Elgar’s Serenade for Strings

For 200 years following Henry Purcell’s death in 1695, the most significant music created in England was the work of foreigners, including George Frideric Handel, Johann Christian Bach and Franz Joseph Haydn. The man who broke England’s dry spell was an unlikely candidate — the son of a piano tuner, Catholic in a Protestant country, and untrained in music except for some violin lessons as a teenager. Edward Elgar gained international recognition with his intriguing Enigma Variations in 1899, and he helped forge a distinctly British sound in the waning years of the Romantic era.

That signature score that made Elgar famous in his forties was built off of the hard work of his journeyman years, including a period when he supported his family by teaching and conducting in Malvern, a sleepy spa town. It was there that Elgar composed his Serenade for Strings in E Minor in 1892, incorporating some material from an earlier work he had abandoned. The Serenade title evoked those quintessential pieces of night music that Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart wrote to entertain his Austrian patrons, and the genre retained its emphasis on breezy pleasure even as it morphed from glorified background music for outdoor parties to a staple of the nineteenth-century concert hall with sterling examples by Antonín Dvořák and Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky. Given his career profile at the time, Elgar had to settle for a modest debut for his Serenade when he conducted a private reading by his students in the Worcester Ladies’ Orchestral Class.

A nimble rhythmic figure ushers in the dance-like first movement, set in a flowing meter that maintains its thrumming pulse under a series of elegant melodies. After a central Larghetto movement featuring one of Elgar’s most tender melodies, the finale rounds out this slim Serenade with more dancing music, including a closing reference to the first movement’s bouncing rhythm.

Aaron Grad ©2021

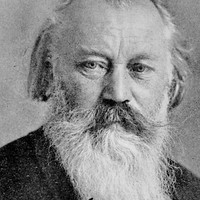

After the death of his mentor and champion Robert Schumann in 1856, Johannes Brahms did not publish any music for the next four years, and he performed only sporadically at the piano. While supporting himself by teaching and conducting, he labored over a Piano Concerto, studied counterpoint and other musical styles of the past, and challenged himself to experiment in new forms. Each year from 1857 to 1859, he spent a few months conducting a choir and offering piano lessons in Detmold, Germany, and it was there that he wrote two Serenades, using as his guide the Classical-era tradition of lighthearted music for evening gatherings. The Serenade No. 1 in D Major (1857–58) existed in a version for nine players, until Brahms expanded the scoring to chamber orchestra in 1860. The Serenade No. 2 in A Major (1858–59) also used less than a full orchestral complement, omitting violins.

The Serenades were important laboratories for Brahms. Free of the gravitas of symphonies (a form that stymied him for decades) but extending beyond the small-scale comfort zone of solo piano music and songs (genres that dominated his early output), these fruitful trials in large-ensemble writing brought forward the full potential that Schumann had seen years earlier.

Brahms almost titled the First Serenade a “Symphony-Serenade,” and without the twin scherzos inserted after the first movement and before the last, the remaining four movements do resemble the structure of a symphony. The droning start of the Allegro molto movement is unabashedly pastoral, and then the first Scherzo counters with a more urban atmosphere, combining unsettled unison lines and chains of drifting harmonies with elegant, dance-like music. The stately dotted rhythms (alternating long and short notes) of the unhurried slow movement reinforce the link to music of the past, as does the Minuet pairing with its contrast between major and minor keys. The second Scherzo returns to the sound of horn calls and rustic harmonies, setting up the Finale and its spirited new take on those lopsided dotted rhythms. This reconstruction of Brahms’ lost nonet version (completed in 1988 by Alan Boustead) brings out the individuality and intimacy of the music, in the spirit of the fun-loving serenades of yesteryear.

Aaron Grad ©2021

All audience members are required to present proof of full COVID-19 vaccination or a negative COVID-19 test within 72 hours prior to attending this event. Masks are required regardless of vaccination status. More Information

Concerts are currently limited to 50% capacity to allow for distancing. Tickets are available by price scale, and specific seats will be assigned and delivered a couple of weeks prior to each concert — including Print At Home tickets. Please email us at tickets@spcomail.org if you have any seating preferences or accessibility needs. Seating and price scale charts for the Ordway Concert Hall can be found at thespco.org/venues.

Get driving directions and find nearby parking.

Find dining options close to the venue.

View seating charts to find out where you'll be seating.

SPCO concerts are made possible by audience contributions.

For exclusive discounts, behind-the-scenes info, and more:

Sign up for our email club!