Alicia McQuerrey Plays Vivaldi’s Flute Concerto, La Notte

Antonio Vivaldi came of age during a glorious boom in violin construction and technique around northern Italy, including his native Venice, where his own father was a professional violinist. With a job there teaching violin at a school for orphaned girls, Vivaldi was able to use his talented students to test out his compositions, especially the many concertos — more than 500 by the end of his life — that built on advances made by local peers over the past several decades. Vivaldi developed or codified some of the most important aspects of concerto style, such as the fast-slow-fast sequence of movements and the use of ritornello structure as a way to differentiate sections for the soloist and full ensemble.

Vivaldi only released his first solo concertos for the transverse flute in 1728, when his shrewd publisher noticed a growing fad for the instrument and requested works he could sell. This version of the flute, held horizontally like a modern flute, gradually displaced its up-and-down relative, what we now call the recorder. For the Flute Concerto in Minor, Vivaldi recycled music from an earlier chamber concerto for flute, two violins and bassoon, a work likewise known by the nickname “La notte” or “The Night.” The six linked sections contain some of Vivaldi’s most colorful scene painting, starting with a Largo opening that makes the most of the flutes long tones and fluttering trills, followed by a bewitching section subtitled “The Ghosts.” Another slow-fast sequence shows the flute to be a melodious and agile leading voice. The final Largo section, with the apt subtitle of “Sleep,” is muted and exceedingly still, and then one last fast section is filled with the type of churning rhythms and thrilling dialogue that have allowed Vivaldi’s seminal concertos to stand the test of time.

Aaron Grad ©2021

Eleanor Alberga began playing piano as a five-year-old in her native Jamaica, and by ten she was writing her own piano pieces. She went on to earn a scholarship that allowed her to study at the Royal Academy of Music in London, and she has been based in England ever since. For much of her career she balanced composing with extensive work as a concert pianist, but with a spate of high-profile commissions (including a 2015 concert opener for the BBC Proms), Alberga has shifted her focus entirely to composing more of the vocal, orchestral and chamber music that has made her one of the most respected composers in the United Kingdom and beyond. She wrote the following description of Succubus Moon, composed for the City of London Festival in 2007 and featured on a recent album dedicated to Alberga’s music on Navona Records.

“The romantic and the demonic lie side by side in this work. Over centuries, man has interpreted his fear of the dark and unknown as caused by beings and superstitions outside himself; one of these interpretations became Incubi and Succubi, evil presences doing harm to humans. The piece juxtaposes the ethereal, tranquil, and reflective moon against the impenetrable darkness of the night where the demonic and seductive Succubus reigns. The oboe is the main protagonist, leading the mood or taking over what the strings have set up. The strings have their own episodes, and sometimes join with the oboe in main material.

“The music goes from sparse to more driven rhythmic sections, to dreamy moonstruck moments, and finally drifts away. Towards the end there is, unusually, a C-major chord — a ray of hope as the moon shines out amidst the primal terror.”

— Eleanor Alberga

Aaron Grad ©2021

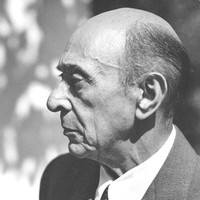

Before Arnold Schoenberg became the teacher and trendsetter at the center of the “Second Viennese School” of composers who explored the wilds of atonality, he was a self-taught amateur steeped in the luxurious Romanticism of Franz Liszt and Richard Strauss. The closest he came to having a composition teacher was through his friendship with Alexander von Zemlinsky, and it was during their vacation together in 1899 that Transfigured Night emerged from three swift weeks of work.

Schoenberg’s great innovation in Transfigured Night was to apply the idea of program music, as found in the tone poems of Liszt and Strauss, to a chamber ensemble. Schoenberg’s original scoring for two violins, two violas and two cellos matched a format pioneered by Johannes Brahms, in whose hands the string sextet became a vehicle for pure chamber music with a Classical orientation. Instead of the usual abstract movements, Schoenberg created one continuous score in five sections, following the shape of the poem "Verklärte Nacht (Transfigured Night)" by Richard Dehmel, about a forlorn couple that, while walking on a moonlit night, works through the revelation that her pregnancy resulted from an affair.

The musical storytelling relies on the skillful manipulation of tonal harmony over the course of one long journey from minor to major. Supported by a nervous drone, the first section sets the course by plodding down the minor scale in lopsided, dotted rhythms. This stepping pattern becomes a familiar point of reference, returning in different forms to remind us of the couple and their fateful walk together.

The second section, beginning with an unexpected major chord, corresponds to the second stanza of the poem, in which the woman “confesses a sin to the man at her side: she is with child and he is not its father.” The music becomes agitated, smeared with rising chromatics, until the third section intervenes with music of a simpler and more somber character, linked to the section of the poem in which “she staggers onward.”

The third section ends on a minor chord, setting up the crucial moment: With a decisive pivot to a major chord, a cello melody gives voice to the man’s wish that his companion should “not burden her soul with thoughts of guilt.” A lustrous violin solo brightens the night, just as “the moon’s sheen enwraps the universe.”

The final section forms a tranquil coda in D major, basking in love’s warmth that “will transfigure the little stranger.” The stepping theme returns with new optimism, and shimmering arpeggios offer a parting view of “wondrous moonlight.”

Aaron Grad ©2021

All audience members are required to present proof of full COVID-19 vaccination or a negative COVID-19 test within 72 hours prior to attending this event. Masks are required regardless of vaccination status. More Information

Concerts are currently limited to 50% capacity to allow for distancing. Please email us at tickets@spcomail.org if you have any accessibility needs.