Mozart’s Serenade for Winds No. 12

After Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart moved to Vienna in 1781 to try his luck as a freelancer, he was eager to catch the ear of Emperor Joseph II and those in his court. One trend Mozart picked up on was the interest in harmoniemusik, or music for small wind ensembles. The emperor had recently added a harmonie to his retinue, the kind of band that was perfect for entertaining at outdoor gatherings, where its sound carried well on the open air. Mozart composed two serenades for just such a group while he was still new to Vienna, one in the key of E-flat Major, and another in C Minor.

We know that Mozart created the E-flat Serenade to try to impress the emperor’s musical advisor, but for the C-minor Serenade (K. 388) that came next, no record of its origin has survived. No matter the setting, it is hard to imagine any reaction to this music other than shock, considering the type of pleasant and forgettable music usually played by those wind ensembles.

The Serenade begins at full force, climbing up an arpeggio in C-minor and then dropping precipitously to a pungent dissonance. Several pregnant pauses heighten the movement’s sense of drama, especially at the return to the main theme for the recapitulation.

The Andante second movement takes up the gentle key of E-flat major, and the first theme is delivered in a piano dolce (soft and sweet) tone by just clarinets and bassoons. The oboe and clarinet trade melodies that argue each instrument’s claim to be the truest surrogate for the human voice — especially in the hands of Mozart, who was always an opera composer at heart — while a few choice phrases led by the horns add a darker contrasting hue.

In those first years in Vienna, Mozart became fascinated by Baroque counterpoint as mastered by Johann Sebastian Bach and George Frideric Handel. The entire Serenade is full of contrapuntal layering, but it becomes most explicit in the third movement, a Minuet constructed as a canon in which the voices follow each other at a fixed distance. To compound the contrapuntal wonder, the contrasting trio section weaves a canon in contrary motion, meaning that upward motion in one voice corresponds to the equivalent downward motion in the next voice, and vice versa.

The finale unfolds as a theme and variations, building from a C-minor melody first voiced by the oboes and bassoons. The coda finally settles on C-major, but it hardly softens the intense effect of this unflinching serenade.

Aaron Grad ©2022

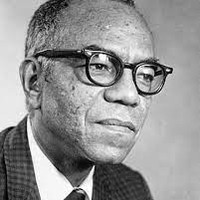

The nephew of jazz pioneer King Oliver, Ulysses Kay took up the piano, violin and saxophone as a child, and he ended up studying composition at the Eastman School, Yale University and Columbia University (with a break in there for a stint playing in a Navy band during World War II). The Rome Prize and other fellowships allowed Kay to live in Italy from 1949 to 1953, until he came back to New York to take a job with BMI, the composer’s rights organization. It was through that job that he met John Solum, a flutist based in New York who was at the start of a major recital and concerto career; Kay offered to write something for flute, and Solum came back with a commission for a score featuring flute and a small orchestra.

Kay named Aulos after an early wind instrument that dates back at least 7,000 years, and which was a favorite of the Ancient Greeks. With alluring moments of improvisatory freedom and an atmospheric orchestration for two horns, percussion and strings, Aulos was an attractive vehicle for a flute soloist, and Solum was determined to help circulate it. (In a letter to Kay archived at Columbia University, Solum pondered how best to approach leading conductors of the day: Eugene Ormandy, Leopold Stokowski, George Szell, Erich Leinsdorf, etc.) Kay did finally gain a teaching post, spending the last part of his career on the faculty of Lehman College, but his attractive, musician-friendly music is still waiting for the wide dispersal it deserves.

Aaron Grad ©2022

Benjamin Britten had a precocious start in music, studying piano and viola and composing hundreds of works by the time he was a teenager. At fourteen, Britten’s viola teacher introduced him to the composer Frank Bridge, who agreed to give Britten private lessons. “I, who thought I was already on the verge of immortality, saw my illusions shattered,” Britten later wrote about his course of study with Bridge, a demanding teacher who fostered the rigorous technique needed to round out Britten’s natural inventiveness.

Bridge’s name mostly arises now thanks to the tribute composed by his pupil in 1937. Britten accepted the commission on very short notice from the Boyd Neel Orchestra, which desperately needed a new English piece to play at the prestigious Salzburg Festival. The orchestra had already performed Britten’s Simple Symphony for Strings, making the young composer a natural choice. Britten obliged by writing the Variations on a Theme of Frank Bridge in less than a month.

The source material, taken from Bridge’s Three Idylls for string quartet from 1906, is just the slightest wisp of a melody, which Britten expanded into a set of free variations. Coming out of the dramatic introduction, a chord sustained under a series of plucks reveals itself as the start of the theme. Each brief variation highlights a particular aspect of Bridge’s personality, as outlined by Britten: the Adagio corresponds to “his depth,” the March “his energy,” and the Romance “his charm.” The next three movements drift toward parody, with a Gioachino Rossini-inspired Aria Italiana (“his humor”), a neo-Baroque Bourrée classique with prominent violin solos (“his tradition”), and an irreverent Viennese Waltz (“his enthusiasm”). A fiery Perpetual Motion (“his vitality”) clears the air for the haunting Funeral March (“his sympathy”) and the ethereal Chant (“his reverence”). The work closes with a Fugue and Finale, a testament to Bridge’s “skill and dedication.”

Aaron Grad ©2022

All audience members and staff will be required to wear non-cloth masks (N95, KN95, KF94 or surgical masks). Proof of vaccination, booster or a negative COVID-19 test result will no longer be required. More Information

Concerts are currently limited to 50% capacity to allow for distancing. Tickets are available by price scale, and specific seats will be assigned and delivered a couple of weeks prior to each concert — including Print At Home tickets. Please email us at tickets@spcomail.org if you have any seating preferences or accessibility needs. Seating and price scale charts can be found at thespco.org/venues.

Get driving directions and find nearby parking.

Find dining options close to the venue.

View seating charts to find out where you'll be seating.

Get driving directions and find nearby parking.

Find dining options close to the venue.

View seating charts to find out where you'll be seating.