EXPRESS CONCERT: Cassie Pilgrim Plays Bach’s Oboe d’Amore Concerto

Note: selections from this work will be performed at two different intervals during the program, with the last three movements performed before Bach's Sarabande from Cello Suite No. 5.

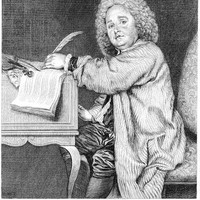

Jean-Féry Rebel, the son of a musician in the court of Louis XIV, had the privilege of studying violin and composition with Jean-Baptiste Lully, the king’s favorite composer. Rebel was 71 and retired from his long career composing and performing dance music when he wrote his final and most consequential work, The Elements. The bulk of this “symphonie nouvelle” consisted of orchestral dances, infusing the French ballet style mastered by Lully with aspects of Italian sinfonias (i.e. opera overtures, which evolved into symphonies as we know them).

Musical details of The Elements correspond to those Classical “elements” that comprise the natural world: The low strings represent Earth, the bright tone of piccolo evokes Air, violins correspond to Fire, and the mellow flutes voice the sound of Water. This highly colorful and varied suite also offers images of nightingales, hunters giving chase, lively dances in assorted styles, and a song for Love.

For all the novelty within the suite, the highlight of The Elements is the very first chord of its jaw-dropping introduction, titled Chaos. Rebel felt compelled to explain his thinking in a forward to the published score: “The introduction to this work is Chaos itself; that confusion which reigned among the Elements before the moment when, subject to immutable laws, they assumed their prescribed places within the natural order. This initial idea led me somewhat further. I have dared to link the idea of the confusion of the Elements with that of confusion in Harmony. I have risked opening with all the notes sounding together, or rather, all the notes in an octave played as a single sound.”

Aaron Grad ©2025

Caroline Shaw is one of the most celebrated composers alive today, but even after becoming the youngest recipient of the Pulitzer Prize for Music in 2013 (not to mention the winner of five Grammy Awards and counting), she still identifies herself simply as a musician — a term that encompasses her expansive work as a violinist, singer, improviser and producer. She began studying violin at the age of two with her mother, a Suzuki teacher, and she formed her own string quartet while growing up in Greenville, North Carolina. Still, she waited until 2009 to compose the first in what has become a groundbreaking series of quartets. The Attacca Quartet recorded six of those works, including Entr’acte from 2011, on an album that won the 2020 Grammy for Best Chamber Music/Small Ensemble Performance.

Shaw was inspired to create Entr’acte (a theater term for music that separates two acts) after hearing a string quartet by Joseph Haydn. What she wrote about Haydn could just as easily be applied her own imaginative sound effects and extended techniques: “I love the way some music suddenly takes you to the other side of Alice’s looking glass, in a kind of absurd, subtle, Technicolor transition.” Her own score, she wrote, “is structured like a minuet and trio, riffing on that classical form but taking it a little further.”

Aaron Grad ©2025

The self-taught composer Kazuo Fukushima got his start in the same experimental workshop in the early 1950s that helped launch his peer Toru Takemitsu. As Japanese composers were navigating for the first time how to bring their country’s traditional art forms into the sphere of Western art music, Fukushima found that parallel flute traditions could be a particularly fruitful area of overlap, and his early flute works earned him such influential admirers as Stravinsky and the Italian flute star Severino Gazzelloni, who commissioned Mei. With its free-floating time and fluid sense of pitch created by bends that elide from one tone to the next, this score echoes the sound of the Japanese Nohkan, a transverse flute (i.e. held sideways, like a modern flute) that was a fixture of traditional Noh theater dating back to the fifteenth century. Fukushima titled the work after a Chinese character that “signifies the dark, dim, intangible.”

Aaron Grad ©2025

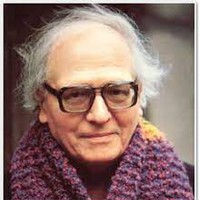

The composer Olivier Messiaen was serving in the French military in 1940 when he was captured during the Nazi invasion. He was transferred to a prisoner-of-war camp in Poland known as Stalag VIIIA, where among his fellow inmates he found accomplished musicians who played violin, clarinet and cello. With the help of a sympathetic guard, Messiaen obtained paper, a pencil and a quiet space in which to compose, and he even convinced his captors to bring in an upright piano so that he could perform with his colleagues. On January 15, 1941, the motley quartet performed Messiaen’s newest work for a rapt audience of prisoners and guards alike in a frigid, unheated barrack.

The work first heard on that extraordinary day was Quatuor pour la fin du temps, or Quartet for the End of Time. The title came from a passage in Chapter 10 of the Book of Revelation, in which a “mighty angel … cried in a loud voice … that there should be time no longer.” Messiaen was a devoted Catholic, and music was a prime vehicle for his faith and mystical worldview. He was also a birdsong collector, a student of the modes and rhythms of Eastern music, a synesthete (meaning that his brain mingled sensory inputs of sound and color), and a composer and organist with the finest training from the Paris Conservatory — all of which can be heard and felt in Quartet for the End of Time.

The quartet consists of eight disparate yet interrelated movements. In a preface to the published score, Messiaen gave a detailed account of each movement, including Abyss of the Birds for solo clarinet. “The abyss is Time with its sadness, its weariness,” Messiaen wrote. “The birds are the opposite to Time; they are our desire for light, for stars, for rainbows, and for jubilant songs.”

Aaron Grad ©2025

Luckily for Johann Sebastian Bach, his illustrious peer Georg Philipp Telemann had just recently accepted the top church job in Hamburg when another plum position opened up in Leipzig in 1723. Bach was able to secure the position of Thomaskantor, a demanding role that entailed both directing music for the principal churches of Leipzig and training the young choristers under his care. Somehow he also found time to let off steam directing the amateur musicians who participated in the Collegium Musicum. To fill out the performances they gave in a local coffee house, Bach dipped into his catalog of instrumental works he had amassed during earlier periods in Weimar and Cöthen, where he had more opportunities to make music outside of the church. And since he had an abundance of keyboard virtuosos available in the ensemble—namely his own sons — Bach took it upon himself to rework old concertos he had written for oboe or violin and turn them into the first concertos ever designed to feature harpsichord.

The original source of this concerto is lost, but musicologists have surmised that it might have been written for oboe d’amore, a sibling of the oboe that is pitched slightly lower and has a distinctively sweet and mellow tone, as developed by instrument makers in Leipzig in the 1710s. Following the influential model of solo concertos popularized by Vivaldi, the first movement revolves around a recurring ritornello theme. The ability of the oboe d’amore to sustain and shape luxuriously long notes and phrases proves to be especially valuable in the central Larghetto that moves to the related key of F-sharp minor. The finale has a dance-like lilt to its three-beat meter, injecting a bit of the flavor of a French dance suite into the Italian concerto template.

Aaron Grad ©2025

Johann Sebastian Bach served as Kapellmeister to Prince Leopold of Cöthen from 1717 to 1723. Working in a secular position for a musically inclined patron, Bach concentrated more on instrumental music than at any other point in his career, and he produced such landmark works as the Brandenburg Concertos, the Sonatas and Partitas for solo violin, and the first book of the Well-Tempered Clavier. Bach probably composed his Six Cello Suites in Cöthen as well, likely before the solo violin set from 1720. Bach’s own manuscript has been lost, so the few reliable sources for the suites are surviving copies made during Bach’s life, including one in the hand of his second wife, Anna Magdalena.

The Fifth Suite calls for a distinctive tuning, with the high A-string lowered one step to G. Modern cellists sometimes maintain a standard tuning, but either way Bach’s plan influences the shapes of the chords and melodies. The fourth movement, a Sarabande, is a deeply haunting marvel of understatement: The two sections comprise just eight and twelve measures respectively, only one note sounds at a time throughout, and the rhythms never deviate from eighth- and quarter-notes.

Aaron Grad ©2025

Our Express Concerts are 60-75 minutes of music without intermission. Learn more at thespco.org/express.

Get driving directions and find nearby parking.

Find dining options close to the venue.

View seating charts to find out where you'll be seating.

Get driving directions and find nearby parking.

Find dining options close to the venue.

View seating charts to find out where you'll be seating.