. Since that period, Adams has become especially known for his operas based on contemporary subjects, including Nixon in China (1987), Doctor Atomic (2005), and The Death of Klinghoffer (1991), whose political sensitivity has sparked protests throughout its performance history, most recently directed towards New York’s Metropolitan Opera in October 2014.

From 1988 to 1990, Adams served as Creative Chair of The Saint Paul Chamber Orchestra. His numerous honors include the Pulitzer Prize, Grawemeyer Award, and Musical America’s designation as Composer of the Year in 1997. — Patrick Castillo

The composer has provided the following note:

The Chamber Symphony, written between September and December of 1992, was commissioned by the Gerbode Foundation of San Francisco for the San Francisco Contemporary Chamber Players, who gave the American premiere on April 12. The Schoenberg Ensemble performed the official world premiere in The Hague, Holland, in January 1993.

Written for 15 instruments and lasting 22 minutes, the Chamber Symphony bears a suspicious resemblance to its eponymous predecessor, the Opus 9 of Arnold Schoenberg. The choice of instruments is roughly the same as Schoenberg’s, although mine includes parts for synthesizer, percussion (a trap set), trumpet, and trombone. However, whereas the Schoenberg symphony is in one uninterrupted structure, mine is broken into three discrete movements, “Mongrel Airs,” “Aria with Walking Bass,” and “Roadrunner.” The titles give a hint of the general ambience of the music.

I originally set out to write a children’s piece, and my intentions were to sample the voices of children and work them into a fabric of acoustic and electronic instruments. But before I began that project I had another one of those strange interludes that often lead to a new piece. This one involved a brief moment of what Melville called ‘the shock of recognition’: I was sitting in my studio, studying the score to Schoenberg's Chamber Symphony, and as I was doing so I became aware that my seven-year-old son, Sam, was in the adjacent room watching cartoons (good cartoons, old ones from the 1950s). The hyperactive, insistently aggressive and acrobatic scores for the cartoons mixed in my head with the Schoenberg music, itself hyperactive, acrobatic, and not a little aggressive, and I realized suddenly how much these two traditions had in common.

For a long time my music has been conceived for large forces and has involved broad brushstrokes on big canvasses. These works have been either symphonic or operatic, and even the ones for smaller forces, like Phrygian Gates, Shaker Loops, or Grand Pianola Music, have essentially been studies in the acoustical power of massed sonorities. Chamber music, with its inherently polyphonic and democratic sharing of roles, was always difficult for me to compose. But the Schoenberg symphony provided a key to unlock that door, and it did so by suggesting a format in which the weight and mass of a symphonic work could be married to the transparency and mobility of a chamber work. The tradition of American cartoon music—and I freely acknowledge that I am only one of a host of people scrambling to jump on that particular bandwagon—also suggested a further model for a music that was at once flamboyantly virtuosic and polyphonic. There were several other models from earlier in the century, most of which I came to know as a performer, which also served as suggestive: Milhaud’s La Creation du monde, Stravinsky’s Octet and L’Histoire du soldat, and Hindemith’s marvelous Kleine Kammermusik, a little known masterpiece for woodwind quintet that predates Ren and Stimpy by nearly sixty years.

Despite all the good humor, my Chamber Symphony turned out to be shockingly difficult to play. Unlike Phrygian Gates or Pianola, with their fundamentally diatonic palettes, this new piece, in what I suppose could be termed my post-Klinghoffer language, is linear and chromatic. Instruments are asked to negotiate unreasonably difficult passages and alarmingly fast tempi, often to the inexorable click of the trap set. But therein, I suppose, lies the perverse charm of the piece. (“Discipliner et Punire” was the original title of the first movement, before I decided on “Mongrel Airs” to honor a British critic who complained that my music lacked breeding.)

The Chamber Symphony is dedicated to Sam.

Patrick Castillo ©2014

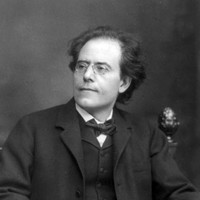

One of the mightiest musical voices of the late Romantic period is that of the Austrian composer and conductor Gustav Mahler. Mahler’s epic cycle of nine symphonies stands among the most powerful and intensely personal statements in the Western canon. In addition to his symphonies, Mahler left a significant catalogue of vocal pieces, many with orchestra, which likewise rank among the definitive works of the turn of the twentieth century. With each of his colossal symphonies and song cycles, Mahler created a vast musical world, into which he poured heartrending expressions of profound joy and sorrow, love and fear, wonder and anxiety at the world around him, and deep reflections on the human condition, in turns fatalistic and sublime.

Mahler’s Fourth Symphony, completed in 1900, presents something of an anomaly among the composer’s other symphonies. Especially in contrast to the unrelenting Second Symphony and the sprawling Third, whose massive opening movement alone outlasts any of Mozart’s symphonies in their entirety, Mahler’s Fourth is limpid and compact. Its character, too, surprised listeners of Mahler’s time: having stunned audiences with the expressive enormity of his first three symphonies, Mahler now turned to an almost childlike naïveté with the Fourth. “It is basically different from my other symphonies,” he admitted. “But it must be that way; it would be impossible for me to repeat myself, and just as life moves on, I likewise explore new paths in every new work.” To his wife, Alma, the composer added, “My Fourth will be very strange to you. It is all humorous, ‘naïve,’ etc.; it represents the part of my life that is still the hardest for you to accept and which in the future only extremely few will comprehend.”

While work on the symphony proper took place between 1899 and 1900, the Fourth took for its finale a song composed in 1892: “Das himmlische Leben” (“The Heavenly Life”), whose text comes from the collection of German folk poetry Des Knaben Wunderhorn. Motifs from this song run throughout the Symphony’s preceding three movements, thus prefacing the work’s conclusive statement—a vision of heaven—with prefigurations of that vision. Mahler: “It contains the cheerfulness of a higher and, to us, an unfamiliar world that holds for us something eerie and horrifying. In the final movement, although already belonging to this higher world, the child explains to us how everything is meant to be.”

Patrick Castillo ©2014

Due to a scheduling conflict, Fanfare will NOT take place before the concert on Saturday, March 14.

Have questions about the new Ordway Concert Hall? Visit thespco.org/concerthall for information about our new downtown Saint Paul home.

ROCK THE ORDWAY this March with an unprecedented mix of eclectic artists and performances specifically chosen to shake things up while also showcasing the state-of-the-art acoustics and intimacy of the new Concert Hall. Whether you’re into classical, R&B, opera, show tunes, Latin-fusion, love songs, the sounds of South Africa or choral music, please help us open the doors, raise the roof and celebrate Minnesota’s newest world-class performance hall. Learn more at ordway.org/rocktheordway

Get driving directions and find nearby parking.

Find dining options close to the venue.

View seating charts to find out where you'll be seating.

Get driving directions and find nearby parking.

Find dining options close to the venue.

View seating charts to find out where you'll be seating.