Mozart, Schubert and Rameau

Sponsored By

- March 18, 2016

Sponsored By

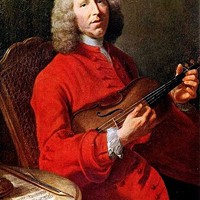

Before Jean-Philippe Rameau moved to Paris in 1722, he worked as a church organist in various small towns, and his only notable compositions were assorted vocal works and a book of harpsichord pieces. He soon published a groundbreaking harmony treatise and two more books of keyboard suites, paving the way for his greatest ambition, finally achieved at the age of fifty: to compose grand operas. He went on to create some thirty works for the stage, the finest by any French composer since Jean-Baptiste Lully.

Les Boréades was Rameau’s last tragic opera, and it was still unperformed when he died a year after its completion. Before the first scene opens on a woodland hunt, the Ouverture establishes the setting, including calls that evoke hunting horns. The gusty bursts of violin scales portray the winds, which become a significant plot point in the opera.

It was a longstanding French custom to incorporate dance numbers within operas, which explains the presence in this suite of two examples of contredanse, the French adaptation of the British “country dance” in which partners form parallel lines. The main theme of the Contredanse en rondeau leans uncharacteristically on a foreign pitch, A-natural, which rubs against the home key of C-minor. In the next selection, an independent bassoon line, acting as a foil to the violin melody, adds a special depth and richness to the spellbinding entrance music for the muse Polymnie. For the final pairing of “very lively” contredanses from Act V, a contrasting episode in the minor key interrupts the outer statements of a foot-stomping main theme in the major key.

Aaron Grad ©2025

Listen to Audio

Listen to Audio

After a dazzling childhood spent touring the great cities of Europe as a prodigy, Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart ended up spending his early adulthood stuck in his hometown of Salzburg, working a stifling church job alongside his overbearing father and hustling for side gigs entertaining the town’s upper crust. His luck finally turned at the age of 24, when prospects he had cultivated years earlier led to an invitation to compose an opera for the royal court in Munich. With one foot already out the door, Mozart wrote his last symphony in Salzburg at the end of August and led its first performance there a few days later.

This Symphony in C Major — Mozart’s 34th out of a lifetime total of 41 — shows how comfortable the young composer was personalizing a style he modeled after the seminal symphonies of Joseph Haydn (whose brother happened to work in Salzburg too). Symphonies were born out of the Italian opera overture, or sinfonia as it’s called in Italian, and the consummate showman Mozart leans into that overture style in the fast first movement that skips the usual repeat and instead amps up the drama in the exploratory development section and extended coda.

One curiosity about this symphony is that Mozart started writing a minuet after the first movement, which we know from 14 crossed-out measures that appear on the back of the page where the first movement ends. He may have even written the whole movement, since the next two pages of the manuscript are ripped out, but he decided to make this a three-movement symphony — still a common form at the time — and so it instead proceeds to the tuneful style of Andante that was a signature of Mozart’s slow movements. This one strolls at a slightly faster tempo than others, based on an adjustment to the tempo he added later. The scampering finale shows off Mozart’s expansive sense of orchestral color, with woodwinds that take on more independent roles (especially the oboes) and layers of contrapuntal activity spreading the action among different instrument groups and pitches ranges.

Aaron Grad ©2025

Get driving directions and find nearby parking.

Find dining options close to the venue.

View seating charts to find out where you'll be seating.

Get driving directions and find nearby parking.

Find dining options close to the venue.

View seating charts to find out where you'll be seating.