Postcards Across the Atlantic

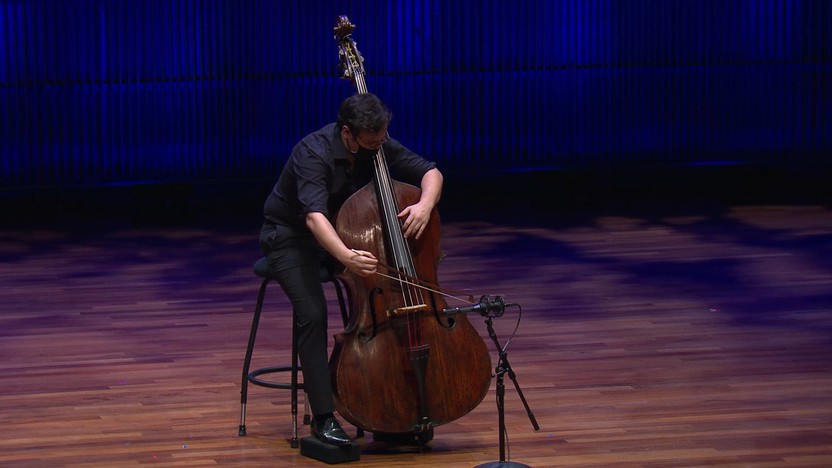

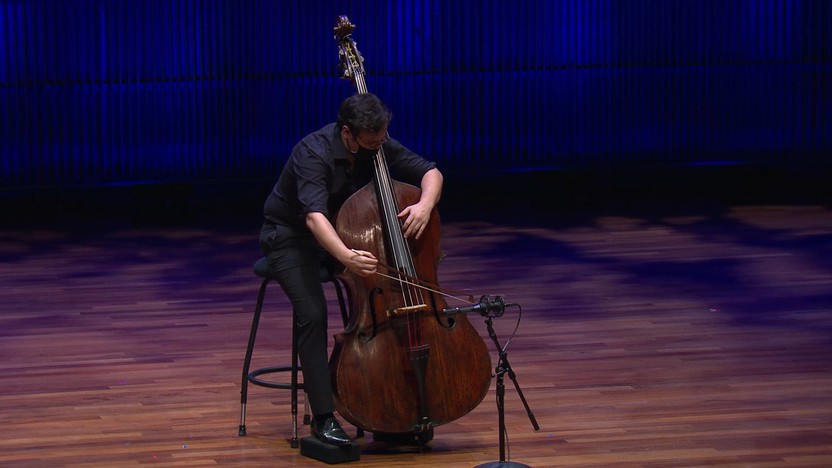

Although J.S. Bach was receptive of Italian innovations — as evidenced in the composer’s various concertos, whose three-movement form, buoyant ritornello themes and lively figuration derive from Antonio Vivaldi’s example — he also remained deeply immersed in the elaborate contrapuntal forms that the Italian composers had largely abandoned. Bach’s almost mystical devotion to that ideal produced some of his most impressive achievements. These include the compendium of fugal counterpoint embodied in The Well-Tempered Clavier, The Musical Offering and The Art of the Fugue; the great passacaglias, fugues and other contrapuntal works for organ; and in some ways most remarkably, in the Chaconne in D Minor from the Partita for Solo Violin, BWV 1004.

This last work is one of a half dozen that Bach composed for solo violin: three sonatas and an equal number of partitas. The composer wrote out a fair copy of these six pieces, which he evidently considered a unified set, in 1720, but they were not published during his lifetime. His motivation for creating this music remains unknown. Bach was a capable violinist, but the violin writing in these works suggests that he fashioned them with a virtuoso performer in mind.

The term “partita” is synonymous with dance suite. Like other composers of the Baroque era, Bach used popular dance forms of his day as vehicles for sophisticated musical invention, preserving the typical rhythms and characters of his sources but imparting to them artful melodic, harmonic and contrapuntal details. What is extraordinary about his solo violin partitas is that they convey through the voice of a single melody instrument not only rhythms and melodic ideas appropriate to the traditional dance forms but harmonic nuances as well. Exploiting the entire range of the instrument and judiciously using multiple stops to add harmonic shading to the melodic lines, Bach created music that is surprisingly rich and complete. J.N. Forkel, the composer’s early biographer, remarked of this achievement: “He [Bach] has so combined in a single part all the notes required . . . that a second part is neither desired nor possible.”

The Partita in D Minor, BWV 1004, concludes with a type of movement frequently placed at the end of dance suites during the 17th and early 18th centuries. The chaconne probably originated as a Spanish dance, but during the Baroque era it became for composers a particular procedure of contrapuntal variation. Typically, the chaconne entails a short, recurring bass-line melody implying a certain sequence of harmonies. As this figure courses through a continuous circle of repetitions, counter-melodies and other developments play over and around it in counterpoint. The challenge to the composer is to invent diverse and interesting variations within the narrow framework imposed by the repetitive phrase structure.

In the present work, Bach meets that challenge superbly. Using the restrictive chaconne procedure as a foil to his imagination, the composer spins a series of counter-melodies against the harmonic progression whose recurrences underlie the work. Moreover, he shapes the resulting discourse into a coherent large-scale form. That form includes three broad sections, the central part turning to the major mode to relieve the stern D-minor harmonies of the opening and closing paragraphs. Within these sections the music acquires further shape, as accelerating figuration and increasingly charged rhetoric build periodically to strong climaxes. Bach employs a veritable encyclopedia of violin technique, from multiple stops (the playing of two or more notes simultaneously on different strings) and rapid changes of register to running passagework, varied articulation and agile bowing. But while the melodic invention is breathtaking, it remains anchored to a rigorous formal process. The germinal theme over which the linear details unfold provides both a steady pattern of four-measure phrases and a series of austere but expressive harmonies repeating over the course of the piece. Together, these elements give the music a sense of inexorable progression.

— © Paul Schiavo

Paul Schiavo ©1997

the river has its destination is a meditation piece. Through timbre, pitch and negative space, this composition should be used by the performer as a tool to meditate. The playing of the notes happens when exhaling. The piece is a journey through four stages of meditation. The first stage is an entrance or preparation for the meditation. The second stage is the observation of breath. The third stage is the observation of the body as it goes toward transcendence. The fourth stage is transcendence.

— © Ambrose Akinmusire

Ambrose Akinmusire ©2020

After centuries of stagnation, homegrown British music flourished in the early 1900s, thanks to innovative compositions by the likes of Elgar, Vaughan Williams and Holst. William Walton was among the first generation of musicians to grow up on a diet of new British music, starting with his childhood training as a chorister at Christ Church Cathedral in Oxford, and continuing from the age of 16 as a student at Oxford University. During a truncated course of study that ended after multiple failures to pass a required exam, Walton spent much of his time poring over foreign scores in the library, gleaning new ideas from composers Stravinsky, Ravel, Bartók and Schoenberg’s Viennese cohort. A string quartet born during Walton’s student years debuted to much fanfare at an international festival, and it exemplified his youthful pushback against conservative British norms. Not surprisingly, England’s critics panned it, while Schoenberg’s disciple composer Alban Berg heaped praise on it.

Walton withdrew that fledgling quartet, and he found his first real success with the jazz-laced Façade and a Viola Concerto that is still a pillar of the repertoire. His orchestral works earned him a sterling reputation at home and abroad, and his early embrace of film scoring (starting in 1934) brought his sound to even wider audiences. Chamber music was absent from his working life for more than twenty years, until Walton finally began a new quartet in 1945. It took him nearly two years to complete the String Quartet in A Minor.

With its modal phrases and austere counterpoint, Walton’s mature quartet attests to his lasting debt to Ravel and Bartók, whose efforts set the standard for quartets in the early twentieth century. In the taut first movement, a fugal episode also confirms Walton’s link to the more distant past, recalling the way Beethoven and other Classical masters used the controlled chaos of formal polyphony to raise the emotional temperature. For the inner movements, a brisk and pointed Scherzo balances against a muted Lento, its dark hues tinted with traces of church music and the pastoral innocence of mainline British music.

The aggressive finale again channels Beethoven and his stabbing, obsessive approach to short gestures. In that regard, it resembles the quartet finale that the esteemed Elgar wrote (in the same Allegro molto tempo) near the end of his life. By the time he wrote his own quartet, Walton was an elder statesman himself, and his integration of British sensibilities with modern European trends had already helped to reshape his country’s musical future.

— © Aaron Grad

Aaron Grad ©2020

Get driving directions and find nearby parking.

Find dining options close to the venue.

View seating charts to find out where you'll be seating.

SPCO concerts are made possible by audience contributions.

For exclusive discounts, behind-the-scenes info, and more:

Sign up for our email club!